Vietnam is stumbling under a mountain of debt. And it could yet fall.

The country’s financial woes come courtesy of a huge influx of foreign direct investment (FDI) over the past decade, which fuelled an unwise spending spree by state-owned enterprises (SOEs) into unrelated businesses.

State-run utility PetroVietnam Oil & Gas (PVN), for example, stockpiled assets in construction, hotels and even a taxi company. Some SOEs had as many as 400 subsidiaries.

“It was like getting dad’s credit card and going to Las Vegas and saying ‘if I win I keep it and if I lose then dad has to pay the credit card bill,’” says Andrew Clarke, an analyst at VinaSecurities. “Something similar was going on here too. Why would a company have that many subsidiaries? They’re still in the discovery phase here. It’s really dawning on them how bad this could be.”

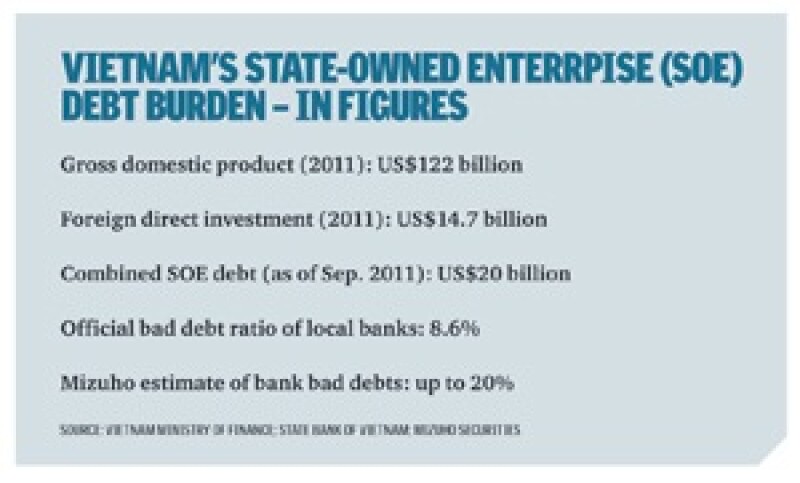

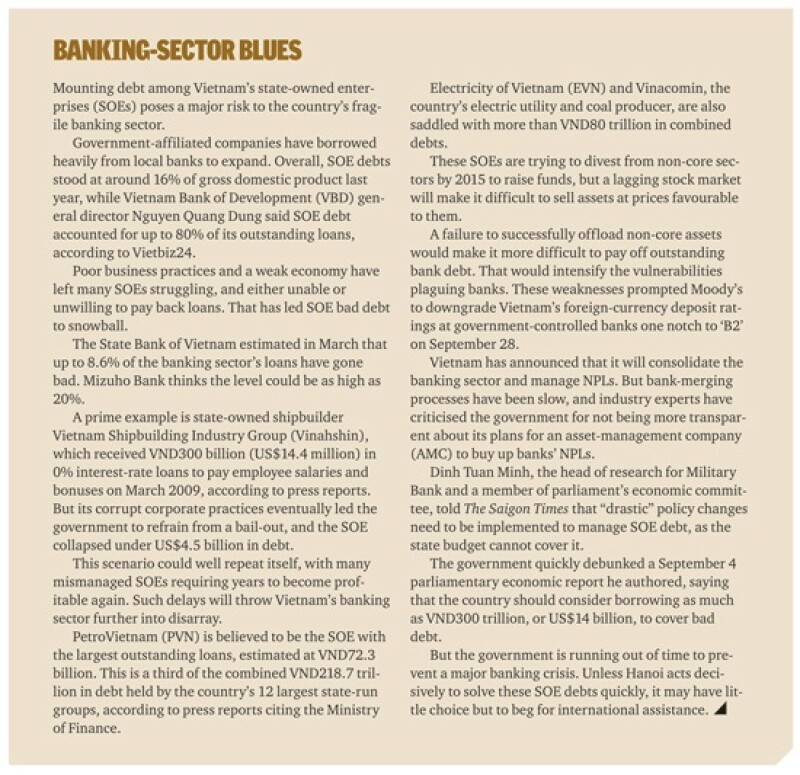

A July 17 finance ministry report showed that at the end of September 2011, Vietnam’s combined SOE debt stood at an estimated VND415 trillion (US$20 billion). That is 16% of the country’s US$122 billion gross domestic product (GDP) in 2011, mostly held by its troubled banks.

A lack of corporate governance and transparency helped SOEs buy these non-core assets through comfortable financial lines. As a result, many state enterprises, which account for about a third of the country’s output, have become too large and too weak. Several are effectively bankrupt.

