Beijing’s newest financial experiment had economists and trade experts cautiously optimistic that it could prove the first step in a renewed round of liberalisation that ultimately leads to the freeing up of China’s capital controls, inward investment and financial markets.

China opened the doors to its latest financial experiment on September 29, when it launched the China (Shanghai) pilot free trade zone. Institutions that set up operations in the zone will be able to participate in activities denied the rest of China.

The specifics remain rather vague, but experts believe that China’s authorities intend to use the FTZ to introduce several experimental reforms. These include offering a more streamlined regulatory environment that’s more in line with international trade and investment norms, allowing local and international companies operating in the zone fare more freedom to access offshore and onshore financial markets, respectively, and offering foreign companies lower requirements to participation in six key sectors unless prohibited by Beijing.

The FTZ is also set to introduce a ‘negative list’ in which certain activities are banned, but everything else is not.

Economists anticipate that the zone points to a desire among China’s policy heads to experiment with further capital liberalisation and eventually full interest rate and currency convertibility.

“This move indicates that China’s financial sector reforms and capital account convertibility will accelerate, and Chinese policymakers attach great importance to investors' concerns and are looking forward to a favorable "micro-environment" for international investment and trade,” said Li-Gang Liu, chief economist for greater China at ANZ in a note on September 30.

New possibilities

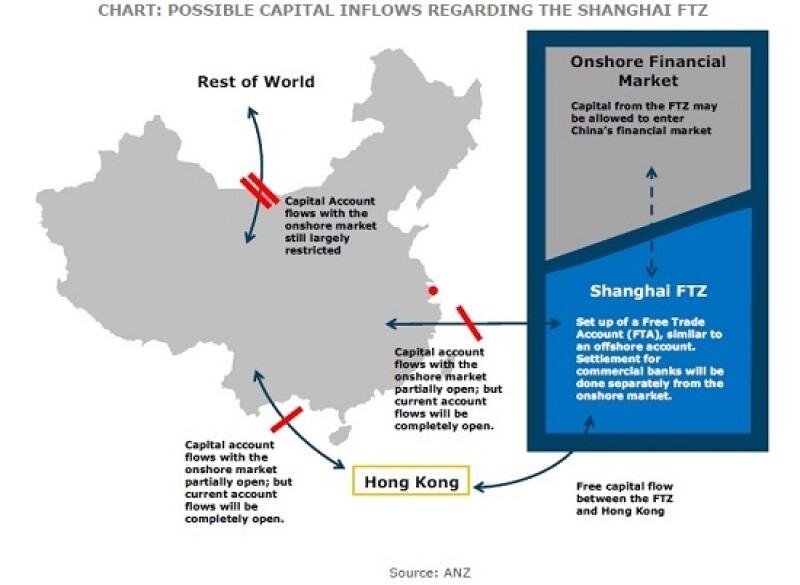

Companies, financial institutions and individuals that base themselves in the FTZ will be able to set up a free trade account, similar to an offshore account. This will let them freely move current account flows on and offshore, while capital account flows will become partially convertible.

Using these accounts, FTZ-based organisations can conduct several activities. For a start they will be encouraged to take part in onshore and offshore renminbi markets, and invest into onshore and offshore financial markets too. This will ease capital restrictions, allowing foreign money into China’s financial markets and vice-versa. Overall, the STZ offers many more options to move money into and out of China than other existing options.

This has a number of product possibilities for banks in particular and means that many are likely to eventually set up branches or joint-venture operations in the FTZ. It also means that foreign companies setting up in the zone can issue onshore renminbi bonds, something of a rarity to date.

The new zone has implications for commodities too, with foreign participants set to eventually be allowed to participate in onshore commodity futures trading.

The zone also offers opportunities for foreign companies. Barriers to entry have been lifted across a set of service sectors including banking, shipping, commercial, professional, cultural and social services, according to HSBC.

The bank notes that each sector has separate advantages when operating in the STZ. Qualified foreign financial institutions can set up foreign banks, and qualified domestic private institutions can establish joint-ventures with foreign lenders. Chinese banks operating in the STZ can also offer offshore business, facilitating investments outside the country.

In the shipping sector, the foreign equity limit for Sino-foreign companies operating international routes has been reduced, while in commercial services foreign investors can enter value-added telecom services and international companies make and sell game machines. Foreign companies will be able to offer a raft of professional services such as legal advice, human resources, travel agency, investment management and engineering design; entertainment companies can set up shop in the FTZ; and education JVs with international partners and wholly foreign-owned medical institutions are also permitted.

This liberalisation is expected to offer many new opportunities to foreign companies participating in these sectors, potentially increasing investment into China via the FTZ. Its rules are also designed to encourage international companies to set up their regional headquarters inside the zone.

“The FTZ has to do with the progressive opening up of China’s financial sector as well as most of China’s economy,” said Neil Ge, chief executive officer of DBS Bank (China) to journalists on September 30.”

He added that Beijing appeared to view the FTZ as far more progressive in its goals than other special economic zones such as Qianhai, Shenzhen, which was established as a place for financial reform in cooperation with Hong Kong but has proven limited in its impact. “The Shanghai FTZ is a progressive evolution to China’s economy,” Ge said.

The FTZ also looks like an attempt by China to enter the global free trade discussions currently going on too, most particularly the US-led Trans Pacific Trade Partnership.

As HSBC notes, “the era of 20-30% exports growth is gone. To make services trade a larger driver to growth, China needs to sharpen its competitiveness in services trade through deregulation and opening-up to foreign investors.”

Staying realistic

While the FTZ offers a tantalising glimpse into a reformist China, it’s best not to get carried away quite yet. The media was quick to note that neither president Xi Jinping nor prime minister Li Keqiang attended the opening of the new trade zone.

Their absence either suggests that the zone is considered something of a gamble with the potential to fail. The government is likely to prove cautious over the development of the zone and will quickly change the rules if its sees capital flows developing in a manner that displeases them. Beijing is unlikely to want to see its FTZ become a means to circumvent all of the capital controls it so assiduously maintains over the rest of the country.

For this reason, combined with the general lack of specifics about what is and isn’t allowed, has led to a cautious response from international banks. As of yet only Citi and DBS have applied for and received sub-branch licences in the FTZ.

As Liu says in his note, the marked interest rate differential between China and offshore markets could encourage many onshore companies to try to establish an FTZ presence to get access to cheaper offshore funding, while international investors seek out the higher returns offered by onshore debt instruments. China’s authorities will undoubtedly keep a close eye on the level of capital entering and exiting the country via this new financial hotbed.

The establishment of the FTZ also raises questions for Hong Kong, which until now has been China’s favoured testing ground for financial reforms. Some of the city’s financial services and port capabilities risk diminishing if international companies and investors find that it’s simpler and cheaper to send their money and goods into China via the Shanghai trade zone.

Then again, the pilot nature of this FTZ is likely to leave international companies cautious, and unwilling to abandon the transparency and rule of law offered by Hong Kong any time soon. The direct competition offered by the FTZ could even spur Hong Kong lawmakers to consider reforms of their own.

China’s plans for its FTZ make a lot of sense, and offer a glimpse of the country’s willingness to slowly open itself to international markets. But it will be a slow and steady process. Patience will most definitely be required.