After an unexpectedly crisis-free first quarter of 2012, financial markets are showing increasing signs of nervousness about the eurozone. As the tonic effect of the European Central Bank’s three year longer term refinancing operation (LTRO) fades, economic fundamentals are starting to vie with liquidity in shaping sentiment. The recent jitters about Spain are the first blot on the eurozone’s post-LTRO landscape.

There are good reasons to fret about Spain. Its property-fuelled growth model has collapsed. Its total debt as a share of GDP is roughly on a par with Portugal’s and is the second-highest after Ireland’s among the eurozone’s five peripheral economies. Its fiscal deficit last year was a staggering 8.5% of GDP. Unemployment is sky-high, while the share of bad loans in an already sickly banking sector is rising sharply as the economy contracts.

Yet this is all old hat for government bond investors. So why the sudden bout of anxiety? The prevailing view is that Spanish prime minister Mariano Rajoy’s decision in early March to breach the country’s budget deficit target for this year unsettled the markets. Possibly, but then did investors really expect Spain to slash its deficit by over four percentage points of GDP in the space of just eight months, and in the teeth of a shrinking economy?

Not the full Monti

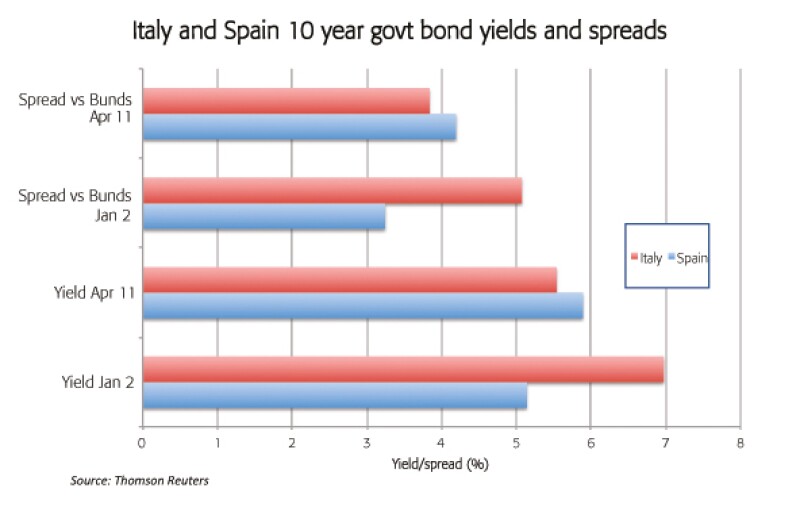

A more likely explanation is that Italy, the focal point for investor angst at the end of last year, is now judged to be a stronger credit. In pricing terms, Italy has benefited much more from the ECB’s largesse, with the yield on its 10-year paper still some 130bp lower than at the start of 2012. Mario Monti, Italy’s technocratic premier, has restored the government’s credibility and played his political cards adeptly — both at home and abroad.

The chilling prospect of a couple of failed Italian bond auctions in the first quarter of this year seems almost a distant memory. While it is Mario Draghi, the new president of the ECB, who deserves most of the credit for having shored up the Italian and Spanish bond markets, Monti’s government has exceeded investors’ expectations while Rajoy’s has fallen short of them.

Yet there should be no schadenfreude in Rome. The eurozone crisis has not been resolved. The LTRO has raised the stakes further by tying the Spanish and Italian sovereigns and their carry-trading domestic banks closer together. If fears about Spain intensify in the coming days, Italy will not be spared. The yield on Italian 10-year paper has already been creeping up, partly because of growing concern about Spain but also because troubles are brewing in Italy.

Monti’s €20bn austerity package aimed at balancing the country’s budget next year is being launched while the economy is already in a technical recession. Much-needed structural reforms are being watered down, mainly in order to placate the two main parties in parliament on whose support the government depends. The “Monti effect” — which, in all fairness, stems from the fact that José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (Rajoy’s more or less responsible predecessor) was not Silvio Berlusconi (Monti’s scandal-plagued predecessor) — is fading at a critical time for Italy.

While a string of successful government bond auctions has eased funding pressures, domestic banks have had to pick up the slack from foreign investors, who have yet to return to Italy’s debt market in a meaningful way. With much larger financing needs than Spain, Italy - which is slightly less than a quarter of the way through its bond issuance target for this year and plans to sell some €90bn in the second quarter alone - is even more reliant on continued domestic bank-buying at auctions.

More pain in Spain

Recent price action suggests investors are more worried about Spain. Since it has to contend with the double whammy of public and private sector deleveraging, and its banking sector has yet to purge the excesses of the boom years, Spain’s borrowing costs ought to be higher than Italy’s. A poorly received bond auction on April 4 revealed the extent to which demand from domestic banks is waning. The brutal budget cuts unveiled last month have only served to spook the markets further.

Spain is caught in a pernicious circle in which the weakness of its public finances, the fragility of its banks and the scale of the downturn are all feeding on each other. While Italy has won back some credibility, Spain is steadily losing it — not because it has been shirking reforms, but because investors increasingly perceive excessive austerity as unfeasible and counter-productive. Enforcing fiscal discipline in Spain’s autonomous communities has already proved extremely difficult while the fiscal contraction is adding to the woes of Spain’s undercapitalised banking sector.

The renewed pressure on Italian spreads is equally, if not more, alarming and could be a foretaste of things to come. Contagion is once again rearing its ugly head. There is still insufficient differentiation between Spain and Italy even though the former’s problems are generally acknowledged to be more acute. Indeed, in many ways, it is Italy that is now the country to watch.

The eurozone crisis is flaring up again. The self-fufilling panic of the kind that gripped the markets at the end of last year is unlikely to return. In its place there will be risk aversion of varying degrees of intensity, somewhat akin to the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM) crises in the first half of the decade prior to the launch of the euro. Then, as now, spreads were large and fluctuated considerably as investors fretted about economic divergences. Not surprisingly, Spain and Italy were among the countries caught up in the ERM debacle. Plus ça change.

Nicholas Spiro is managing director of Spiro Sovereign Strategy, a specialist consultancy in sovereign credit risk.

Spiro Sovereign Strategy

9 Devonshire Square

London, EC2M 4YF UK

T/F: 44 (0) 20 7084 6375

E-mail: info@spiro-strategy.com

www.spiro-strategy.com