The existing crop of Sino-foreign JVs can trace their history to the mid-2000s, when Goldman Sachs and UBS inherited the licences of Hainan Securities and Beijing Securities after lending a hand to their bailouts. That gave them majority control of the firms known today as Goldman Sachs Gao Hua and UBS Securities.

A clutch of similar ventures followed suit, including from Citi, Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank, JP Morgan and Morgan Stanley. But unlike Goldman and UBS, they were limited to a minority interest in their JVs and prohibited from carrying out brokerage activities.

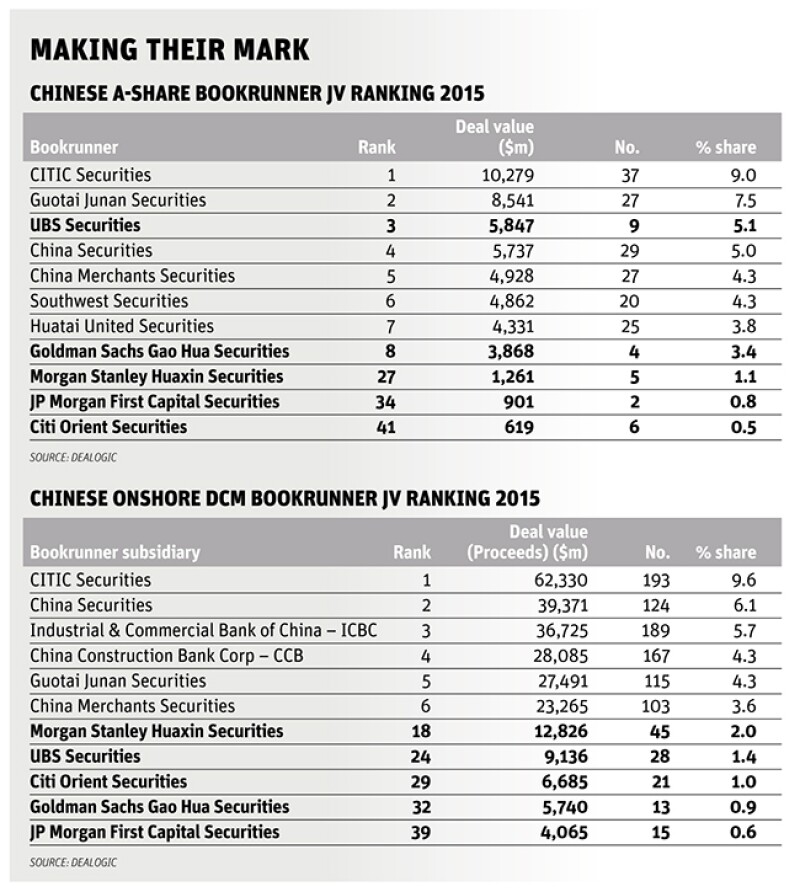

Today a number of those firms are thriving, and they have the numbers to show for it. Goldman Sachs Gao Hua and UBS Securities have broken into the ranks of the top 10 bookrunners in A-share equity capital markets, according to Dealogic.

UBS Securities finished 2015 at third place, behind only Citic Securities and Guotai Junan Securities. It earned league table credit for deals worth $5.85bn – more than half of Citic’s total. Goldman Sachs Gao Hua was in eighth place with $3.87bn.

The JVs figured less prominently in onshore debt capital markets, with the top 10 list dominated by domestic securities houses in 2015. But Morgan Stanley Huaxin Securities pulled ahead of the competition, bringing deals worth $12.83bn and a 18th placing on the league table.

Eyes open

“The JVs have done as well or better than expected based on a realistic understanding of the competition and the areas they can play in,” said Matthew Phillips, PwC’s China and Hong Kong financial services leader. “They had no illusions about the size of the opportunity or the length of time needed.”

But to get to where they are now has required no small amount of patience. For the first 10 years, the Sino-foreign JVs struggled to be consistently profitable. For example, in 2012, five of the 10 JVs lost money.

