That Asia is the engine of the global economic recovery is, by now, undisputed. The region’s rebound following the global crisis was almost as dramatic as the preceding economic cataclysm itself.

The ADB forecasts regional GDP growth of 7.8% this year, slightly down from the 9% reached in 2010, but evidence nonetheless of what the bank calls “a firm recovery” from the global crisis.

But in recent months, fears have emerged that Asia’s gravity-defying growth story could come unstuck as inflation begins to take hold across the region – and as policymakers scramble, in some cases belatedly, to respond. Food and energy price shocks, shrinking output gaps, growing evidence of overheating and a glut of domestic liquidity have all added to the concerns.

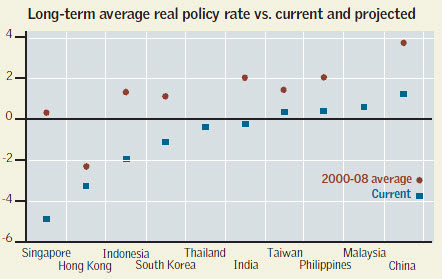

Authorities have tightened monetary policy across the region – whether through interest rates or price controls, administrative and macro-prudential measures – in a bid to contain headline and asset prices, while anchoring inflation expectations. But inflation – both headline and core measures – continues to rise across much of emerging Asia. With interest rates well below historical averages, the worry now is that the policy response has fallen short.

Moreover inflationary pressures are ever more driven by internal rather than external factors, analysts note, increasing the burden on central banks even if headline inflation rates begin to fall this year, as many expect.

EARLY WARNING

Consumer prices began their ascent in Asia late last summer, with sustained CPI increases in both net commodity importing countries such as South Korea and China, and in net commodity exporters such as Malaysia and Indonesia.

Much of the surge in prices was driven by food supply shocks: food inflation is tracking in double digits in many major Asian economies, though non-food inflation levels have remained significantly lower. But with food prices comprising more than 40% of CPI baskets in the Philippines, India, Sri Lanka, Cambodia and Pakistan, and more than 30% in most other emerging Asian economies, the impact on headline inflation numbers has been severe.

Meanwhile energy inflation has emerged as a significant risk for much of the region, as ongoing political unrest in the oil-exporting Middle East has driven up global energy prices. This is so despite the fact that many Asian economies are net oil importers and have complex end-user energy price controls and subsidies in place, while many rely on energy-intensive heavy industry for a sizeable chunk of their industrial output.

“Rising inflation in the region is obviously a risk right now,” says Vishnu Varathan, Asian economist at research firm Capital Economics. While inflation was largely driven by food at the beginning of the year, oil has now replaced it, he says. “High commodity prices most adversely impact Asia relative to other emerging markets; Asia gets the short end of the stick when oil prices go up.”

SEEPING TO THE CORE

For now, the consensus is that food inflation will peak in the coming months before moderating in the latter half of the year. But this assumes no further supply shocks – a significant risk given tight stocks of key commodities. Meanwhile rising global energy prices have yet to show up in consumer or producer inflation levels across most of the region.

Michael Spencer, Deutsche Bank’s chief Asia-Pacific economist, says that increased planting of major food crops will lead to a decline in food price inflation from this summer. “I expect deflation in food prices a year later,” he says.

But the worry is that inflation in Asia may be turning into a domestic, demand-driven problem rather than an external, supply-driven phenomenon.

“The media has very much focused on rising food and energy prices, but this has served as a bit of a red herring given the strength of underlying demand in Asia,” says Tai Hui, head of south-east Asian research at Standard Chartered.

Demand-driven inflation, he says, will require a sustained policy response, even if food and energy prices begin to fall. “Assuming food and energy prices behave themselves in the second half of the year, policymakers won’t have an excuse anymore,” says Hui. “They’ve been saying that inflation is external and that they can’t do anything about it. If these external pressures fade, they will have to face demand-driven inflation head on.”

The increasingly domestic, structural nature of inflation across the region stands in sharp contrast to inflationary problems faced by policymakers in other regions, says Varathan. “The West still has huge capacity overhang, and employment hasn’t picked up. In emerging Asia, labour market conditions have tightened, and output gaps have closed up considerably.”

