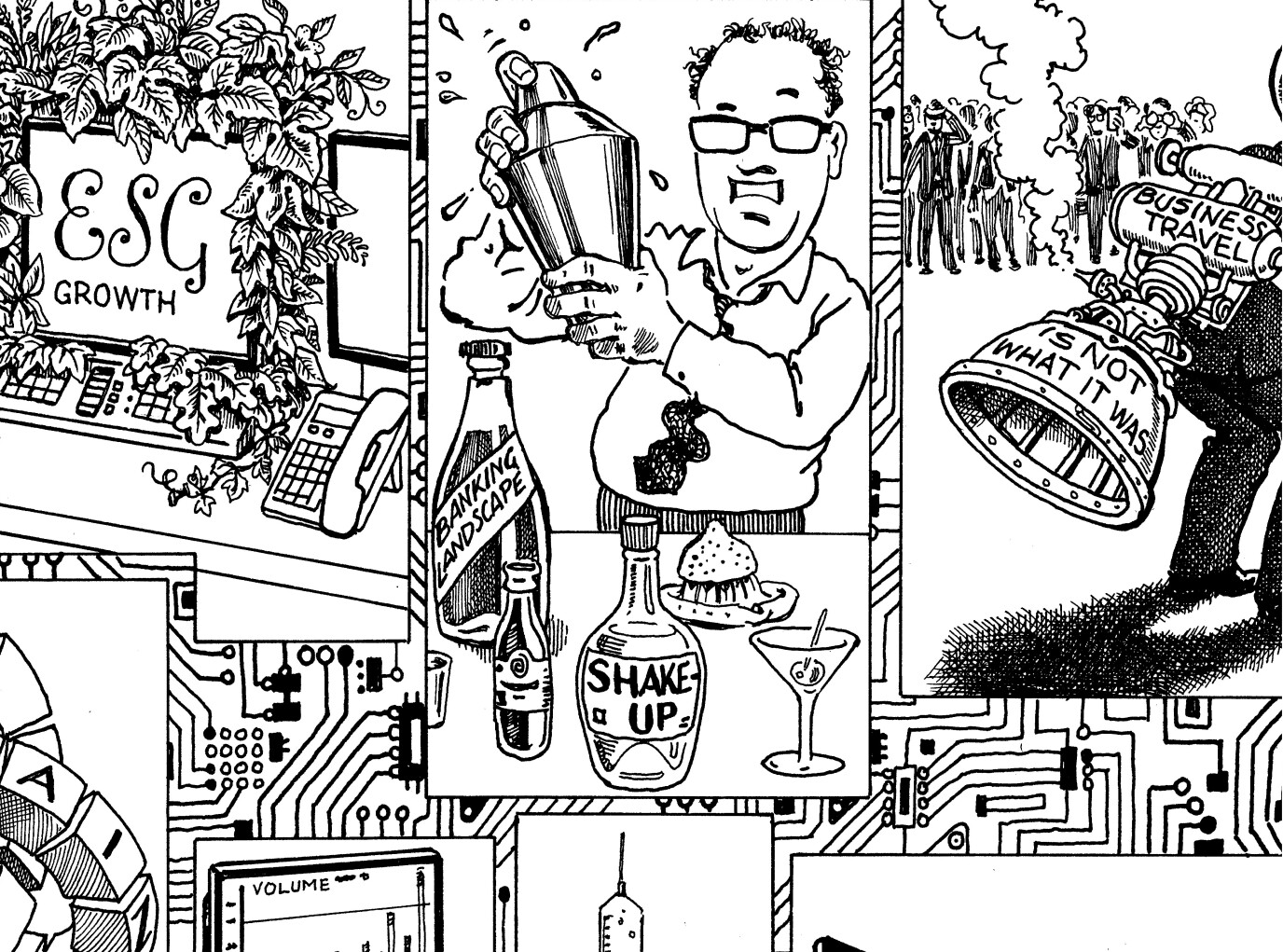

Overview — Covid and the capital markets: Turning crisis into opportunity

The global pandemic has forced those working in finance to re-evaluate how they do their jobs — whether it be working more from home and not travelling as much on aeroplanes or helping to foster more diverse and ESG-conscious workplaces. Some banks have also seen the crisis as an agent of change, to accelerate growth plans or implement new strategies. Eighteen months on from the beginning of the crisis, GlobalCapital looks at how successful they’ve been and whether they can make it stick.

Unlock this article.

The content you are trying to view is exclusive to our subscribers.

To unlock this article:

- ✔ 4,000 annual insights

- ✔ 700+ notes and long-form analyses

- ✔ 4 capital markets databases

- ✔ Daily newsletters across markets and asset classes

- ✔ 2 weekly podcasts