If China’s economy is in trouble there is no sign of it in Challhuahuacho, a chaotic mining town high in the Peruvian Andes.

Challhuahuacho may be thousands of miles from China but Chinese-owned MMG Limited is the town’s lifeblood as it moves to complete the massive Las Bambas copper project that will require close to $10bn in investment when finished and will start producing 400,000 tonnes a year of the red ore in 2016. Peru produced 1.4m tonnes of copper last year.

Mayor Antolín Chipani shrugs about China’s slower growth and the devaluation of the yuan, saying he has not seen any changes. “Las Bambas will be finished soon and start producing copper,” he says. “We don’t expect the Chinese to make changes now.”

Across the mountains in the Junín region, China’s Chinalco Mining Corporation announced in late August that it would move ahead with a $1.3bn expansion of its Toromocho copper mine. The expansion comes on top of $3.5bn already invested and will increase production above 300,000 tonnes of copper annually.

In addition to these projects, Chinese mining companies in Peru have a long list of other vast mining projects with combined planned investment totalling more than $15bn.

The story is repeated throughout the region, with Chinese companies having gobbled up mining concessions in countries like Peru and Ecuador, invested in energy projects from Mexico down to Argentina and lent — or pledged — huge sums to Brazil and Venezuela. The China National Petroleum Corporation is the largest oil producer in the country.

Cynthia Sanborn, a political science professor at Peru’s Universidad del Pacífico who has closely watched Chinese investment, says she does not expect any major changes. “China’s economy has slowed but there is still the need to secure natural resources. There could be delays in some projects but I don’t expect any huge disruptions in capital flows,” she says.

What is changing in Latin America is the profile of the projects that China is considering, especially with infrastructure, which appear more like its ambitious economic corridor with Pakistan than anything it has attempted in the Latin American region so far.

CHINA INC.

“China Inc. is moving into a new phase,” says Jennifer Turner, director of the China Environment Forum at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, DC. “They can do infrastructure at a speed and level that makes your head spin. They are looking to diversify their investment and are now taking overseas their capacity to build massive infrastructure.”

Chinese companies have built the largest hydroelectric electric plant in Ecuador and had planned a $3.7bn bullet train in Mexico until the Mexican government reneged on the project.

These projects, however, pale in comparison to two massive transportation endeavours — an interoceanic canal through Nicaragua and a bi-oceanic railroad through Brazil and Peru — that would upend trading routes and could radically alter the perceptions Latin Americans have of China’s role in the region.

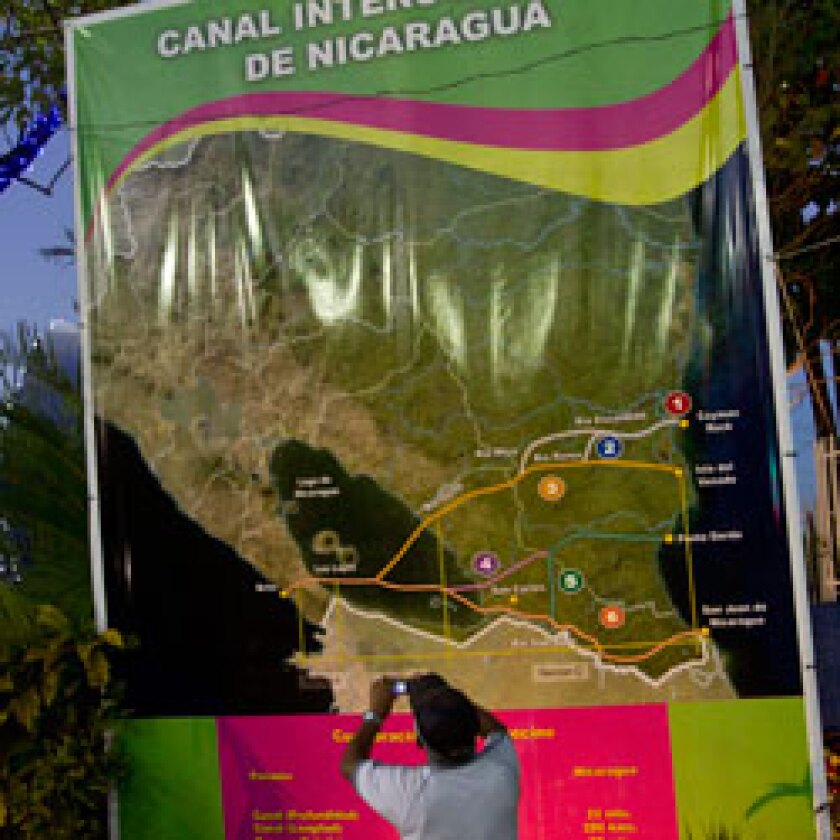

Nicaragua’s Congress approved in 2013 a plan for the 173 mile canal proposed by Chinese billionaire Wang Jing. Wang’s Hong Kong Nicaragua Canal Development Investment Company (HKND) was given a 50 year renewable contract to build and operate the canal and a series of related projects, including a new international airport, ports, roads and tourist resorts.

The price tag is now estimated to be at least $50bn and some preliminary work has started, but Wang is still looking for investors to pay for the project. In the meantime, a 14 volume environmental impact assessment submitted at the end of May by Britain’s Environmental Resources Management (ERM) is under consideration.

