Not only were issuers having to pay elevated new issue premiums in late 2018, in many cases the spread widening in the secondary market made for tricky calculations, leaving some trades undersubscribed.

“Concessions have been higher in euros than dollars recently, but it’s not only that — in dollars you have known what the concession will be, whereas euros has needed some careful assessment,” says Lee Cumbes, head of SSA DCM at Barclays in London.

The picture is muddied further by the fact that it appears to be one rule for some issuers and a different one for others — particularly those from Germany, which have been able to garner larger order books for trades when others offering the same concession in the same maturity yielded poorer results.

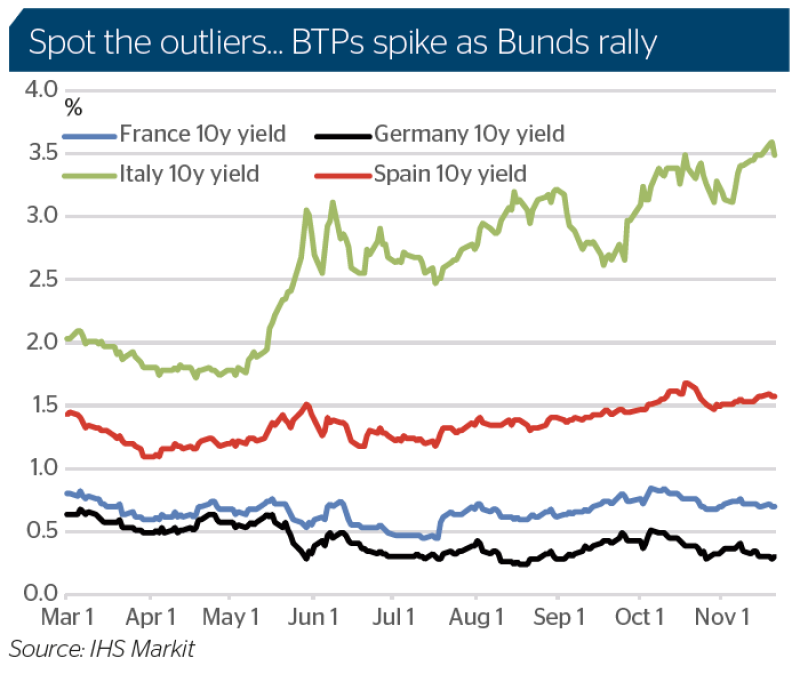

Some of that is down to the populist Italian government’s standoff with the European Commission over its budget deficit plans, which the Commission thinks are too profligate. That has led to Italian yields rocketing while Bund yields have plummeted — meaning issuers like KfW have been able to offer extremely enticing spreads over Bunds and so bring in extra orders.

Investors have also generally preferred pure German risk to, for instance, eurozone supranational trades, perhaps due to the Italian situation, which does not appear to be nearing resolution any time soon. That said, most deals in euros have been oversubscribed.

“Over most of 2018, the politically inspired volatility had little negative effect on SSA bond issuance conditions, aside from some brief periods, with deals pretty much oversubscribed and reasonably priced,” says Cumbes.

But that picture is different to some of the last few years, even with the QE effect. Worries that a populist candidate could win the French presidential election in 2017 rocked SSA markets, for instance, and some SSA bankers are concerned that those fears could return in 2019 if the Italian government becomes more aggressive in its dealings with the Commission.

And Italy it is not the only factor making issuers fret about 2019.

“I’m more concerned about geopolitical risk than anything about the curve or investor demand,” says Bart van Dooren, head of funding and investor relations at Bank Nederlandse Gemeenten in The Hague. “Investors are willing to invest in our credit and have a lot of cash.

“The bigger risks are the situation in the Middle East, the European Parliament elections [for which populist candidates are polling well] and Italy. We also have [German chancellor Angela] Merkel announcing her retirement in 2021. That will create some political turmoil and then we have, of course, Brexit on March 29, plus all the Libor, Euribor and Eonia reforms. That will cost a lot of time and the impact on markets will be bigger than just getting funding on board.”

All of this comes of course as the European Central Bank is expected to finish its quantitative easing programme at the end of 2018 — leaving less support for bonds during potentially troubled times.

“We’re at the end of the year and it’s the end of QE expansion, with one issue playing into the other,” says Barclays’ Cumbes. “We have a big buyer — the ECB — reducing dramatically going into a generally quieter year end period too, so there’s just less clarity on near term developments and that might play into perceptions of how the market performs in the first few months of the year.

