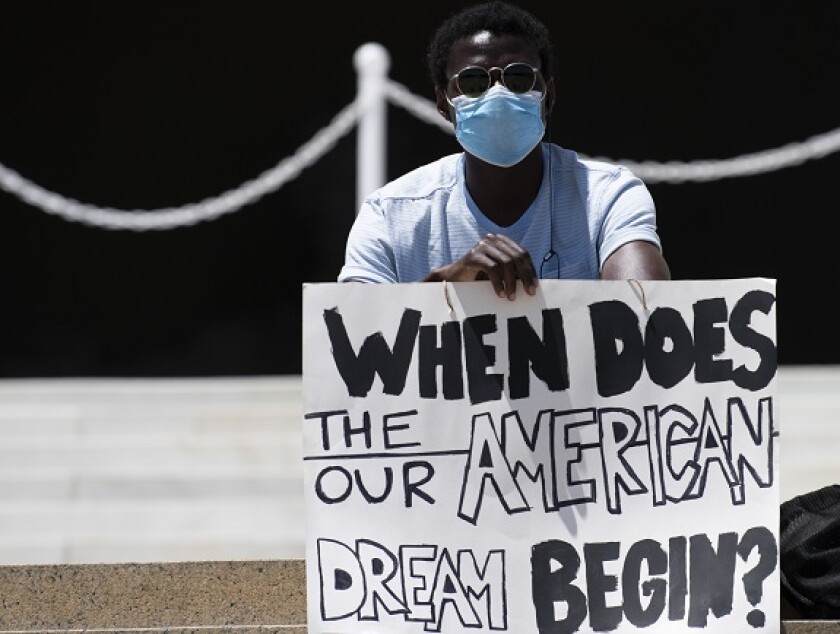

Faced with the horror of a helpless African-American man dying under the knee of a police officer, in full view of colleagues and passers-by, many feel rage, bordering on despair. That such a thing could happen, fully 50 years after the civil rights movement, is an appalling indication that far too little progress has been made in reducing legal and economic injustice.

This will come as no surprise to black Americans — or to ethnic minority citizens in Europe and many other countries, who also face disadvantage and prejudice.

It is nevertheless shocking to all. The death of George Floyd in Minneapolis has provoked an unusually strong reaction from corporate America, with many CEOs publicly stating their dismay at the event and recognition that it shows a deep-seated wrong at the heart of the nation.

“Despite the progress the United States has made, Black Americans are too often denied basic privileges that others take for granted,” wrote Mark Mason, CFO of Citigroup, on the bank’s blog. “I am not talking about the privileges of wealth, education or job opportunities. I’m talking about fundamental human and civil rights and the dignity and respect that comes with them. I’m talking about something as mundane as going for a jog.”

Saying the right things

The significance of the wave of statements should not be underestimated. It helps that many of the most influential and recognisable people in American life are aligning themselves with the acknowledgement that society is unjust.

It is particularly welcome that many of the business leaders who have spoken out are not just condemning a crime, as if it had nothing to do with them. Some, including Tim Cook, CEO of Apple, and Bob Iger at Disney, said they would further strengthen their commitments to diversity within their own companies.

However, it is easy, in corporate life, to feel impotent. Our role is to do our jobs as best we can. How can we do anything about police brutality or the spirals of economic hardship and lack of opportunity that grip many communities?

This paralysis is only made more obvious by the philanthropic donations many companies are making to racial justice groups, such as $10m from Facebook. If charity-funded NGOs are needed to promote equality before the law, it shows that the problem is mountainous.

It’s your economy

And the other side of these corporate declarations’ significance is their insignificance.

As other observers have eloquently pointed out, the rich and powerful to a substantial extent created the society we have now. The inequality of wealth and opportunity — in the US, but also across the developed and developing worlds — proves how much they benefit from it.

In aggregate, the US economy — and to a considerable extent society — is US companies.

Large corporations set the wages, training and working conditions for their staff. They decide where to invest and locate workplaces. Some, like Amazon, have huge power in the markets they operate in, so have little cause to object that they are beset by price competition.

Virtually all have cut and offshored jobs or replaced humans with robots or software when they could raise profits by doing so. GlobalCapital has recently used an artificial intelligence app to transcribe panel discussions, rather than the workers who used to do it.

Big companies also operate in and support countries where injustice and the deprivation of rights is far graver than in the US. Apple has been criticised for not speaking up about China’s oppression of its Uighur Muslim minority.

Who governs?

Corporations sometimes behave with a worrying degree of autonomy — appearing to serve management first, shareholders second and other people they come into contact with a distant third.

But they are not autonomous. They belong to shareholders and are financed by bondholders and banks. In most cases, that means ordinary people, through pension funds, insurance companies and investment funds.

That should, technically be an example of democracy — power resting with the people. The reality is far from that.

