For the past decade, rapidly increasing trade links with China have powered growth in Latin America’s economies. The Asian nation’s demand for commodities, most notably minerals, food and energy, is underpinning the resurgence of South America.

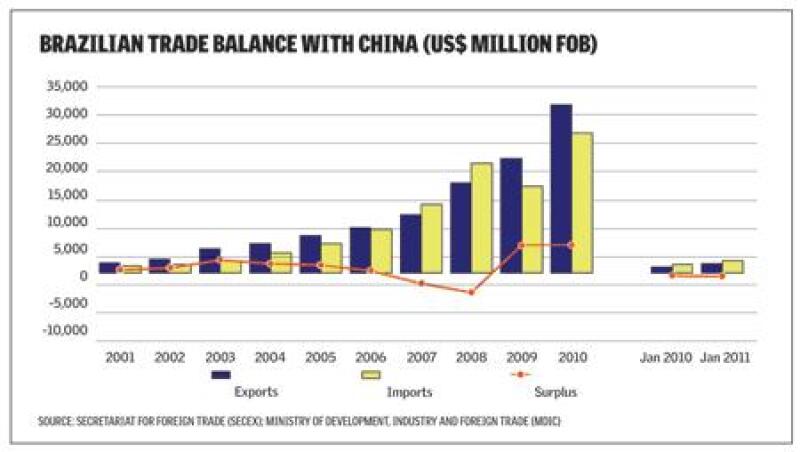

Brazil has been at the heart of this dynamic. Now the world’s sixth-largest economy, its exports to China have increased more than 40-fold, and its strong economic growth relies on continuing demand from Asia.

The rise in trade has also begun spurring financial and investment ties between China and Brazil over the past two or three years. And these links could create a much more interesting and varied bi-lateral relationship, extending beyond dollars in exchange for iron ore or soybeans.

“Until 2005, Chinese investments in Brazil did not add up to mu ch,” says Paulo Rogério Caffarelli, vice-president of wholesale, international business and private bank at Banco do Brasil, Brazil’s state-owned bank and Latin America’s largest by assets.

Indeed, from 1990-2009, confirmed Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) into Brazil added up to just US$255 million.

That all changed in 2010 when the figure jumped to US$9.5 billion.

Broadly speaking, the bulk of the investments centred around Chinese state-owned enterprises acquiring greenfield projects in Brazil to secure long-term access to strategic natural resources, such as oil, minerals or food. But mergers and acquisitions (M&A) are also on the rise and there has been a recent increase in manufacturing investments.

“Ninety-eight percent of [the rise in FDI] was in mining, agribusiness, steelmaking and infrastructure,” says Caffarelli. “But given the dynamism of the Brazilian consumer market, we can see an uptick in the announcements for investments in the manufacturing sector, especially automobile assembly, electronics and telecommunications.”

Regulations in Brazil can be time-consuming and difficult to navigate, but the barriers for the Chinese or any other foreigners are rarely greater than those faced by local businesses. The notable exception is in agriculture, where the explicit fear of Chinese land-grabs recently led the Brazilian government to pass a law limiting foreign acquisitions of land.

Yet while China’s investments into Brazil are rising, its lending to the country remains low.

“The offer of credit from Chinese commercial banks is still timid, and is usually linked to projects counting on the participation of state-owned entities like China Eximbank or the China Development Bank…but there [are good prospects] for it to increase,” says Ilan Goldfajn, chief economist at Itaú Unibanco, Brazil’s largest private bank.

One of the few big examples of this incipient practice was a US$10 billion loan from the Chinese Development Bank to Petrobras, the state-owned Brazilian energy company, in 2009. It sounds a decent amount, but to place it in context Petrobras pulled off a world-record US$70 billion share offering in 2010.

However an estimated US$1 trillion will be invested over the next decade to develop Brazil’s offshore, hard-to-reach, “pre-salt” oil deposits, which could turn the country into one of the world’s top five oil exporters. Some of the funding is likely to come from China.

There is even the potential for the two countries to forge a mutually beneficial relationship in infrastructure development, where offerings in Brazil are badly inadequate and for which China has ample capital and expertise.

That would be a constructive development in a story that is just beginning.