The government is belatedly acting to solve these problems. On July 17 Prime Minister Ngyuen Tan Dung’s government began by stipulating in a grand plan that SOEs must liquidate positions in non-core businesses by 2015. The country has also kick-started discussions with the Asia Development Bank to restructure two SOEs first as models to help attract foreign capital.

Some high-profile arrests followed. On August 20 Nguyen Du Kien, who founded Vietnam’s largest lender Asia Commercial Joint Stock Bank, was arrested for “conducting business illegally”, according to the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV). The bank’s stock plunged to its daily limit of 7% the following day, prompting the SBV to inject liquidity into the banking system.

Next Duong Chi Dung, former chief of Vietnam National Shipping Lines, was arrested on September 5 on corruption allegations that resulted in US$4.5 billion in bad debt. About VND14.6 trillion was mobilised from the state budget to cover the losses, according to The Saigon Times.

Hanoi then announced on September 26 that oil and gas utility PVN will have to divest all of its non-core assets.

The key question now is whether these moves are too little, too late.

The increasingly parlous finances of Vietnam’s SOEs have weakened its banks. Mizuho Bank estimates that non-performing loans (NPLs) account for up to 20% of the outstanding total. On a scale of one to 10, where 10 is weakest, Standard & Poor’s ranks Vietnam’s banking system a nine. Despite its pledge to clean up the banking sector, the government has been widely criticised for providing little detail.

“We have clarified the issues to be resolved, including the NPLs, and the government has instructed the Ministry of Finance and the central bank to further accelerate the restructuring of these two sectors – finance and banking,” finance minister Vuong Dinh Hue told Asiamoney, seemingly skirting specifics.

To prevent the country’s banks from spinning into systemic crisis, Vietnam needs to finance about US$30 billion, according to an August 29 report by VinaSecurities and Macquarie.

Raising the money requires a rapid divestment of state assets into private hands, just as the government has envisaged. Such investments are also essential to help SOE projects, which are capital-intensive and cannot be funded domestically, or require advanced technology from outside.

But international investors are increasingly wary of Vietnam’s shoddy corporate governance and illegal operations, particularly after the recent arrests. To boost inflows, Hanoi needs to offer investors sizeable stakes in SOEs at attractive prices, despite heavy political resistance on both counts.

Vested interests

For years healthy foreign investment masked Vietnam’s grossly incompetent SOEs. In 2008, annual FDI levels hit a record US$72 billion.

The global financial crisis of 2008-2009 exposed the country’s problems. FDI collapsed and has not recovered, with inbound investment tumbling to US$14.7 billion in 2011.

Without this stream of cash, SOEs have been left in a debt hole. Debt defaults are a certainty; asset sales a must.

To this end, on June 27 the finance ministry announced plans to restructure 889 SOEs by 2015.

Of these, 367 enterprises are set to be equitised (a word the Communist Party uses to describe privatisation via a stock sale or strategic sales without having to mention the ‘p’ word). The other 532 will either be put up for assignment, sale, contracting, leasing or dissolution. Ninety-three SOEs have registered to equitise in 2012.

The government’s policy announcements and arrests show that Hanoi understands it must reform and tackle corruption. But it won’t be easy; many of the country’s elite do very well from the current system and are loath to see it changed.

For example, Vietnam’s SOEs are among its biggest companies, yet only six of them, including Lamthao Fertilizers & Chemicals JSC and PV Gas, were listed on the stock exchange as of August. The lack of listings appears largely a consequence of government officials wanting to protect vested interests.

“People are much more concerned about their jobs than about moving this process forward, even if they understand that they have to attract foreign investors. Nobody wants to take the responsibility,” says a senior official at an investment firm in Vietnam.

This unwillingness to let go of the reins has had another unpleasant side effect: unrealistic pricing expectations.

“Investors may need to pay a high cost to buy out existing management for their vested interest,” says Alex Kun, senior investment research analyst at Wells Fargo Private Bank in Hong Kong. “The management and leaders of SOEs often… circulate benefits of running the SOEs back to themselves through related channels. They prefer to keep SOEs under the government so that they can continue the opaque operations.”

The recalcitrant company apparatchiks have typically asked for an average price-earnings (PE) ratio of 30 times book for SOE assets, while investors believe nine or 10 times earnings is more reasonable, according to a Ho Chi Minh City-based foreign investor.

The government’s high valuation expectations look out of kilter with the performance of the Ho Chi Minh Stock Exchange. The benchmark index dropped into a bear market on August 27, after falling more than 20% from its May 8 high, and is 7% lower than a year ago, which means that SOEs would raise a lot less from initial public offerings than in 2011.

