|

Parliamentary elections in Kyrgyzstan hold out the prospect of a type of democracy almost unprecedented for post-Soviet central Asia, where the norm is for executive power to be autocratic and the freedoms of speech and assembly are limited. As Emerging Markets went to press, Kyrgyz voters were today set to go to the polls. But whatever the outcome, neither stability nor a real expansion of democracy are guaranteed, given the continuing civil tensions and the disastrous economic setback that resulted from violence that exploded in Osh, southern Kyrgyzstan, in June. Those events have had political repercussions in Uzbekistan, too, where a surge of refugees from Kyrgyzstan exacerbated the authorities’ fears of unrest and repression of dissidents.

The underlying problem is the way that some of central Asia’s economies are skewed towards oil, gas and minerals production and exports. Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, which boast few such natural resources, are falling ever further behind oil- and gas-rich Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan. Uzbekistan has mineral resources, too, but its government has done little to direct revenues to its large, rapidly expanding and mainly rural population.

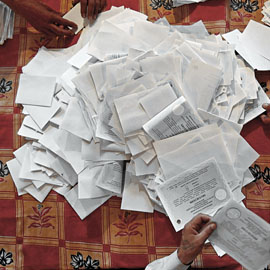

Today’s Kyrgyz elections will be held under a rule limiting the largest party to 65 seats in the 120-seat legislature. Roza Otunbayeva, interim president of Kyrgyzstan, who came to power after the disturbances in April that toppled Kurmanbek Bakiev, has pledged that no state resources will be used to fund electioneering.

But while the elections have triggered an unprecedented interest in politics, there are real fears that wealth and power from the past will skew the results.

In Osh, where 400 died and thousands were driven from their homes in violent clashes in June, mainly between Kyrgyz and Uzbek groups, its mayor Melis Myrzakmatov has been accused of playing on nationalist tensions. UNHCR, the United Nations refugee agency, accuses Myrzakmatov, a former ally of Bakiev, of turning a blind eye to members of the security forces as they targeted, harassed and kidnapped young Uzbek men.

Madeleine Reeves, a researcher of central Asian society at the University of Manchester, says: “In the run-up to the elections we are seeing a politicization of society. People are talking about joining or setting up political parties, and discussion is flourishing.

“But whether that will translate into parliamentary politics is another question. I fear parliament may be dominated by ‘strong men’ parties: many people will find it difficult to see the differences between the parties, with the exception of the Communists.”

Anna Matveeva, associate senior fellow at the London School of Economics, says: “There is a problem: nationalism, and intolerance towards minorities. When Bakiev was in office this got completely out of control, and the new government that took over this year has done little to address it.”

SPILL-OVER EFFECTS

The instability in southern Kyrgyzstan has also heightened tensions in Uzbekistan, according to human rights activists there. The Uzbek authorities organized temporary camps for Kyrgyz refugees, but clamped down determinedly on civil society activists who tried to help. The Human Rights Alliance of Uzbekistan has reported an upsurge of arrests and threats over the summer.

Matveeva says the response to the crisis by Kyrgyzstan’s larger neighbours was mixed. “The isolationist politics of the region came through. Kazakhstan held the chairmanship of the OSCE [Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe] and had to do something – but it had no capacity or desire to, and simply closed its borders. Uzbekistan catered for refugees very well, but nothing more.”

The unrest in Kyrgyzstan has been catastrophic for the economy: GDP grew 16% year-on-year in the first quarter, boosted by strong prices for gold exports, but crashed in the second quarter and is now forecast to contract by 3.5% over the year.

Agriculture (which accounts for 25% of GDP), trade (16% of GDP) and other services, mainly tourism (5% of GDP) were “hard hit by the unrest and the border closures”, says Rika Ishii, principal economist at the EBRD. “Investor confidence has been severely eroded, RGW loan quality of the financial sector has deteriorated significantly, and loan growth is likely to slow down or even contract.”

An alliance of multilaterals – the IMF, ADB, Eurasian Development Bank and EBRD – joined with the EU and the US government in July to put together a $1.1 billion aid package aimed at kick-starting recovery, about half of which will be disbursed this year.

Olivier Descamps, a managing director at the EBRD responsible for its part in the effort, says: “The fact that the government was sufficiently credible to attract aid on that scale – equivalent to 24% of GDP – is not to be ignored.”

The EBRD’s share of the effort is directed, first, at following through on desperately needed municipal infrastructure renewal projects and, second, on strengthening the micro-finance sector, which already accounts for 23% of lending in Kyrgyzstan.

Ishii says that, looking across the whole of central Asia, recovery will depend more than anything on Russia and Kazakhstan – which means, on oil: “Central Asia’s relationship with China is growing, but it’s one-sided. It’s a market for Chinese products but, apart from oil, does not have any significant exports to China.”

“The real determinant is central Asia’s relationship with Russia, not only through trade, but through the large number of migrant workers who work in Russia.”