Hardly any private individuals exercise any real influence over the companies their savings are invested in, either by voting in shareholder meetings or deciding which securities to buy. With the investment system structured as it is, the very thought of trying is exhausting.

Power over corporate behaviour is divided between corporate management, investment institutions and the government and regulators that set the rules.

Some investors know their authority and use it — above all, private equity firms. Think of KKR taking a €130m dividend from Spanish fast food deliverer Telepizza last year after delisting it, leaving a company with a straightforward business model, which ought to function well, overstretched financially and in danger of default.

But in many listed companies, there is a power vacuum. Investors are too fragmented; too hampered by rules, conventions and politeness; and often simply too busy to really think about how the companies they are investing in behave and what they could do about it.

Sweet talk

Everyone who works in the capital markets and investment industry has now heard of responsible investing and environmental, social and governance issues. Most could give you a reasonable definition and plenty of them will take any opportunity to trumpet how important it is to them and their organisations.

But try asking them which companies should one not invest in, even if they are profitable, because their impact on the environment and society is too bad. Most would find it hard to answer — or might mumble something about coal or child labour. Subject to a little hand-wringing, in other words, they are OK with the status quo.

Nevertheless, the investment industry blares out the message that it is now investing responsibly and trying to do so sustainably.

How many times this year have you heard the idea that the “S” in “ESG” is getting more focus because of the coronavirus?

If that is to mean anything, it has to mean action, not just words. Action does not mean labelling bonds as Covid-19 — although the marketing may save a few basis points.

It means investors proactively exercising the power they have through the capital markets to steer companies — and hence the economy — in a more socially beneficial direction.

Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, is often seen as the voice of the zeitgeist in the investment industry. In 2018 he called for capitalism with purpose; in January this year he recognised the urgency of climate change. This week he said “No organisation is immune from the challenges posed by racial bias.”

But BlackRock fails to support shareholder motions calling for progressive policies at companies — often very mild ones simply asking for more disclosure. Worse: in 93% of cases in 2019, it voted against them, according to Morningstar research.

Passive management is no excuse: Fidelity’s index funds have moved from backing no ESG resolutions in 2016 to over half last year. There has been no revolt by aggrieved customers.

Bondholders asleep

At least it is generally understood that shareholders can direct companies by voting, engaging and withholding investment.

Bondholders consistently underestimate the clout they have. This has gone on so long it is beginning to look like they don’t want to acknowledge it. Debt investors may not have an AGM at which to file motions, but they have roadshows at which to ask questions, and investment bank salespeople to give feedback to.

Companies hate controversy. One awkward question in a bond investor meeting or call will embarrass finance executives. If the issue crops up regularly, treasurers and CFOs will pass the message to the CEO.

BlackRock may think its private engagement chats with companies are effective; but what firms hate is the threat of losing investors, especially if this is public.

What can I do?

If investors are genuine about lamenting inequality in the US, or anywhere else, they can do something about it.

They can scrutinise companies’ diversity policies. Are they hiring and promoting enough women and ethnic minority workers, including in leadership roles? Are they making efforts to overcome bias in society, such as unequal access to education?

They can examine working practices. Do firms pay staff enough to live decently — bearing in mind how far they have to travel to work and how they manage childcare? Do they duck responsibilities on pay and healthcare insurance by outsourcing work to contractors? Many US equity portfolios include Amazon but how much does the portfolio manager know about the life of an employee there? Or a Foxconn worker supplying Apple? Or an Uber driver?

They can tackle executive pay. It might not make much difference to a company’s finances, but it sends a very strong message about who society is organised to help.

They can clamp down on corporate tax “efficiency”, otherwise known as avoidance. This is one of the most shockingly widespread ways in which those wealthy enough to own shares take resources from those who rely on government support to make ends meet. Until recently, it has gone almost wholly unpunished by shareholders and bondholders.

They can express, through their interaction with regulators, their support for regulations that foster fairness and opportunity in the workplace, and transparency and strong ethics in corporate governance — including allowing investors to express their wishes to management.

There are still issues outside corporate control — human and civil rights, public education, access to healthcare, the justice system.

Except they aren’t. If any democracy is to be reformed, to become more socially inclusive, healthier and more just — as a large share of people including financial market participants want — this must be achieved by elected representatives.

Particularly in the US, corporations — which means institutional investors — have enormous, direct influence on politics, through lobbying and campaign donations.

That means companies using shareholders’ money to change — or not change — US society. The healthcare system, for example, has been shaped by what the health insurers want.

Investors can demand that companies are transparent about their lobbying and donations, and follow their owners’ wishes in these matters. If firms will not comply with this basic request, institutions should divest.

Mark Mason movingly repeated George Floyd’s last words: “I can’t breathe.”

For too many in society, that is how they feel, day in, day out. Those with money know this, and are often sympathetic. They now need to do something about it.