Then in October that year, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) announced a moratorium on IPOs that lasted 14 months. The freeze took a toll on deal flow, and with most of the JVs restricted to underwriting trades in primary, they had little respite.

Hammering out partnerships was a challenge too. A senior source with an international bank in Hong Kong recalls that while the international firms may have been keen to access China’s cloistered securities industry, their domestic counterparts were less so. “After the 2008 global financial crisis hardly any of the Chinese institutions were interested in setting up a JV,” he said. “They saw no reason to give away a third of their equity, and some even asked for guaranteed revenues, which of course the banks refused.”

Yet many persisted with the belief that a China JV was essential and continued sniffing out partnerships.

“Having a great onshore JV is like being able to wave a flag for your brand,” said Keith Pogson, Ernst & Young senior partner for financial services, Asia Pacific. “If you want to be a global bank with a credible franchise in China, how can you not be onshore?”

According to data from the Securities Association of China, in 2014 UBS Securities posted Rmb118.1m ($18.2m) in net profit, Goldman Sachs Gao Hua Rmb58.1m and Citi Orient Securities Rmb52.2m. This rose to Rmb235.6m for UBS Securities and Rmb162.8m for Citi Orient in the first half of 2015 — the latest period for which figures are available — buoyed by the bull market in A-shares and corporate bond issuance. Goldman Sachs Gao Hua raked in Rmb31.9m.

Bounce back

For Citi, which agreed to form Citi Orient in mid-2011 but only got the business up and running a year later, the suspension on IPOs could not have come at a more trying time.

Its response was to diversify its offering and pour resources into areas including corporate bond issuance, M&A and securitization, said Kenneth Koo, deputy general manager and Citi’s chief representative at Citi Orient.

The securitization aspect was key. After China put A-share IPOs on ice, banks were forced to diversify and fast. Citi Orient pushed into a then-burgeoning market for asset-backed securities, which allowed it to earn higher fees compared with traditional equity products because of the complexity involved.

In a transaction that cemented the JV’s reputation in securitization, Citi Orient led the issuance of an Rmb3bn microloan ABS in 2013 for e-commerce giant Alibaba. The underlying assets were unsecured microloans to micro enterprises and sole proprietors.

“It was a landmark deal,” Koo said of the Alibaba ABS. “Because of several novel structural features, including the first ABS based on microcredit to consumers and merchants, we were not sure if the CSRC would approve it. Today Citi Orient punches above its weight in the securitization market.”

The figures would seem to back this up. Citi Orient ranked seventh for onshore asset and mortgage-backed securities in 2015 with five deals worth $2.11bn, according to Dealogic. Following closely behind was JP Morgan First Capital Securities, which brought seven deals worth $2.06bn.

PwC’s Phillips agrees that the JVs must find a niche. “Being one of 10 or more banks on a high profile outbound deal or listing is good for rankings. But just as important are the mid-sized deals the JVs nurture themselves and are uniquely placed to execute because of their local connections and global relationships. Here they take the lion share of the healthier fees on offer.”

Like Citi, UBS Securities also found ways to weather the IPO suspension. To make up for fewer listings, the firm turned to follow-on issuance and debt capital markets. It helped that UBS Securities had access to an equity trading and brokerage business through the licence it inherited.

But UBS had the added advantage of being among the earliest to qualify as a Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII) in 2003 with a quota of $800m. That quota came in handy during the 2012 moratorium, as the Swiss bank leveraged it to become the market leader in A-share trading for QFII clients.

QFII was the first official programme allowing foreign fund owners and fund managers, typically long-only investors, to gain entry into China’s capital markets. It remains the largest of the inbound investment schemes and total quotas now stand at $91bn, according to data from CEIC.

New players

But while the incumbents are now on a strong footing after weathering various crises, the end of 2015 brought news that is set to shake up the sector again.

In November, HSBC started the ball rolling on a JV of its own. The structure it has chosen, however, will break with the past.

Instead of the 33% shareholding limit imposed on older JVs, HSBC’s agreement will give it a 51% stake in the venture. The bank also aims to offer a broad spectrum of investment banking services, including the ability to trade in the secondary market.

