Should a company that transports oil buy greener ships? Should a Brazilian beef producer try to source cows that have not been grazed on deforested land? Should responsible investors finance their efforts to do so?

These are some of the tough questions participants in the green bond market are starting to face — questions that will become more common and insistent as the transition to a greener economy gets under way.

In 2019 the market was hit by two product innovations, which have become its hot topics. How it reacts to them will determine its future.

Transition bonds and sustainability-linked bonds contrast with each other, but share a common root: they are attempts to apply the concept of labelled bonds, which has proved so popular, to the sweeping change the whole economy must go through in the coming decade.

They also address two of green bonds’ main weaknesses. First: market participants and their body, the Green Bond Principles, have ducked the question of defining green. Second: green bonds only relate to a specific pool of the issuer’s assets. They do not give the investor any handle on what the rest of the organisation does.

Neither new product fits into the GBP’s self-regulatory framework and the organisation is debating how to respond, and whether to create new categories. Sustainability-linked bonds are particularly tricky for the organisation, which has made trackable use of proceeds its raison d’être.

“You can expect guidelines for sustainability-linked and transition bonds to be published [by the GBP] quite soon,” says a leading green bond banker.

Leaders and laggards

It was the EU’s drive for a Taxonomy of Sustainable Economic Activities that prompted the idea of transition bonds. Having begged for it for so long, market participants are pleased that an authority is about to settle the question of what is green. But the Taxonomy will leave out much of the economy, including highly polluting industries and service sectors with light environmental impact.

“The only way we are going to reach Paris is to allow an inclusive transition,” says Christopher Flensborg, head of sustainable products at SEB in Stockholm, referring to the goals of the Paris Agreement. “The transition will have three kinds of participants. The first are at the destination — most green bonds are Paris-aligned. But whether it’s housing, transport or energy, there are a lot of industries that need to catch up to get up to a transition line. The second group is the leaders who are going to take us to the next stage. Then there is the old economy, which is far behind the leaders and needs to catch up. We’re not going to succeed unless we can create an embracing transition for all three.”

Many want labelled bonds to be available to organisations whose activities may not be considered green, but which are making an effort to improve. Enter transition bonds.

Unusually, the theory has arrived before the deals. The conversation was catapulted forward in June, when Yo Takatsuki, head of ESG research and active ownership at Axa Investment Management in London, published a paper arguing for transition bonds and sketching how the market could be governed. Now, he is co-chairing a GBP working group on the issue.

While everyone is talking about transition bonds, the range of views is wide, from enthusiastic support to suspicion that they are unnecessary, or a means of greenwashing.

“Green bonds are transition bonds already,” says a green bond fund manager. “The risk is you allow some sectors and companies to change from dark brown to light brown, when maybe you want them to disappear. It allows a lot of companies to stay around and pretend they are moving in the right direction. That’s why we are not in favour of another label.”

Johanna Köb, head of responsible investment at Zurich Insurance Co in Zurich, says: “We believe that some improvement is better than none. If it makes sense, we would go into transition territory. All transitions are necessary, and all need to be financed. However, in cases where the proceeds finance meaningful climate transition, we would just call it a green bond.”

Trial and error

The fact that transition bonds need defining carefully is probably the main reason why only a handful of deals have been issued.

In 2017 Hong Kong’s Castle Peak Power issued a $500m bond, whose proceeds are used to “develop gas-fired power plants to support the transition from coal-fired power”. CPP has coal and gas plants.

In February 2019, Snam, the Italian gas transport utility, launched a €500m Climate Action Bond, for purposes including making its gas infrastructure more carbon-efficient, reducing waste and acquiring an energy efficiency consultancy.

In July came Marfrig, the Brazilian beef producer. Its $500m of proceeds are for buying cattle from Amazon ranchers who meet Marfrig’s requirements that they do not practice deforestation, slave labour or driving indigenous people off their land. Marfrig’s ability to check how its farmers behave is slight.

The deal achieved Marfrig’s tightest pricing ever, with demand from investors following environmental, social and governance strategies. But many were appalled.

An ESG investor at a major global asset manager said: “This debt issue is a pernicious influence on debt capital markets. ‘Sustainability’ should be reserved for issuers whose commitment to alternatives and/or green projects is clearly demonstrated. The very nature of their business is neither sustainable nor green.”

That encapsulates the difficulty: for every investor that wants to support a company trying to improve, another sees an old economy business that is still environmentally harmful.

