The IMF’s Christine Lagarde warned last week that rising US rates could trigger a repeat of the 2013 taper tantrum that rocked emerging markets.

Her concerns were referenced a few days later in an RBS analyst report titled “The next credit crisis: Emerging Markets”. The analysts believe a combination of private debt build-up, an upcoming turn in Fed policy, high reliance on external funding and lower commodity prices has made EM corporate and financial debt in dollars and euros vulnerable to a shock. “The EM house,” they said, “is about to catch fire”.

Even without a market manically searching Fed minutes for rate hike auguries, there is every reason to scrutinise emerging market debt closely. Since the taper tantrum of 2013, investors are painfully aware that some EM economies have abused years of plentiful dollar bond funding, and their fundamentals are now the worse for it. But others haven’t, and blanket statements lumping all emerging markets together are fundamentally unhelpful.

First of all, there are plenty of EM debt tropes that are misleading. As the RBS analysts note, EM economies have benefited from continued capital inflows over the past several decades. They report that capital flows and cheap dollar funding have allowed EM corporates and households to borrow over 30% of GDP over the past 7 years. In short, EM private debt has increased. A lot.

But looking at the past few decades, total emerging markets debt — corporate and household credit, public debt and external debt — has risen by 20% of GDP, according to Emerging Advisors Group analysts. The increase in developed markets over the same period on the other hand, was almost 250%.

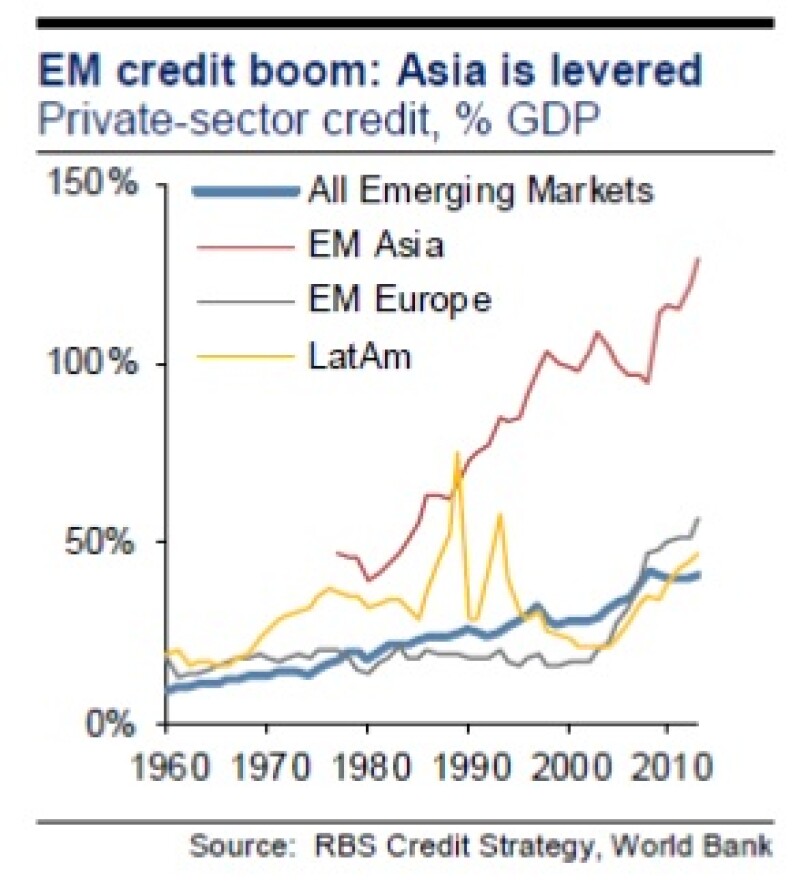

The other point is that looking at EM as one unified market often isn’t that useful. RBS analysts are of course aware of this. In order to represented the EM credit boom they break EM down into constituent regions in the graph below.

What’s immediately apparent is that EM Asia’s credit boom is colossal compared to the other EM regions. Looking at the All Emerging Markets line, the credit boom seems far less severe. And the EM Asia increase — and to a lesser extent the All Emerging Markets increase — is skewed by China.

Emerging Advisors Group's figures look at aggregate debt not private credit, but that measure still includes private sector credit. When they remove China from the aggregate debt equation, total EM debt is still lower now as a percentage of GDP than it was in 2000, and no higher than it was in 1990.

EM currencies, the RBS analysts note, are falling (against the dollar) along with commodity prices. True. But the currencies are falling because the dollar is getting stronger, not because people are concerned about emerging markets. The proof comes from the fact that developed economy currencies have had similarly weak performances, and in many cases EM currencies have done better.

Over the last 12 months only the rouble and the hryvnia failed to outperform the euro, according to Emerging Advisors data. The currencies of Thailand and Kazakhstan have done better against the dollar than sterling over the last 12 months, the same data shows. The Peruvian nuevo sol and Malaysian ringgit have done better the Canadian dollar, and South Africa rand and Indonesia rupiah better than the Australia dollar.

There is also no doubt that commodity prices are falling, but EM is not just a commodity trade. Manufacturing economies in Asia — Philippines and India —emerging Europe — Romania and Poland — and the UAE in the Middle East are all well placed to post decent growth rates. Manufacturing economies should be particularly optimistic given the US recovery, which is what would prompt the rate hike.

Crying crisis

The RBS analysts also list more bond market specific issues — EM firms are now more reliant on dollar-denominated debt, and some EM debt spreads have not widened to compensate for risk. But on average EM corporate spreads still offer value relative to US high yield bonds, which is where many EM investors look for a comparison.

“Some” EM debt valuations may not compensate adequately for risk, but then it would be highly surprising if all firms across the EM spectrum did. Likewise, EM yields and spreads are indeed “below where they could be in a crisis,” but that’s because there isn’t a crisis. Swedish covered bonds are also trading conspicuously lower than where they could be if the Swedish housing bubble bursts.

What of the claim that EM firms find themselves “heavily reliant” on dollar debt “often not hedged against local currency revenues”?

In fact most corporates in the main emerging market indices are either indirectly hedged through a currency peg to the dollar — as in much of the Middle East — derive a good chunk of their revenue from exports — as in Russia — or are sophisticated managers of currency risk — as in Turkey and South Africa.

Of course there are still problem countries where firms are highly vulnerable to another taper tantrum. The RBS analysts are shorting Russian and Brazilian banks and corporates, and Chinese property firms. But Russian corporates and Chinese property firms are not your standard EM credits, because most EM countries are not engaged in a proxy war in Eastern Europe or coming to the end of the greatest period of construction from a single country in human history. Brazil is stuck at zero economic growth and posting the worst fiscal performance for 15 years. India isn’t.