A follow-up study to complement ERM’s report is already planned, says Telémaco Talavera, an adviser to Nicaraguan president Daniel Ortega and the canal project’s spokesperson.

The project has raised a number of red flags, from its cost to the environmental impacts as well as Wang’s own financial possibilities and capacity to raise the capital required for an undertaking of this magnitude.

The loudest objections have come from environmental groups both inside and outside Nicaragua, questioning the impact of the proposed canal on Lake Nicaragua, the largest body of fresh water in Central America and the second largest in Latin America, and two environmentally protected zones it will cross.

Environmental groups in neighbouring countries say the canal would radically alter water patterns in Central America, undermining agriculture and other income-generating sectors.

Talavera says the criticisms are unfounded and, in some cases, purely political. “This would be a game-changer for Central America and the region as a whole. It will allow ships that are too large even for the expanded Panama Canal to move between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans,” he says.

He says that China’s capacity for large scale infrastructure projects gives it the know-how to build the canal and that safeguards have been built in to guarantee that environmental impacts are kept to a minimum. He also scoffs at the idea that the slowdown in China’s economy is a problem.

“The comments out there make it seem like China’s economy is falling apart but this is the farthest thing from the truth. China is not growing by 10% but it is growing by 7% and what country out there would not like to see this,” he says.

TRANSCONTINENTAL RAIL

The bi-oceanic railway that would traverse Brazil and Peru is a new take on a proposal that has been floated and dropped for nearly a century. It resurfaced last year and gained ground when Premier Li visited Brazil and Peru in May. The 5,000 mile rail project would link ports in Brazil to Peru’s northern Piura port and would travel through virgin rainforest. The price would be more than $50bn.

The Brazilian, Chinese and Peruvian governments agreed to carry out different studies, with the Latin American governments working on initial environmental impact assessments and China financing the financial feasibility studies. The railroad, like the canal in Nicaragua, has raised a series of concerns and even political wrangling in Brazil and Peru as well as in neighbouring countries.

Unlike the canal route in Nicaragua, a large swathe of the planned railroad would cut through unexplored areas. Henderson Rengifo, head of an umbrella organisation of Peruvian indigenous groups (AIDESEP), says the railroad would be devastating for the environment and native groups, including some who continue to live in isolation. “This is a mega-project and experiences in Peru and elsewhere show that the impact is tremendously negative,” he says.

Omar Jiménez, governor of Peru’s southern Tacna region, says one way around the problem would be a different route, one that would follow an inter-oceanic highway built in the previous decade that links Brazilian and Peruvian ports. He says a southern route is more sensible because it “coincides with a larger vision of South American integration”. The southern route could also link Bolivia into the plan, something that President Evo Morales has demanded.

Miguel Vega-Alvear, head of the Peru-Brazil Chamber of Commerce, says the railway, regardless of the final route chosen, would have multiple benefits for Peru. He says it would turn Peru into a hub for goods arriving from China and leaving the region. “Peru would become the trading platform for South America,” he says.

China is the largest trading partner of both Brazil and Peru. China-Brazil trade in 2014 was more than $80bn, while China-Peru trade was $16bn. Peru implemented a bilateral free trade agreement with China in 2010 and both countries form part of the 21-economy Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec) forum.

Brazil is the only country in Latin America to sign up as a founding member of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and, with China, is part of New Development Bank or Brics (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) Bank.

SAVING FACE, LOSING MONEY

The railroad proposal, however, came before the explosion of the corruption scandal in Brazil involving state oil company Petrobras. The scandal also appears to have regional tentacles, and authorities in Peru are investigating alleged kickbacks involving Brazilian firms that built the inter-oceanic highway.

Paulo Sotero, director of the Brazil Institute at the Woodrow Wilson Center, says the proposal will inevitably be slowed by the corruption scandal. “Considering the ongoing crisis in Brazil and its implications of corruption in major public works projects in Brazil currently under federal investigation, it will take a while for this proposal to leave the drawing board,” he says.

The railway has already started to seep into Peru’s presidential race. Elections will be held in April 2016. Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, a leading presidential candidate, has called the railway excessive and unnecessary. He said Peru should focus on its own transportation infrastructure, which lags behind neighbouring countries, “before considering a project that will let Brazil transport goods to China”.

Economic feasibility could be the determining factor. A study by the International Union of Railways (UIC) found that the cost of moving soybeans by rail — Brazil is China’s major soybean supplier — would cost more than using existing maritime routes.

Questions have also been raised about the need to have inter-oceanic highways, a bi-oceanic railway and a new inter-ocean canal in addition to the Panama Canal and other existing maritime routes.

Nicaragua’s Talavera, who was in Peru last month to explain the canal project, said the canal and railway would actually complement each other. “We have analysed the proposal to build the train and we have concluded that they would not be in competition with the canal for goods. It is important to point out that the two options, when completed, would still only move a fraction of the world’s merchandise. I don’t think that these will be the only projects.”

Christopher Ecclestone, of Britain’s Hallgarten & Co portfolio management company, says although China has the capacity for large infrastructure projects, its leaders have to recognise when an idea might look good on paper but is not feasible.

“The Chinese ego will need a pin stuck in it to deflate some of its expectations; whether they stick it into themselves or reality does it will be the same effect,” he says. “Loss of face, of course, is the big thing for the Chinese, so to abandon such projects will involve losing face. However, it is cheaper to lose face than to lose billions.”