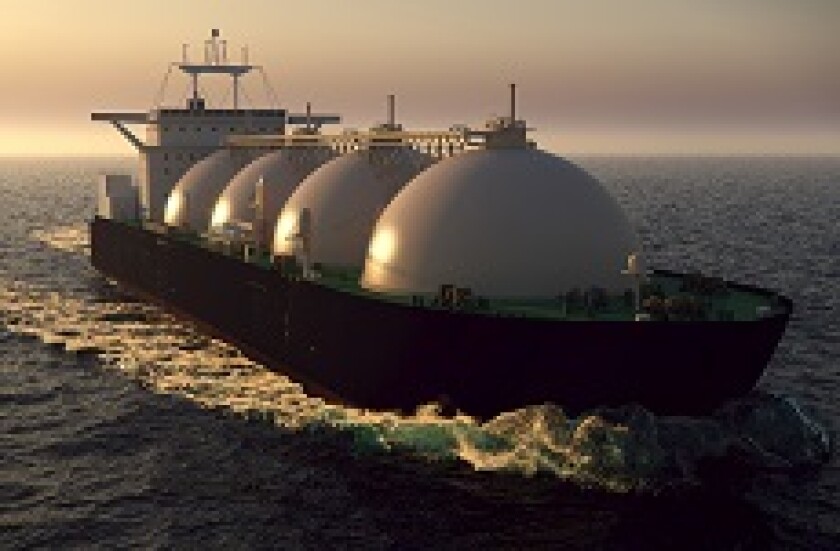

Teekay Shuttle Tankers, a shipping company serving the offshore oil industry, issued a $125m high yield bond in October that was exactly what many would call a transition bond. However, Teekay called it a green bond. It financed new tankers that run on liquefied natural gas and waste gases from the oil cargo. Teekay claims they reduce CO2 emissions by 47%, nitrogen oxides by 88% and sulphur oxides by 99%.

“We are proactively engaging with the oil sector because we want to stimulate an inclusive transition,” says Flensborg at SEB, one of the bookrunners. Although many green bond investors shunned the deal, Flensborg says: “The green element created a strong support which we guess we wouldn’t have seen in a non-green issue.”

In November Crédit Agricole issued a €100m transition bond it had designed with Axa, the sole investor, as a demonstration. Proceeds are for loans to five carbon-intensive companies cutting emissions.

Clear pathway

Many see transition bonds’ appeal and purpose, but do not want the present formless market, full of controversy. They crave some kind of order.

“The key question is: transition towards what?” says Joop Hessels, head of green, social and sustainability bonds at ABN Amro in Amsterdam. “There needs to be a definition of where you are going as a sector. Just to do something better — that is not transition. You’ve got to ask what is the desired outcome for the sector and then decide on the intermediate steps.”

Some argue the assets financed must be on a trajectory that leads to a sustainable future, such as a carbon-neutral economy by 2050.

But any bond that meets such a standard would arguably qualify as a green bond. In fact, it is a higher standard than many green bonds are held to. Energy efficiency investments, commonly found in green bond asset pools, might achieve a 30% energy saving. Is that on the path to zero carbon? The issuer’s green bond framework probably does not tell you.

It may turn out, then, that while investors would be willing to buy transition bonds, not many issuers actually find it attractive to issue them. “If you ask an issuer: ‘would you like to do a transition bond or a green bond?’ the answer most likely is a green bond,” says Hessels. But he still thinks it makes sense to have a new category: “There are certain sectors you would not automatically identify with green which are still necessary for the transition, or sectors which are not green at all, which need to change significantly to be in line with the Paris goals. There, a transition bond could potentially work.”

Strategy, not assets

In fact, the person most influential in creating the concept, Takatsuki, rejects the common description of them as a misunderstanding.

They should not, he argues, be a second tier of the green bond market for brownish issuers trying to go green. “For transition bonds, the focus is not really on the use of proceeds, but on what is going on at the issuer level,” he says.

Takatsuki sees them as a way to broaden the investor-issuer discussion from just the use of proceeds, to the issuer’s whole activities.

This kind of investment approach has always been possible, since long before green bonds were invented. However, the green bond movement ignored this and pursued transparency about a segregated asset pool.

“What we are saying with transition bonds is: ‘what are you doing as an issuer — do you have a board level commitment to stringent, sector-specific targets?'” says Takatsuki. “This is now forward-looking scenario analysis.”

If Takatsuki favours the whole company approach to ESG, it is surprising he is trying to build it out of the labelled bond market. Takatsuki is disillusioned, however, with the results from techniques such as shareholder motions. He dismisses as “rose-tinted” the view that engagement by bondholders could persuade companies to improve their ways.

