Japan, as prime minister Shinzo Abe likes to say, is “back” – meaning that it is back in the game as a global economic and political power after two decades of stagnation and deflation, and that it is raising its profile again after sliding behind the US and China to become the world’s third-largest economy.

To some extent, Abe’s boast is justified. Since he led his Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) back to power in a landslide lower house electoral victory at the end of last year (and then to an upper house rout of the opposition in July), economic and other indicators have been pointing North. Japan’s gross domestic product is expanding at a healthy clip, and the growth rate for fiscal 2013/14 is expected to reach 2.8% – ahead of the US and leaving a still sickly eurozone at the starting gate. Deflation is on the point of ending, the Tokyo stock market is rising, and the yen is – beneficially for Japan, where exporters have complained for years about the strong currency hindering their efforts – falling.

More important for Abe, who sees himself as national morale-restoring figure, confidence is growing, with market business and consumer psychology noticeably stronger, while Tokyo’s success in winning the right to host the prestigious and hopefully lucrative 2020 Olympic Games has many Japanese walking on air.

The estimated 3 trillion yen or so of infrastructure spending that hosting the Olympics will require over the next few years is more than a drop in the ocean, even for a 500 trillion yen economy such as Japan’s; business activity as well as tourism could pick up sharply, analysts say.

Japan’s diplomatic profile is rising too. The globe-trotting Abe, shedding the sickly and ineffective image he earned in his brief stint as prime minister in 2006–7, tours areas of the world ranging from eastern Europe to the Middle East drumming up business for Japan while winning friends and influencing people.

“Abe is Japan’s best salesperson since [former prime minister Junichiro] Koizumi,” says Jesper Koll, director of research at JP Morgan in Tokyo.” When he travels overseas he has top level CEOs in tow, and they have a programme to export 30 trillion yen of infrastructure projects.”

But how much credit for Japan’s partial recovery from a “lost decade” can be ascribed to “Abenomics”– a set of policies to which the scion of a political dynasty (his grandfather was also a prime minister) has willingly lent his name – and how much of Abenomics is the invention of Abe himself?

“The combination of public and private demand and the different staging of the demand patterns is working very well since Abe took office at the end of last year,” Koll says. But some improvements were already underway, and Abe has been “lucky” to capitalize on them.

“GAIATSU”

Abenomics is a combination of present actions and future promises and, while the first part is already very much in evidence with aggressive monetary and fiscal policies being implemented in Japan, the second part, that consisting of structural economic reforms, has yet to be translated into action.

“Abe has not announced any significant new structural reforms, other than getting Japan involved in Trans-Pacific Partnership [TPP] negotiations,” says former Goldman Sachs (Asia) vice-president Kenneth Courtis. The TPP could be a “long-term plus” for Japan, “but the impact is still well into the future”, he says.

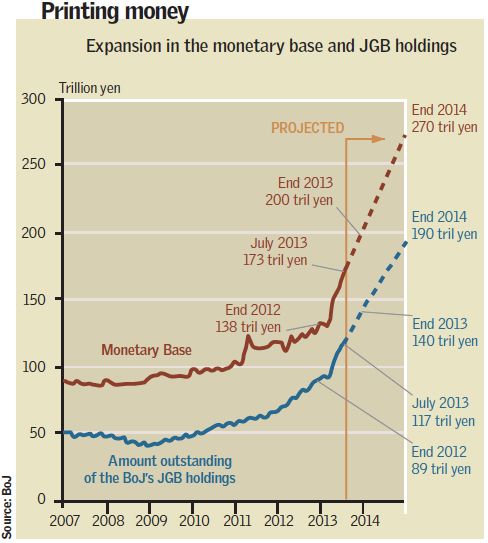

The first two of what Abe (drawing on traditional archery images popular in Japan) calls the “three arrows” of Abenomics are in full flight. The Bank of Japan’s announcement in April that it planned to double the monetary base within two years left even the US Fed looking somewhat lame.

The aim was to shift the Japanese economy out of chronic deflation, to achieve 2% annual consumer price inflation within around two years and to assist with the Abe administration’s aim of raising Japan’s annual real GDP growth rate to 2% or more within a similar time frame.