In addition, it will not be tying up with another Chinese brokerage but Shenzhen Qianhai Financial Holdings – a state-owned entity that has a government mandate to promote and develop the Qianhai Shenzhen-Hong Kong Modern Service Industry Cooperation Zone, a special economic zone in Guangdong.

“This JV is further evidence of HSBC’s determination to be part of China’s economic development, grow our business in the Pearl River Delta and throughout the country and support the innovative approach to reform and liberalisation that policymakers are undertaking,” HSBC group chief executive Stuart Gulliver said in a statement in November.

The onshore venture was made possible thanks to an amendment to Supplement X of the Mainland and Hong Kong Closer Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) last August.

The agreement, signed in 2013, allows Hong Kong or Macau-funded institutions to set up one JV in each of Guangdong, Shanghai and Shenzhen with a maximum shareholding of 51%. At the time however, the criteria for which firms were eligible was unclear.

Then in August 2015, the CSRC said that an investor must be a licenced financial institution or financial holding company registered and headquartered in Hong Kong. Also, the investor or its controlling entity must be listed in Hong Kong, with at least 50% of pre-tax profits derived from the city.

HSBC qualifies as its Asian unit, the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corp, is headquartered and funded in Hong Kong. But it was not the only one to jump on the opportunity. In December, the Bank of East Asia said that it would also be starting a fully licenced securities JV with Qianhai. Both ventures are still subject to regulatory approval.

Credit Suisse also announced in November that its JV Credit Suisse Founder Securities won approval to provide brokerage services in Shenzhen Qianhai from CSRC.

These are all signs the regulator is becoming more comfortable with foreign ownership in the financial sector, said an analyst. “It echoes the central government’s stand on reform and efforts to introduce more foreign participation in the capital markets,” he said.

Nicole Yuen, vice chairman for Greater China and head of Greater China equities at Credit Suisse, said its JV’s brokerage licence will not only give Credit Suisse Founder a new revenue stream but also build on the Swiss bank’s key strength in China – equity research.

Credit Suisse’s research coverage spans over 1,200 A-share companies in Shanghai and Shenzhen, the biggest for a foreign bank, said Yuen. The trading licence means it can now broke to clients offshore, which it had been doing via the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect, and also locally in China via the JV.

For HSBC, when the JV is approved, one of its first priorities will be to launch an onshore debt business, amid a boom this year in renminbi bond issuance on the Mainland on the back of falling interest rates. Bonds is also HSBC’s strongest suit offshore with the bank regularly topping the leagues tables for Asia ex Japan. Its Hong Kong arm was also one of the first issuers to sell a Panda bond when the onshore renminbi market was reopened to foreign issuers in September.

“We are excited about this,” Gordon French, head of global banking and markets, Asia Pacific for HSBC told

Asiamoney. “It’s a great entry point into China but we are also cognisant that we are building this business for the long term.”

Curious timing

In many ways the JV is a natural fit for HSBC, which traces its roots to Hong Kong and Shanghai. But the timing of the venture, set against major upheaval in China’s financial markets, means the new JVs could face an even tougher challenge than their predecessors.

Investor sentiment has soured on China after a series of policy gaffes by the government, including the boom and bust in A-shares and a surprise devaluation of the renminbi that stoked fears of a recession. Last year was the most tumultuous in a decade for Chinese equities.

“The renminbi issues are very serious, perhaps even more than the A-share crash,” the senior banker said. “It’s causing lots of angst and poses fundamental questions about China’s economy. The big risk is how policymakers will respond. If they dial back on reforms we could see more outflows.”

Adding to the concerns was Moody's decision on March 2 to change its outlook on China's Aa3 government bond rating to negative from stable, citing weakening fiscal metrics and the continued fall in foreign exchange reserves. “Without credible and efficient reforms, China's GDP growth would slow more markedly as a high debt burden dampens business investment,” the ratings agency said.

Still, Credit Suisse’s Yuen thinks now is a good a time as any to build out its China franchise.