Relying on resources

Official numbers for China’s FDI into Brazil for 2011 are not in yet, but they are expected to be much higher than those for 2010 even given a secular trend that is rising over the next few years.

The incrase is expected because of a few big, chunky investments, two of which were overseen by UBS on the China side.

“They’re all related to natural resources, which is where a lot of the interest is going to be in Brazil,” says Stephen Gore, the Swiss bank’s Asia head of M&A and corporate finance. It’s a trend he expects to continue.

“The themes will stay the same in the short term,” says Gore. “And this is not a China-into-Brazil theme. The dominant theme for outbound Chinese investment is the long-term strategic objectives of the country and access to natural resources…I don’t think these deals are driven by short-term profit maximisation at all; they are driven by the much longer term, by China attempting to secure access to key supply lines.”

In November, Chinese oil refiner Sinopec announced it was taking a 30% stake in the Brazilian upstream oil assets of Galp Energia, to pay out US$4.8 billion. This was after Chinese conglomerate Sinochem announced an acquisition of a 40% stake in the Peregrino offshore oilfield from Norwegian energy company Statoil for US$3.07 billion.

Then in September 2011, a Chinese consortium comprising CITIC Group, Baosteel Group, Anshan Iron & Steel Group, Shougang and Taiyuan Iron & Steel acquired 15% of the shares of CBMM, a Brazilian family-controlled niobium miner for a cash consideration of US$1.95 billion (see box).

“It was interesting to see that all of these Brazil deals are relatively highly structured, and all very large in size,” Gore says. “It shows the sophistication of the Chinese. Compared to five years ago, there weren’t many like this…with the CBMM deal you had five state-owned enterprises signing up to some pretty complicated contracts, there is the 20% stake in the mine and then there are separate agreements between the five of them and the way they cooperate.”

Soya sensitivities

The Brazilian government welcomes investment from China, but it does not proactively encourage its fellow Bric nation.

Brasília tends to allow most foreigners in, but they have to navigate the country’s web of regulations and bureaucracy. Locals are used to the red tape, but it often delays projects much longer than anticipated.

Only in one specific area has China’s interest touched a political nerve: agriculture.

After iron ore, soya is Brazil’s principal export, and the principal destination is China. When the Chinese showed interest in buying up chunks of land, Brasília got nervous and put in place a law requiring approval of large foreign land purchases. Argentina and Uruguay followed.

“Agriculture is a sensitive issue everywhere,” says Miguel Pérez Ludeña, economic affairs officer at CECLAC, the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. “And Latin America, because of its land abundance and its history, actually has more liberal regulation for foreigners buying land than other regions…but there is a long-term concern with food scarcity, which is exactly what the Chinese care about, and [it has] a very large impact on the livelihood of a large percentage of the population.”

“The Chinese came quite suddenly,” Pérez says, “and there is the fear that there is a political agenda, since most Chinese transnational corporations are state-owned.”

The essentially anti-market government policy did not stir much controversy within Brazil.

“Our agricultural resources are very cheap compared to their potential, and we do need to create barriers to Chinese entry, or else we could end up owned by someone else, as much of Africa is,” says a high-ranking executive at one of Brazil’s largest private banks, who asked not to be named.

The specific interest of China in Brazil is that the latter is “incredibly rich in natural resources”, Gore says, “and they are at an early stage of development. Ownership is still available. In Australia it’s easier because you can just buy them on the stock market.”

As for bureaucratic holdup, “The Peregrino deal [in which Sinochem acquired a 40% stake in Brazil’s Peregrino oilfield from Norway’s Statoil for US$3.07 billion in 2010] took nine months to go through the Brazilian regulatory approval process.”

While agriculture investment remains a touchy subject, China’s interest in Brazil spans other sectors too.

In fact, there was an uptick in direct Chinese investment into Brazil’s manufacturing sector in 2011 – an unexpected rebuttal to those who lament that the Chinese-Brazilian relationship has been pushing the latter into a neo-colonial type commodity-exporting situation.

Most notable was Chinese car-maker Chery Automobile’s decision in June last year to spend US$400 million building a car factory in Brazil, and Sany Machinery’s US$200 million investment to build an engineering machinery base in February 2011.

