The current shock has seen a dive of a similar magnitude from $108 to south of $30 in February 2016.

The 1979 price upsurge stimulated a boom in oil investment and higher output, especially among non-OPEC producers. It also triggered a recession in consumer countries, which curbed demand. And there were redoubled efforts to achieve energy efficiency — by 1985 the US was 32% more oil efficient than it had been in 1973.

OPEC was haemorrhaging market share, which meant it had to cut its posted price or reduce production. It chose the latter, agreeing lower output quotas while Saudi Arabia assumed the role of 'swing producer’, varying output to match demand and supply. But it didn’t work.

Non-OPEC producers continued to pump and overtook OPEC output. And there was widespread quota cheating among OPEC members.

Saudi Arabia’s swing producer role resulted in slumps in its oil output and thus state revenue — down from $119bn in 1981, to $26bn in 1985 — producing a gaping fiscal hole.

Exasperated by the quota violations and alarmed by its waning international political clout, the kingdom struck back. In late 1985 it turned on the taps to defend its market share, and the oil price collapsed.

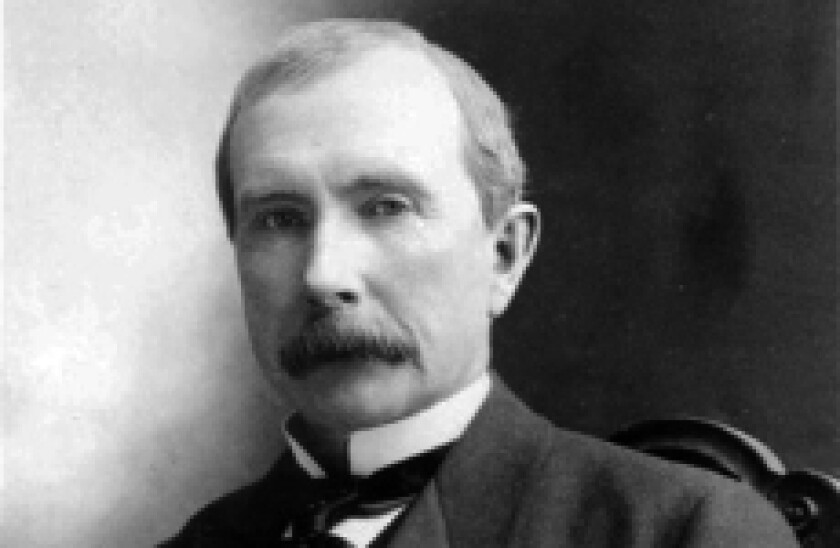

In fact, flooding the market with cheap oil to deal with rivals is a time-honoured industry practice. In the oil market’s infancy in Pennsylvania in the 1870s, oil titan John D Rockefeller had used a “good sweating”, as he called it, to force independents to sell out to his Standard Oil trust.

Thanks to such tactics, Standard Oil emerged from the oil wars of the 1870s in control of 90% of US refining capacity. Oligopoly brought stable prices to the industry, a feat later replicated by the oil majors and then OPEC in its heyday.

Saudi Arabia’s “good sweating” of 1986 also resulted in a stable outcome. There were revised OPEC quotas, increased output co-operation by non-OPEC producers, and a new reference price emerged of $18 a barrel, roughly twice the low-point, and a level that completely wiped out the price hike of 1979. The new nominal price held more or less steady over the following 15 years, drifting gently lower on an inflation-adjusted basis.

In 1986 the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the international central bankers’ forum, greeted the "novel kind of oil shock" optimistically, anticipating a decline in inflation and an acceleration in output growth in industrial countries.

It was estimated that the 1986 oil price fall transferred $50bn to consuming countries. In the short term, some of those funds went into stock markets contributing to a price bubble that burst spectacularly in October 1987, wiping a third off equity prices. But the crash proved to be just a correction and the era of growth, profits and low inflation from the mid-1980s to the mid-2000s has become known as the Great Moderation. A key underlying factor was a moderate and stable oil price.

The oil price began to motor in the early 2000s, rising five-fold from $20 to $100 by 2014, fuelled by demand from China and other emerging markets, and rising production costs.

As ever, higher prices stimulated investment and output by a variety of energy producers, notably US shale oil frackers.

Once again, Saudi Arabia found itself losing market share and this time against the background of heightened anxieties about regional political and military challenges. Cue another “good sweating”.

The current 70% fall from the post-financial crisis oil price level is similar in magnitude to the relative level in summer 1986. On the basis of this historical benchmark, a 1986-magnitude rebound from bottom would suggest a medium term nominal oil price of around $50-$60, to underpin a new era of moderation.

That is hardly the way things are perceived by jittery markets and consumers today; but nor was it in the wake of the 1986 “good sweating”, when the BIS noted that instead of celebrating the oil price benefaction the prevailing mood, buffeted by frequent external shocks, was “wait and see”.