Despite roaring economic growth, much of Asia continues to grapple with an infrastructure deficit. While GDP, industrial output and consumption have soared across the region over the past decade, power, water and transport systems have struggled to keep pace.

Since Asia’s 1997 financial crisis, the region’s infrastructure needs have almost exclusively been met by the state. But the requirements are now so large and the demand for quality so great that the way Asian infrastructure is being financed is undergoing a profound change.

Experts agree that the opportunities for private capital investment into the region’s infrastructure are set to rise exponentially over the next 10 years, and many governments are now actively courting private involvement. A recent report by global consultancy McKinsey estimated that over the next 10 years, $1 trillion of the projected $8 trillion in infrastructure projects in the region will be open to private investors under public-private partnerships (PPPs).

But despite the clear need and obvious opportunities for private involvement in Asian infrastructure, regulatory risks continue to hold back private capital from reaching its full potential in the region.

QUALITY AND QUANTITY

The causes of this increased need for private-sector infrastructure investment vary from country to country, but can be broadly grouped under two categories: insufficient funds and a huge increase in demand for quality infrastructure.

Demand for new infrastructure will drive much of the new investment. According to the McKinsey report, India, for example, faces a 16–20% gap between its current electricity capacity and its peak demand.

According to Ali Naqvi, head of infrastructure for East Asia and Pacific at IFC, over the next five years Asian governments will spend between 1% and 3% of their GDP on infrastructure investment. But he argues that, given the region’s growth targets and development needs, infrastructure spending should be between 6% and 7%. “The infrastructure needs in Asia are huge but the funding gap is getting bigger,” he says. “And only part of Asia’s infrastructure needs is being financed.”

Asia doesn’t just need more money for infrastructure – it needs better quality, including clean water, uninterrupted electricity, urban transportation systems, highways. “Because of the rate of economic growth, many countries have reached a point in real incomes which creates an exponential rise in demand for infrastructure, and within this, the quality dimension is key,” says Kamran Khan, programme director for the World Bank in Singapore.

The funding gap together with the demand for quality point to opportunities for private-sector involvement in the region’s infrastructure finance. McKinsey estimates that as infrastructure spending rises from 2–4% of GDP to 5–7%, up to half of this increase needs to come from private-sector and foreign sources.

OLD MODELS, NEW MODELS

Prior to the Asian financial crisis, there was significant private-sector involvement in infrastructure investment in the region. But many private-sector investors lost money during and in the immediate aftermath of the crisis, especially as governments around the region reneged on contractual obligations to pay and maintain tariff regimes. Since then, strong economic growth, high domestic savings and budget surpluses have meant that infrastructure investment has largely come out of government or domestic bank budgets.

“For much of the 1990s, south-east Asia was the infrastructure finance capital of the world,” says Ashley Wilkins, head of global finance for Asia-Pacific at Société Générale. “But after the Asian financial crisis in 1998, the sector slowed down markedly, and most of the funding for infrastructure came from governments and public sources of finance. And that is where it has stayed until very recently.”

Asia is still growing strongly, and governments continue to have access to large volumes of internally generated cash flow from which to invest in infrastructure. But the needs are now so large and the demand for quality so great that governments are increasingly unable – or unwilling – to cover the costs alone.

According to Frank Kwok, executive director at Macquarie in Hong Kong, China and India’s infrastructure investment needs will total $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years alone, of which he estimates that as much as one-third will come from private-sector sources.

Australian lender Macquarie is very much alive to this opportunity. It already has an existing $1.2 billion joint venture in India with State Bank of India and a toll road specific fund in Korea. It is also launching a China-focused infrastructure fund in a joint venture with state-owned financial services group China Everbright.

CAN'T PAY, DON'T WANT TO PAY

In the case of larger Asian economies including China, the increased emphasis on private-sector investment is not down to a lack of state capital.

Instead, the way infrastructure was financed in China in the past – through local government borrowing, land sales and central government fiscal transfers – has exacerbated economic problems such as inflation and local corruption that the central government is now seeking to address. The National Development and Reform Commission in China now publishes a list of “encouraged sectors” in which it is trying to get foreign and private-sector capital to invest. These include roads, power, ports, airports, water and railways.

In contrast, countries in south-east Asia are equally determined to attract private-sector money into infrastructure, although this is largely due to budget restraints rather than a fundamental desire to change the model.