Brazil’s boom has been powered not only by commodity exports but also by the rise of a new lower middle class, which has driven an increase in consumption. First-time sales for things like cars, refrigerators and washing machines make up the cornerstone of many an investment plan in Brazil. And because of Brazilian laws, there are strong incentives for cars to be assembled here.

Chinese brand Jac Motors has done well setting up entire operations in Brazil, despite high costs of production. And Chery appears to fancy its chances too, judging by its investment.

The infrastructure incentive

There are those who believe Brazilian manufacturing is doomed to die a slow, painful death as currency and cost pressures turn the country into a commodity and services economy.

Its manufactured products are proving uncompetitive compared with imports, a consequence of the appreciation of the Brazilian real, the huge interest-rate differential between the country and post-crisis rich countries, high taxes, high labour costs and infrastructure bottlenecks.

In response, Brazil’s government has declared a “currency war” and instated capital controls to keep the real’s value down and try to save the industry, which was almost completely stagnant in the second half of 2011.

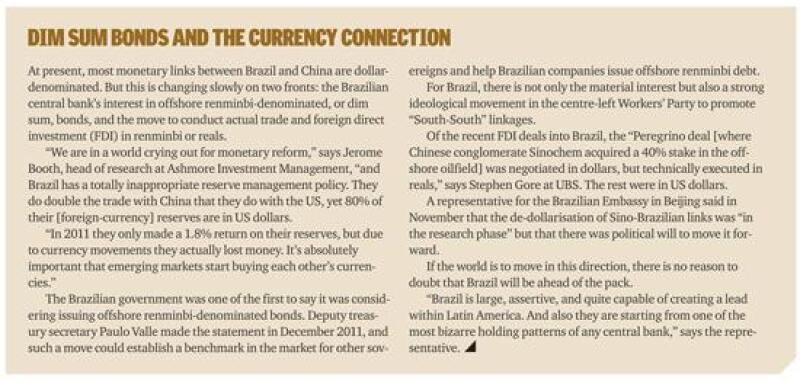

This approach may be shortsighted, says Jerome Booth, head of research at Ashmore Investment Management.

“Insofar as Brazil has an external sector, it is commodities not manufacturers,” he says. “The terms of trade are massively positive, and about to get more massively positive. And there will be Dutch Disease [the negative consequences arising from large increases in a country’s income]. If it was temporary, I might get it, but this is going to last for a long, long, time. When your comparative advantage changes, you accept it and you live with it.”

But while commodities may be Brazil’s main immediate advantage, the country could use its relationship with China to solve some structural weaknesses. In particular, it could look to China to help improve its infrastructure.

The South American nation needs up to US$1 trillion in investment, according to many analysts, to fix unpaved roads, overcrowded ports, woefully inadequate airports and a host of other problems.

“Brazil can attract that private international money to build infrastructure,” says Booth, “and the China connection is enormously important – they know how to built it, they can provide a huge amount of help, and they can capitalise the private sector.”

The nation could even leverage on China’s desire for more access to help it meet some of these demands, Booth says.

“You can say, ‘we need your help, and you can buy some land’,” he adds.

In his March report for the Vale Columbia Center on Sustainable International Investment, Pérez writes: “There are [Chinese] investments in other sectors [than oil, gas and mining], and these are likely to increase in the coming years, offering Latin American countries opportunities to improve infrastructure and develop certain manufacturers beyond today’s focus on the extractive industries.

“It should be remembered that Japanese and Korean outward FDI also started as primarily resource seeking, until rising local costs and technological progress pushed their companies into other types of investments.”

Goldfajn says that infrastructure and capital-intensive sectors in general have seen the biggest increases in Chinese interest since 2008.

“At some point,” says Pérez, “the speed and the level of the growth of infrastructure investment in China have to be decreased. Those companies must find a market somewhere. And they will be spurred to find it outside China. Latin America will not be the main target, but from our perspective here, there will be a great opportunity for companies that have great capacity, to access Chinese banks’ capital, and great expertise.”

Brazil’s resources might be its biggest draw for China today. But tomorrow it could be the roads, railways, ports and other infrastructure that the South American country so badly needs.