“Clearly, we still have the support of substantial reinvestments that will be made in 2019, but there will be a different set of dynamics and the market will need to adjust to this, as it has started doing already.”

The reinvest guest

There is some cause for optimism from a euro point of view, however. The ECB will still reinvest cash from maturing bonds it holds next year and analysts expect it to announce its reinvestment policy at its last Governing Council meeting of the year on December 13.

The uncertainty over how that policy will look has been behind some of the investor reticence over the last few weeks, say SSA bankers, meaning clarity could bring a boost to investor confidence — alongside the support from the ECB’s reinvestment purchases in 2019.

“Given the amount of bonds the ECB has purchased, reinvestments will be significant and might provide a good support for spreads also in 2019,” says Otto Weyhausen-Brinkmann, head of new issues at KfW in Frankfurt.

“Interestingly, we twice had very large order books of over €10bn, in April and with the recent euro benchmark at the end of October. Both months had huge redemptions and hence reinvestment needs for the ECB.”

Other issuers, while acknowledging that the end of QE will certainly bring challengers, in many ways welcome that rates are likely to return to something resembling normality.

“Our assumption is that markets are going to be more volatile next year due to the withdrawal of central bank support,” says Anish Gupta, head of treasury at Oesterreichische Kontrollbank in Vienna.

“However, there should still be access to the markets and sufficient demand for high quality issuers like OeKB and the SSA sector in general.

“It is important that the rate environment normalises. That has been a challenge for banks in terms of net interest margins compressing. Most of the market participants would like to see slightly higher, normalised rates and equally central banks would like to have enough firepower in their arsenals to target interest rates as a monetary tool when the next downturn comes.

“We have had very good rates of growth over the last few years and should a downturn occur, we would want central banks to have instruments to steer the economy through such a period using standard monetary tools.”

Short back, long to the side?

That rate normalisation could also have an impact on where issuers bring deals in the euro market. QE and the ECB’s negative rates meant that short dated euro trades were off the table, while ultra-long deals as far out as 100 years suddenly became possible. But that situation could reverse as QE ends and if or when the ECB raises rates — although its position is that rates will stay where they are “at least through the summer of 2019”.

“The way the ECB handles the end of PSPP may put a bit of pressure on euro issuance or the all-in levels,” says BNG’s van Dooren. “But having said that, it also gives us more likely opportunities at the shorter end of the euro curve, by which I mean the three year part. We’ll have to compare that with three year dollars, of course, so we’ll need to see how volatile the basis swap is and where it moves.

“But like all our peers, we have to diversify.”

Not everyone is confident that rates will rise sufficiently to bring in the short end of the euro market, though.

“The front end in euros will very likely remain in negative territory, since the ECB mentioned in their outlook that they will not hike rates until summer 2019,” says KfW’s Weyhausen-Brinkmann.

“Many economists were forecasting higher yields for the end of 2018 but 10 year Bunds are still yielding less than half a percent. Given the various challenges in Europe and globally I do not think interest rates will rise significantly.”

Actions across the Atlantic from the US Federal Reserve could also have a bearing on the outlook for euro rates in 2019.

“The consensus seems to be that the ECB will start to raise rates next summer, but if the Fed pauses its increases— which is very topical to talk about these days — then how easy will it be for the ECB to raise rates sooner rather than later?” says Barclays’ Cumbes.

That hypothetical rate rise may also mean issuers will find ultra-long deals less palatable than over the last few years.

“As a general trend issuers were seeing ultra-long deals as a unique market opportunity,” says OeKB’s Gupta. “We probably will not see 70 or 100 year transactions that often, but sovereigns might want to lock in those ultra-long, low yields as long as they can.”

Lagging

As BNG’s van Dooren points out in his list of worries for 2019, the process to reform major interest rate benchmarks will also take up the time and resources of market participants. But while work to replace Libor in dollars with Sofr and in sterling with Sonia is well underway — with several floating rate notes linked to the rates printed this year — the euro market is behind the curve.

A private sector working group in September recommended the Euro Short Term Rate — dubbed Ester — as an alternative euro risk-free rate and replacement for Eonia, as well as the basis for Euribor fall-backs. But the ECB will only start publishing the rate in October 2019.

“It is a concern that the eurozone might be behind the curve in terms of Libor replacement,” says OeKB’s Gupta. “Market participants will confirm that we are probably a bit too late to come up with solutions and that the market will not have enough time to adjust properly. All of us would hope for a slightly longer adjustment period — an extension from the regulator would definitely help the market develop properly.

“Ester has been announced only very recently and that too with a very short implementation period.”