VARIED APPROACH

Against this backdrop, the actions of central banks have come under increasing scrutiny. With early price pressures arising from rising food prices, many policymakers initially shunned interest rate rises in favour of speeding up domestic food supplies, or by imposing food price controls or subsidies for consumers and farmers. The reluctance to raise rates was exacerbated by fears of courting hot money.

Most economies have since begun to hike rates while reining in credit and liquidity. But the speed of the policy response has varied significantly across the region.

India, Malaysia and Thailand began to raise interest rates from the middle of last year. China raised the base rate last October and has raised rates three times since, most recently a 25 basis-point hike on April 6, while also hiking the reserve requirement ratio for banks four times this year to a record 20.5%.

“Chinese policymakers have responded pretty quickly and in a rational way,” says Andy Rothman, China macro strategist at CLSA, an Asia-focused brokerage firm.

|

TOO LITTLE, TOO LATE

Other nations have been slower to act. Both the Philippines and Indonesia have only raised rates once since the onset of the global financial crisis, despite mounting evidence of headline and core inflation in both countries. Indonesia is one economy widely seen as being behind the curve in this respect. Says Spencer: “It was clear late last year that inflation was going to rise faster than they expected, and they got caught on the wrong foot. We’ve had one rate hike, but we need more.” He adds: “Bank Indonesia (BI) has a credibility problem.”

BI’s decision to hold off on a further rate rise at their April 12 meeting has also been criticized. “Their hesitation isn’t helping,” says Varathan.

Vietnam, too, has come under fire for responding slowly to price pressures. Consumer inflation rose to 13.9% in March, with food price inflation tracking at 17% and core inflation also tracking in double digits. Standard Chartered’s Hui notes that although prices started to rise last year “not only did policymakers not raise rates, they actually cut them to boost growth.” He adds: “They got to a point where their currency was under so much selling pressure that they were forced to raise interest rates.”

But he notes that policymakers are finally on the right track in tackling inflation. “The patient has started to be given the right medicine, but it will take time to recover.”

Then there is India. Its central bank began hiking policy rates early in 2010 and has tightened by 200 basis points this year alone. Yet headline and core inflation have remained stubbornly high, with WPI inflation rising to 8.98% year-on-year in March, and non-food manufacturing prices accelerating to 6.21%.

Deutsche Bank’s Spencer believes the Indian government failed to acknowledge domestic drivers behind inflation soon enough and that the policy response has been inadequate. He says policy tightening has been extremely mild if looked at in terms of real interest rates.

“For too long, the government believed that inflation was purely due to supply shocks, even though inflation was already in double digits,” says Spencer. “Unlike the rest of Asia, non-food inflation is actually rising faster than food inflation. It’s a classic overheating story.” He says three or four hikes over the next few months will be insufficient: “Monetary policy needs to do a lot more than that.”

The government’s overly expansionary fiscal policy, rather than the RBI’s [Reserve Bank of India] “commendable” policy response, is to blame for current high inflation rates, says Varathan, as it has created excess demand and excess liquidity.

“Fiscal policy on the whole remains a whole lot more expansionary than it needs to be, and that means that the RBI has had to shoulder more of the burden in terms of tightening,” he says. “There is a need for fiscal authorities to pull their weight as well.”

Commodity exporters in the region, such as Malaysia and Indonesia, have also come under fire for failing to make the most of recent windfalls, due to record global commodity prices, by introducing reforms aimed at using commodity export revenues to implement long-term structural reforms.

“Malaysia needs to make better use of its commodity income,” says Hui. “The government has the desire to move in that direction, but implementation is a much longer horizon.” He sees Indonesia as making genuine strides to use commodity export revenue to improve infrastructure and tap domestic demand, but cautions that this will be a long process. In both countries, economists warn that a failure to enact fiscal reform could increase the eventual burden on the monetary front.

Still, despite heightened concerns about the speed and scale of the inflation response in some countries, analysts are largely constructive on the region as a whole. “You can’t just jump from where we are to where we need to be right away,” says Hui. “Policymakers are still in the process of tightening interest rates further, and they are by no means done. [But] they’re doing it in a relatively gradual manner.”