“In a bull market it’s often difficult to expand into a new business because everyone is busy chasing their existing business,” she said. “But the market has given us a breather now, and there are clear benefits, such as the availability of talent and resources. China is a strategic market for Credit Suisse, so we will expand regardless.”

HSBC’s French also believes the right talent may be easier to attract in a challenging market.

Its JV, he added, is an important component of HSBC’s Asia pivot and China strategy. The model the JV will seek to emulate is that of its own global banking and markets unit in Hong Kong, and HSBC plans to build similar capabilities onshore so that it can offer clients an equivalent choice of offshore and domestic services.

In the meantime, the bank has been keen to manage expectations. With the JV still at the pre-approval stage, there is little indication as to when it will begin operations.

The analyst said that with or without a securities JV, HSBC has always been one to watch in China because of its onshore commercial banking presence, the largest of any foreign bank.

“HSBC’s onshore bank and JV could be a powerful combination, but it boils down to execution,” the analyst said, adding that market participants will be waiting to see how HSBC puts its vast balance sheet to work as a securities house.

In addition, there may be disadvantages to entering the securities industry without an established partner, reckoned the analyst. On the flipside, starting from scratch means HSBC will not have to inherit the legacy issues that come with partnering an established business. Few would also doubt the strength of its partner, which as an arm of the state exudes considerably more clout than a private entity.

“What we aim to build is an unprecedented JV that isn’t based on any legacy platform,” said French. “We want to create a business that lasts a long time, is relevant to clients and sustainable.”

Secret sauce

That commitment to investing for the long term is an approach echoed by many others. “There is no silver bullet,” said PwC’s Phillips. “But if you are willing to take a longer-term view and bring the best of what you have to offer clients onshore and offshore, then the JV has a good chance of being successful.”

Another key to success for the JVs is integration between onshore and offshore. But avoiding messy turf wars is easier said than done. The senior banker said JVs often suffer from a silo mentality where onshore bankers push their products at the expense of everything else. Some firms have done a better job of collaborating than others. A source close to Goldman Sachs Gao Hua said that internally, the firm does not distinguish between its A- and H-share teams.

That kind of synergy was what helped Goldman Sachs Gao Hua execute, on a sole basis, the Rmb12.7bn secondary placement in Shanghai-listed Industrial Bank Co in February 2015. The trade, which saw Goldman pull off the first ever institutionally marketed A-share block sale in China, was a coup for the bank and the JV.

Eugene Qian, president and country head of UBS’ China business, said its corporate client solutions (CCS) teams in the Mainland and Hong Kong work as a single, fully integrated function to serve Chinese clients.

“Since many clients have both A- and H-shares listed in Shanghai, Shenzhen and Hong Kong, they prefer to deal with a bank that can offer an integrated service onshore as well as offshore,” Qian said.

Moreover, having management control means it can ensure the quality of staff is on par with UBS’ global standards. Its bankers rotate regularly between the Mainland and Hong Kong so that the bank has virtually one platform onshore and off.

Reform question

Still, with global financial markets in flux, Qian reckons that 2016 will be a year of adjustment for China’s economy and capital markets. The entire process could take more than 12 months, he said.

“However, China remains determined to execute the reform agenda and will continue with renminbi internationalisation. The government will no longer provide stimulus for all industries, but it is offering support to industries which are sustainable.”

For its part, UBS is sticking to its commitment to China. CEO Sergio Ermotti said last year that the Swiss lender is aiming to double its staff strength in China over five years and add about 600 people across wealth management, investment banking, equities, fixed income and asset management.

As always with China, the sands are constantly shifting. Bankers at the JVs say they are cautiously optimistic about the future, but many are also counting on Chinese companies to continue venturing abroad and grow domestically, all of which is positive for capital markets.

The trick, for some, is to keep their eye on the prize. “We are feeling good here and are busy,” said Citi’s Koo.

“Without being on the ground in the form of a JV, it’s hard for people to truly understand the significance, direction and speed of transformation in China’s domestic financial markets. An onshore presence is crucial. We have hardly scratched the surface of China’s potential.”