Ideas are swirling among European Union policymakers about how to use €170bn of cash belonging to the Bank of Russia, which has been frozen at Euroclear.

Already, the EU uses interest earned on the cash interest and matured principal generated by the central bank’s frozen assets to pay down a $50bn loan the G7 made to Ukraine last year.

Politicians are now talking seriously of using the principal sum to aid Ukraine — either militarily, or to finance its reconstruction. The US has urged them to do so.

The idea is certainly tempting. By invading Ukraine since 2014, and especially since 2022, Russia’s president Vladimir Putin has shown complete disregard for international law and contempt for the lives and wellbeing of Ukrainians — not to mention Russia’s own citizens.

To reconstruct and rehabilitate Ukraine could cost over $500bn, the World Bank estimated in February. Research by a Moscow law firm in July found that the Russian state had also seized some $50bn of Western corporate assets since 2022, Reuters reported.

From the point of view of natural justice, confiscating Russia’s money and using it to help Ukraine seems absolutely fair.

That does not make it right or wise.

Dire precedent

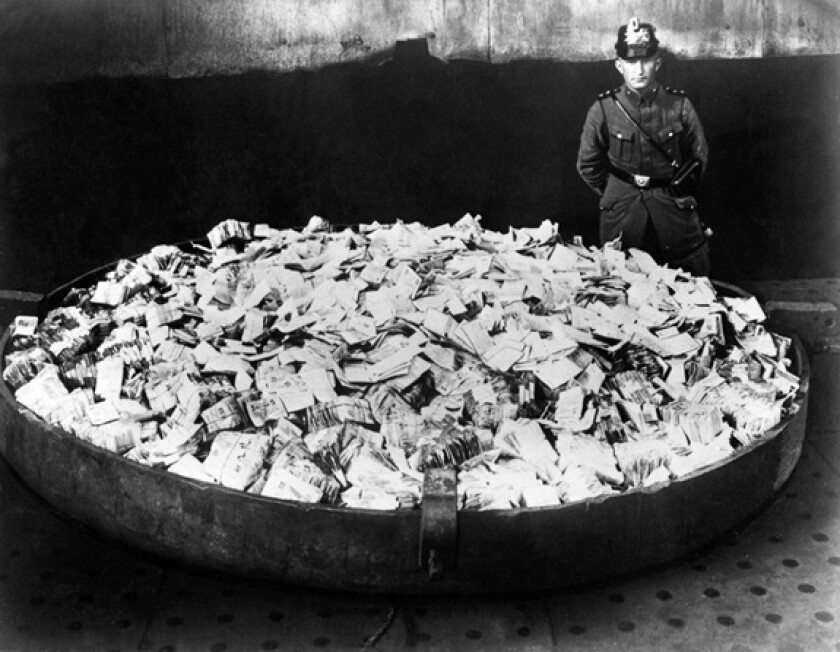

As many debating this issue seem to have forgotten, the financial reparations imposed on Germany after the First World War are widely believed to have generated resentment among Germans and hatred of the Allies, partly because they contributed to economic stress leading to hyperinflation (pictured above).

This was easily exploited by the Nazis, fuelling their drive to launch a new war. Reparations were only one factor, but they were a factor.

Two countries that have fought in the past can sometimes bury the hatchet and begin to get along. But if there is a lasting grudge, it is much more difficult.

If the €194bn of Bank of Russia assets were taken away by the West, it would be certain to create such spite.

Of course, Ukrainians would have much greater reason to resent Russia, which has devastated their country — as Germany did northern France in 1914-18. But many in Russia would not acknowledge that.

On the sidelines

And there is a huge difference between the Russia-Ukraine situation and the Versailles peace treaty. Germany then had sued for peace and the Allies could impose terms.

Russia and Ukraine are still fighting, no one knows when or how the war will end — and the EU and US are not combatants.

The EU can certainly keep hold of Russia’s assets while the fighting continues, and use them as a bargaining chip in negotiations. Withholding them after a peace agreement until Russia fulfils conditions might work.

But there is no way of knowing now how strong the EU’s hand will be in future, or what kind of deals may need to be struck to achieve peace on the best terms possible.

Tread warily

Some of the schemes being considered might be viable, such as investing the assets in higher yielding instruments to generate more interest.

But the EU forcibly borrowing the money to spend on Ukraine is dangerous, creating at best Russian anger against the Union. And how would it be repaid?

Above all, any kind of permanent or irreversible seizure is a terrible idea. Ursula von der Leyen, European Commission president, glibly said last week, according to the Financial Times, that ‘reparation loans’ need only be repaid if Russia agreed to pay reparations to Ukraine directly.

Such a policy, if enacted, would be seen in Russia as tantamount to theft, giving it a cause for future war — when the EU has not even had the stomach to fight this one.

The only hope for peace in Europe, long term, is that one day Russia will have a more benign regime, willing to coexist with its neighbours. That can only happen if some people in Russia actually like the West.

However fair it may seem, tying our hands now to a policy sure to elicit hatred would be savage folly.