Says Spencer: “Monetary policy is still too loose, but if they continue raising rates at the current pace, another six rate hikes over the next 12 months will get us where we need to be.”

OTHER MEASURES

Central banks across emerging markets have also resorted in recent months to capital controls and other so-called macro-prudential measures to temper credit and liquidity growth and combat inflation. While the official debate over the efficacy of such unorthodox measures gathers pace, experts are warning that they must not come at the expense of traditional policy tools, specifically headline interest rates.

“They are no substitute for policy rates, but they might lessen the scale of the rate hikes that we need to see,” says Varathan.

Administrative and macro-prudential measures, used in conjunction with interest rate hikes, could nevertheless be the right tools for tackling food and energy inflation. Says Hui: “Hiking interest rates doesn’t force people to eat less or consume less energy.”

In addition, a number of south-east Asian economies, in particular Indonesia, have justified their slow response on the interest rate front by enacting faster currency appreciation, arguing that adjusting exchange rates will be the most effective way to counter import inflation.

While currency appreciation has had some effect in moderating the impact of higher global commodity prices on domestic inflation in some countries, and economists believe that faster appreciation in other regional economies that have shown a greater reluctance to adjust their exchange rates, such as China, would aid in the inflation fighting process, analysts warn that exchange rates are only one part of an effective policy response.

“Allowing currencies to appreciate is a complement to everything else policymakers are doing, but not a substitute for the need to hike policy rates,” says Varathan.

CALLING IT RIGHT

If, as many economists expect, food and energy prices begin to ease from the second half of this year, immediate headline inflation pressure across much of the region should moderate.

But with signs that the drivers of inflation are now domestic as well as external, the hope is that politicians in particular won’t take an easing of food and energy price inflation as a signal to press for an end to the current tightening process.

“My base case is that a year from now, people will be surprised at how low inflation is, but I hope that central banks keep raising interest rates at a slow pace,” says Spencer. “The danger is that they will pause, headline inflation will bounce back up, and we will be back where we were six months ago.”

Policy will need to be tightened further even if global food and energy prices begin to moderate in the coming months, says Varathan. But authorities may be reluctant to hike rates, not least given persistent external vulnerabilities, including a worsening eurozone debt crisis and mounting uncertainty over fiscal and monetary policy in the US.

“The risk that policymakers drag their feet for too long and succumb to the temptation of not moving is a real one, but by and large the risk is mitigated,” says Hui. “Even though some policymakers continue to drag their feet, they are at least moving.”

Central banks will remain cautious about over-tightening and will continue to “cross the river by feeling the stones”, he says.

But central banks may nevertheless have realized they need to tighten further despite the uncertain global outlook: China and India, for example, both hiked rates and reserve requirement ratios the same week as Japan’s earthquake and tsunami.

“Central banks still see themselves as less than halfway along the tightening road, so unless there is a catastrophic global slowdown, they will continue to tighten,” says Hui.

HEFTY WAGER

Still, the likelihood that the region’s central banks will tighten policy too much and thereby trigger a sharp growth slowdown remains small, analysts say. Many of the region’s economies are operating at or above capacities, so slightly slower growth rates would be welcome in many cases. Moreover, continued productivity gains should help to offset any negative impact on growth from tightening.

“There is a risk of over-tightening. It’s always a possibility, but the risk is very low,” says Hui.

Despite headline wage disputes at factories in China and across parts of south-east Asia, there is also little evidence that inflation and negative real interest rates have led to significantly increased wage demands as yet, or that policymakers are yet facing wage-price spirals.

But if authorities halt the current tightening process too soon, or if food and energy prices fail to ease as expected later this year, the risks would rise significantly of monetary tightening of an order that could have a material impact on growth.

By maintaining a gradual approach to rate rises, policymakers run the risk of leaving the region’s economies exposed if food or energy prices spike further, says Spencer.

“Policymakers are taking a gamble, but if you think that food prices inflation will start to decline come Q3, as I tend to do, then it’s probably not a bad strategy,” he says. “The gamble is that in six months’ time, food price inflation is 20%.Then we have a real problem.”