The new government in the Philippines has been particularly active when it comes to establishing a framework for attracting private-sector finance. One of the first acts of President Benigno Aquino’s government was to establish a PPP framework.

“In the development of infrastructure, the private sector must be induced to make the investments,” President Aquino told a specially convened conference outlining the country’s PPP opportunities to 600 international and local investors in Manila in November 2010. “For that to happen, we know the rules must be fair, clear and equally applied to all. The problem is that for the longest time, those rules have been less than fair, far from clear and not always applicable to all.”

|

MINIMIZING REGULATORY RISK

This frank assessment of the difficulties in attracting private infrastructure investment could be applied equally to many other countries in the region. While it is clear that there is a huge demand for new infrastructure, regulatory risk has long proved a stumbling block. Finding ways to get around this is therefore central to mobilizing greater private investment.

In the Philippines, for instance, the new PPP legislation provides guarantees for contractors and concessionaires against regulatory risk. In Indonesia, the government has been working with the World Bank to establish an infrastructure guarantee fund that will recompense investors if ministries don’t pay up or if losses are incurred from legal or regulatory decisions.

“You cannot deal with a government where the right hand is offering a handshake and where the left hand is trying to pick your pocket,” said Aquino. “Infrastructure can only be paid for from user fees or taxes. When government commits to allow investors to earn their return from user fees, it is important that the commitment be reliable and enforceable.”

The fact that governments are both actively courting private investment and are willing to offer guarantees and concessions represents a major change in terms

of Asia’s infrastructure financing model, a change that the private sector has acknowledged.

“A major risk with investment in infrastructure, even in developed markets, is that you are often at the behest of governments,” says Macquarie’s Kwok. “But now Asian governments are being very explicit about their goals to encourage private-sector investment, and that is a big change.”

ENTER THE MULTILATERALS

Much of the work to help governments manage this shift is being done by development banks and other multilateral institutions. The World Bank, for instance, has established an Infrastructure Finance Centre of Excellence in Singapore, which will provide governments around the region with advice on such things as how to structure tender documents, the correct way to draft concession agreements and what to expect from financial advisers and providers.

“We discovered very quickly that there is a high need for this kind of advice,” says the World Bank’s Khan, who was instrumental in setting up the centre. “We concentrate on actual transactions, so when a country wants to pass a new PPP law, or is looking to do a demonstration project, that is where we come in.”

So far three such projects have come to light: a master plan for transport in the Vietnamese city of Danang, a water supply and treatment PPP in Indonesia, and a toll road deal in Chongqing in China.

ONE SIZE DOESN'T FIT ALL

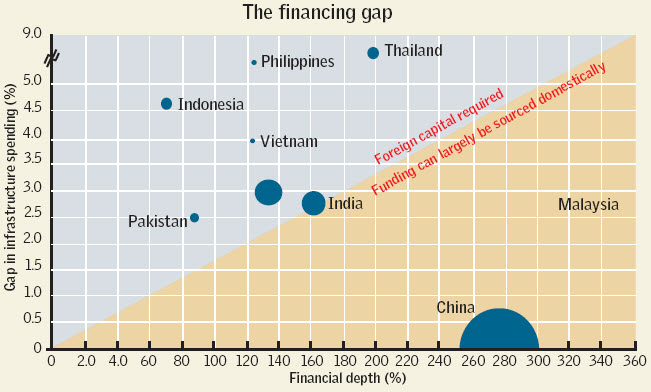

What is clear is that one size will not fit all in the new paradigm for Asian infrastructure finance. According to McKinsey, there is a divide between those countries with sufficient internal resources to pay for their own infrastructure, such as China and Malaysia, and those that do not, such as Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines and Thailand. Even so, both offer opportunities for the private sector.

In more developed countries, existing infrastructure could be sold to infrastructure funds or pension funds, which are attracted to high-quality, cash-generating assets with a predictable and stable return profile. For instance, there are 60,000km of toll roads already built in China, and these will provide a ready source of income to finance new toll road development. Kwok and the team at Macquarie believe this model could finance the creation of 20,000km of new roads in the country over the next 10 years.

In other countries, the challenge is to create a regulatory structure that allows private investors to accept the regulatory and legal risks. Infrastructure investment is long term, but it also needs to be somewhat flexible in fast growing and changing markets such as those in south-east Asia.

Getting the documentation right is the first step in attracting the capital that Asia needs to meet its citizens’ infrastructure aspirations. If and when this happens, the hope is that private capital will follow, not least given the scale of the opportunity at hand.