This index drop gives would-be investors ammunition to demand lower valuations. All too frequently, the result is a sizeable gap between where the government wants to sell and where investors are willing to buy.

Struggle to improve

“The financial market has not been friendly so far,” says Wells Fargo’s Kun. “Unfortunately the equity market has not really recovered since the global financial crisis. The incentive to equitise SOEs is missing unless the government can offer more discount. But it would mean that the selling price is too cheap.”

To solve this problem the government amended its Decree No. 59 on equitisation in April to let strategic investors buy shares at a price as low as the lowest successful bidding price. It also allowed strategic investors to purchase shares before private auction, but they have to hold them for at least five years, up from three years before.

“The regulations are changed, they haven’t completely fixed the issue but there has been some progress made,” says Jerome Buzenet, a partner at law firm DFDL. “But it’s a very difficult political decision to be made by the government to sell something out to foreigners which is lower than the IPO price.”

SOEs such as Vietnam Steel Corp., the country’s largest oil importer and distributor Petrolimex, Mekong Housing Development Bank and Bank for Investment and Development of Vietnam saw their average winning prices rise only around 1% from when they IPOed in 2011. These companies are not yet listed and currently trade on the over-the-counter (OTC) market, which lacks price transparency.

Another sticking point is the government’s reluctance to surrender control of its SOEs. Foreign strategic companies like to buy major stakes in companies, but Hanoi prefers selling stakes that are too small to give foreign stakeholders a meaningful say.

For example, PV Gas was listed in May, but the government only put up 5% for sale. That deterred foreign investors, who only bought 4.5% of the available shares. The government’s stronghold on cashflows has also made it difficult for investors to seek larger dividends.

“They have to sell large-enough portions so that the corporation now is not a government corporation and that shareholders will start having certain rights and corporate governance improves,” says Marc Djandji, senior vice-president at Indochina Capital. “But if the government is holding 95% of the company, nothing’s really changed.”

The government’s unwillingness to loosen its grip on SOEs is a consequence of the private interests held by enterprise managers. Public officials who know this must change are puzzled as to how to progress.

“The process of reform for SOEs, together with public investment and the financial sector, these three areas we emphasise are … very complicated, because that’s politically sensitive and socially sensitive,” says Vo Tri Thanh, director of the Central Institute for Economic Management (CIEM), which is directly related to the Ministry of Planning and Invesment.

Without a way to untangle the corrupted parts of SOES by transferring controlling stakes in newly listed companies outside of government, foreign companies have little incentive to purchase assets in Vietnam.

“We’re not really focusing actively or waiting for those assets to be equitised because history has shown that they are sold at a too-dear price or they haven’t sold enough of it to make it really significant,” says Djandji.

Only 1.2% of shares offered by Hanoi Beer Company (Habeco) in March 2008 were purchased by foreigners amid concern that the initial price of VND50,000 was too high. The lack of reception pushed the average winning price to merely VND50,015.

How to make progress

As things stand, Hanoi has begun saying the right things but it isn’t doing enough to entice investors.

The government’s first step to improve corporate governance and transparency should be to speed up the equitisation process. It needs to explain to SOE managers and workers the benefits of listing and inviting foreign investors into the board room, with advanced management expertise and technology potentially boosting competitiveness and hence cashflows.

To facilitate this, obstructive senior officials should be removed and corrupt dealings stamped out. One way would be to get the state’s official auditor to examine the dealings of senior management and set the legal ground rules to strengthen transparency.

Then the SOEs should be prepared for a public listing, poor stock valuations or not. That will force disclosure requirements on to the public entity, bringing to light financial problems.

The government must also further loosen equitisation rules to make them less limiting for strategic investors. This can be done by eliminating restrictions on the number of years investors have to wait to transfer their holdings from five years. Decree No. 59 also caps the number of strategic investors to three. Raising that number may give investors the comfort of dispersing risk.

Foreign companies should be allowed to buy larger stakes in SOEs by raising the 49% cap on foreign ownership. Increasing foreign influence in board decisions will also help Vietnam import management skills, guiding local companies via international models.

The government must also offer fair valuations to entice investors.

“The value of the enterprise should be very much based on the market,” says CIEM’s Vo. “The key is how we can not just attract the capital but more importantly how we can get new technology, new skills of management for the equitised SOE.”

With foreign inflows tapering off, the current status of debt-laden SOEs and a struggling banking sector is no longer sustainable.

Hanoi needs to combine a willingness to fight corruption with a willingness to grant foreign investors increased rights and flexibility in the SOE sector. And it must do it fast, before its bad-debt burden becomes too heavy to handle.