The transition bond, in his mind, is a carrot — a way for investors to open the door to issuers whose environmental challenges are more difficult, and beckon them forward.

Tempting issuers like this might work — but the problem of how to define an acceptable transition will remain, and is more difficult than defining a standard green bond.

Help may be coming from the EU. In the twin track process of developing the Taxonomy — one track political, the other run by the Technical Expert Group — the drafters have thought more deeply about it. It has become apparent that there will need to be explicit recognition for transition activities. That means the Taxonomy will contain definitions.

Aiming for a target

Sustainability-linked bonds are completely different. Rather than stretching green bonds’ uses of proceeds to more difficult areas, they dispense with a specified use of proceeds altogether. The issuer can use the money as it likes — but the coupon will step up if it misses a sustainability target, on a whole company basis.

Reversing the situation with transition bonds, this product has deals, but no theory. Even though the technique is popular in syndicated loans, the bond market was startled when Enel, the Italian power and gas company, launched a $1.5bn deal in September. Participants are still getting their heads round it.

Enel’s coupon will rise by 25bp if, by the end of 2021, it fails to increase the renewable share of its generation fleet from 46% to 55%.

The company's €2.5bn follow-up deal in October also included a longer term target to cut generating emissions to 125g of CO2 a kilowatt hour by 2030.

Most dedicated green bond funds could not participate, but other investors, including ESG funds, oversubscribed the bonds heavily, pushing the spreads tighter than those on normal bonds.

“It’s a nice development of the sustainable fixed income market, though we need some time to have a strong conviction of how to use this investment and how to price it,” says an SRI bond investor in France.

Many are baffled by the product, or unimpressed. Some want to estimate the probability that Enel misses its targets, so they can value the step-up coupons. Others see the bonds as lacking “impact” because the use of proceeds is not tracked.

“For us the whole green bond concept is about transparency, reporting,” says the green bond fund manager. “You just don’t have all these features. It opens the door for less green and less credible issuers. It’s a lighter version of green bonds, an inferior structure.”

Many are anxious about whether Enel is doing anything different from what it would otherwise do; or are concerned to ensure that targets on such deals are really stretching.

“The innovation is a very interesting one for the overall sustainable investment market,” says Köb. “We believe it is important in such cases that the triggers be linked to core sustainability features of the company, and ones they primarily control — such as in Enel’s case — rather than external ESG ratings.” Enel’s triggers were 2 degree-compliant, she says, making them credible and relevant for the company type. This was “a strengthened signal of the ambition and seriousness of ESG integration of the issuer,” she adds. But unlike green bonds, Zurich does not see them as impact investments.

“It’s frustrating because the green bond concept is really going mainstream,” says the green bond fund manager. “By over-innovating this market you are creating confusion.”

The right conversation

So far, no other issuer has followed Enel. “It took a number of corporates by surprise,” says the green bond banker. “Many are looking at it and seeing if it makes sense for them. You will see more. Whether it will be the same type of explosion that we have seen on the loan side is a question — clearly the investor base is different — but there is a potential. Any sector should have a climate-related or transition-related objective and should be able to do it.”

For issuers, the structure is much simpler than a green bond. There is no need to find, tag, track and report on specific assets. “We have some issuers which work very much towards certain specific sustainability targets, but might have difficulties to add up all these incremental small investments,” says Hessels. “For these issuers it could work.”

And — the main attraction for Enel — it focuses the conversation with investors on exactly what the management wants to talk about: its core sustainability strategy.

For investors, it ought to work well too: the bonds give them an opportunity to talk to the issuer about its transition and ask whether it is going fast enough.

“Green bonds really answered the request from a lot of investors, who want to have a clear idea about how their money is used,” says the French investor, “So we have lost some transparency, but the good news is we have a better idea about the long term strategy of the issuer.”

Green bonds are not saving the world. They rarely finance green activities that would not have happened anyway, and their price advantage is small. Transition and sustainability-linked bonds, for the foreseeable future, will be no different. Organisations will not change their strategies because they can issue a different kind of bond.

What labelled bonds have done extremely well is get people talking in ways they had not before. Transition and sustainability-linked bonds can stimulate more detailed conversations about how the economy can be wrangled from its wild ways and taught more civilised habits. And both products will lay more emphasis on analysing the whole organisation, not just a section the issuer highlights. They are the next stage of expansion the green bond market has been looking for. GC