The Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing exercises saw billions of dollars flow out of the US and into emerging markets in search of higher yields. Now investors are watching to see whether the Bank of Japan’s (BoJ) mega monetary easing will have a similar impact on emerging market asset prices.

The BoJ’s easing of money flows within Japan and to the outside world has the potential to have a very big impact. The central bank will double the size of the monetary base to 270 trillion yen by the end of 2014, including a doubling of its holdings of government bonds to 190 trillion yen.

As a proportion of GDP, that is bigger than the Federal Reserve’s easing and, given the impact that dollar outflows from the US had in pushing up emerging market asset prices, Japan’s easing could, some speculate, somewhat compensate for Fed tightening as tapering talk turns into action further down the road.

“Japanese monetary expansion [when set against] US contraction and European recession will tend to expand the position of Japanese finance in the rest of the world,” former deputy finance minister for international affairs Eisuke Sakakibara tells Emerging Markets. But the pattern of Japanese

financial flows is likely to differ greatly from that of the US and Europe, Sakakibara and others say. Japanese outflows will mainly take the form of foreign direct investment by business firms rather than portfolio outflows, to both advanced and emerging markets.

“Not a week goes by when you do not have a Japanese manufacturer committing to building a new factory or to some M&A activity,” says Jesper Koll, head of research at JP Morgan in Tokyo. Activity “died down a little over the last couple of months but it is going to be picking up again,” he adds.

Global direct investment and M&A outflows from Japan reached $112 billion or 11 trillion yen last year at a time when overall global flows were declining. Japanese outflows dropped off in the first half of 2013, partly as a result of yen depreciation, although that also reflected the fact that some major outward investments were made in 2012.

Japan is the second-largest source of outward foreign direct investment (FDI) in the world nowadays, behind the US (from where outflows totalled $350 billion in 2012), although China leap-frogged others to become the third largest last year and some believe that it could soon overtake Japan. The major destinations for Japanese outward FDI initially were South Korea and Taiwan. But as labour costs in these economies rose, Japanese FDI shifted to the Association of South-east Asian Nations (Asean) economies, and that trend is increasing now as a result of Japan’s tensions with China. Flows to India are also rising.

|

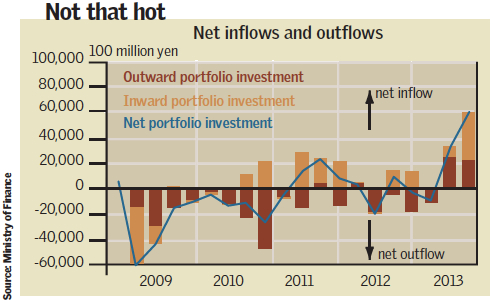

INFLOWS, ACTUALLY By contrast, portfolio outflows from Japan turned to net inflows of some 10 trillion yen in the first half of this year, according to ministry of finance data. Rather than picking up the slack in emerging markets created by US tapering, Japanese portfolio investors appear to have taken fright at the drop in

emerging market asset prices. Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda told Emerging Markets earlier this year that portfolio outflows from Japan since the central bank’s mega easing measures had been headed mainly toward advanced economies; another BoJ official said in September that this trend continues.

“The direct trigger for the emerging market slowdown was [Federal Reserve] tapering, but if you look closely at the emerging markets, they may have been in some kind of bubble situation, and that bubble has now burst,” says Sakakibara. “Japanese institutional investors are still very conservative, and rightly so probably,” he notes. “They should not take too much risk. If they invest in the Japanese Government Bond [JGP] market they can get 1% annual return, and with Japan’s deflation that’s not bad.”

JP Morgan’s Koll describes Japanese institutional portfolio investments to the outside world as being virtually “non-existent” in relation to the same side of the Japanese economy. Heavier outflows “will take much more time [to materialize] because at the end of the day for a pension fund or insurance company to take on more risk at a time when your domestic asset base is actually growing” does not make sense, he suggests. “It is a tricky business, with huge headwinds, because of the [ageing] demographics in Japan. So, I am not holding my breath for any ‘great recycling’, plus Japan already is a net importer of capital, as you can see by looking at the equity market.”

Japan is running a big trade deficit nowadays because of its heavy dependence on imported fuels in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear accident in 2011 and the subsequent idling of most nuclear reactors in the country. This implies capital imports on the current account to fund the trade deficit. “So this idea that Japan will become a big creditor country to the rest of the world is not going to happen,” says Koll.