Testament to the success of this part of Abenomics (which some argue should be called Kurodanomics after the Bank of Japan’s, BoJ, new governor Haruhiko Kuroda) is the fact that by September deflation was giving way to mild inflation, while the yen had dropped by some 20% in value, boosting Japanese exports in the process. Yen depreciation is also raising imports costs, especially those of fossil fuels, which Japan is importing in vast quantities in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear meltdown and subsequent idling of most of the country’s nuclear reactors. Huge import costs in turn feed into inflation.

|

Abe’s second arrow (fiscal measures worth 20 trillion yen by way of a supplementary budget and other government measures) is also contributing to three consecutive quarters of economic expansion. But the third arrow – a strategy for promoting growth – is flying too high for many to see. Even former Japanese vice finance minister for international affairs Eisuke Sakakibara still does not know “what the third arrow is”, he tells Emerging Markets. It embraces aims from regulatory and institutional reform to business restructuring and myriad other things. But so far it is longer on ambition than detail.

The TPP could be Abe’s “secret weapon” for achieving a politically difficult opening up and structural reform of Japan’s economy, some suggest. The TPP – a group of one dozen Asia-Pacific nations led by the US – requires eventual abolition of all tariffs and most business barriers among members. Japanese governments have found it easier to sell painful economic reforms (such as those Japan will require to make in areas ranging from agricultural access to health services under the terms of the TPP) if these reforms can be presented as due to external pressure, or “gaiatsu”.

But there is no denying the fact that, whoever should take the credit for Abenomics – people such as former Yale University professor Koichi Hamada (now one of Abe’s close economic advisers) or the BoJ’s Kuroda and others – the Japanese economy and psyche are getting a boost. “There is a sense of dynamism [in Japan] that we have not seen for some years,” says former Goldman investment banker Courtis. “Whether that dynamism is transferred into real economic performance is another question, but optimism and dynamism are necessary to making things change.”

FAST GROWTH

Sakakibara too is upbeat. “Japan is in the process of recovery.” he says. “It had a negative rate of growth in 2011 because of the earthquake and tsunami, and it is still in the process of recovering from that. The growth rate for 2012 was 2%, and the rate for 2013 will probably exceed 2%.” That, he notes “is a fairly strong rate of growth for a mature economy such as Japan’s, and I would say that among the developed countries – US, Japan and Europe – Japan will probably achieve the highest rate of growth in 2013.” This is mainly due to monetary and fiscal stimulus, he adds.

Some experts caution, however, against over-reliance on either of these stimuli. Courtis, for example, notes that Japan’s recovery is heavily dependent upon devaluation of the yen, zero interest rates and a big fiscal deficit. “Take these away, and the economy would be doing really poorly.” The BoJ’s quantitative monetary easing (QE) is bigger in balance sheet terms than that of the US Federal Reserve or the European Central Bank’s expansion of its balance sheet. Charles Dallara, former head of the Institute of International Finance in Washington, says that none of the three central banks should over-rely on QE policies.

QE has a role to play in averting financial crises, spurring economic activity and helping labour markets. “But I think there are times when governments use it as a bit of an excuse to avoid coming to grips with their own responsibilities” in economic restructuring, Dallara tells Emerging Markets.

Japan’s fiscal debt is meanwhile of greater size even than its QE operations. At some 240% of GDP, the government’s outstanding gross debt is by far the highest in the OECD and growing rapidly. “Japan’s government cannot continue increasing the debt by 10% of GDP a year,” Courtis warns.

Fiscal restructuring is due to begin next April, when Japan’s national consumption tax is scheduled to be raised from 5% to 8% and then by a further increment to 10% in October 2015. At that time, the Japanese economy “is going to be severely tested”, adds Courtis. He worries that “long-term demand will stay weak in Japan even if Abenomics is successful. With the population contracting every year, unless the ones who remain increase their consumption enough to offset the fall in consumption by those who die, then the economy will contract. It would take 15–20 million young immigrants over the next 15 years to change these deep trends, and that is not going to happen.” Meanwhile, an increasing share of Japanese firms’ output is likely to shift overseas, exacerbating the contractionary trend in the economy, Courtis says.

But JP Morgan’s Koll sees cause for greater optimism. Japan has a positive “credit cycle” now for the first time in 20 years, with bank lending picking up not only as a result of Japanese firms investing overseas but also because Japanese individuals are borrowing, he points out. For the first time in their working lives, many younger Japanese are seeing job security improve, and they are taking out mortgages in sign of confidence in the future. “Japan’s labour market is actually tightening, and you now have demand for labour-intensive services growing,” Koll adds.

Unemployment has fallen to 3.8% and is set to fall further. Labour demand is coming not from Japan’s traditional manufacturing sector but “from the individual services sector – merchandizing, logistics and healthcare,” he says. Japan is entering “an endogenous, domestic demand-based recovery”.