The ending of Sri Lanka's civil war in 2009 kicked off an economic transformation for the country. GDP growth that came in at just 3.5% that year rose to an average of 7.5% over the five years that followed, according to Moody's.

The change in the fortunes of the B1/BB-/B+ rated nation not only represents a big improvement from the past, but also stacks up impressively against other countries. Growth rates of other double B and single B rated countries over the same five year period averaged only 3.9% and 4.4%, respectively.

“Sri Lanka has developed by leaps and bounds since the end of the civil war, be it in the area of infrastructure development, tourism, or GDP growth,” says Aaron Russell-Davison, head of debt capital markets at Standard Chartered.

The country has always benefited from strong remittance inflows, which contributed roughly 30% ($7bn) of its total external receipts last year. But now that it has been able to enjoy a prolonged period of stability, Sri Lanka is able to better channel the money into the economy. Private consumption constitutes 65% of the country’s GDP, with a big part of that supported by remittances.

Anushka Shah, a sovereign analyst at Moody's, says the country’s growth has been robust but that the key to longer term economic development lies in another area — infrastructure investment, which has ticked up over the last five years, partly as a result of post-war reconstruction efforts. It now stands at around 30% of GDP.

So far this effort has been led by the public sector, with the government embarking on large-scale investments in power, roads, ports and aviation. Examples include the Colombo South Harbor project, the Hambantota Port development project, the Norochcholai coal power plant and the Southern Expressway linking the southern city of Matara to Colombo.

Shah notes that projects in the maritime sector in particular can add to Sri Lanka’s competitive advantages as a port destination, given its proximity to various international shipping routes and its competitive tariff structure.

The direct benefits of these projects have been well documented, but a bigger boost comes from the knock-on effect that such projects have on the broader economy, says one Singapore based economist. An army of workers is needed for the projects themselves, but plenty more to service those workers — and the completed projects. Unemployment stood at 5.9% in 2009; this year it might fall to 4%.

“You obviously need a lot of construction workers, but these projects will also require extra input from the utility, logistics, commodities and resources sectors to name a few, and also the local communities,” says the economist.

Reliance on foreign financing

The problem is how to fund it all. A disconnect between domestic savings and the country's investment needs raises concerns about the government's ability to provide the required support, says the economist. Domestic savings have risen from 19.3% of GDP in 2010 to 21.1% in 2014. But that still pales in comparison to the country’s gross investments, which also rose from 27.6% to 29.7% of GDP over the same period of time.

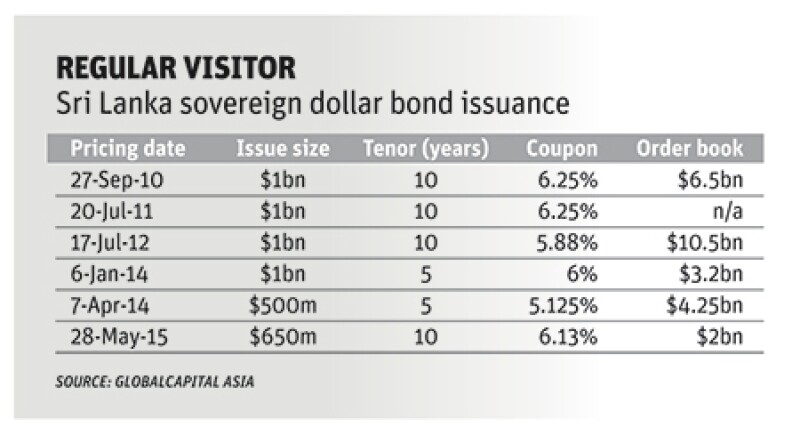

Unable to fully fund itself domestically, therefore, the sovereign has been plugging the gap by relying on the international market. The dollar bond market, in particular, has been the weapon of choice thanks to the currency’s consistently low yields. The sovereign has raised a combined $5.15bn from six internationally marketed transactions since 2010, according to Dealogic.

“Sri Lanka has been a keen student of the international capital markets for a long time, but the biggest catalyst for me was really the end of the civil war," says StanChart's Russell-Davison. "Above all else, bond investors require a degree of stability to be comfortable and deploy funds."

Sri Lanka ended a 27 year civil war in 2009 when government forces reclaimed the north of the country from the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam, a separatist group. The government had regained control of the east of the island three years earlier.

The country’s improved stability and impressive growth story meant international investors have been more than happy to put their money into its bonds since the ending of the civil war. Issuance has also neatly coincided with a reduction in the number of international bonds from the likes of South Korea and the Philippines, notes Russell-Davison.

Political instability

Sri Lanka's honeymoon period with international bond investors could soon face a stiff test, however, with the US set to raise interest rates as soon as September. That would have an impact on the cost and availability of international financing, according to Sagarika Chandra, an analyst at Fitch, although other factors are also starting to peel away Sri Lanka’s attractiveness.

Top of the list is the uncertain political climate that the country is once again facing this year. Sri Lanka experienced a change in leadership in January when Maithripala Sirisena surprisingly defeated incumbent president Mahinda Rajapaksa in January, despite the latter still commanding a lot of support in the country. The two sides have been locked in a political struggle since and the economy has shown signs of suffering. GDP growth slowed to 6.4% in the first quarter of 2015, down from 7.6% in Q1 2014.

The sovereign's most recent bond issue, a $650m 6.125% due 2025 that was priced in May 2015, had been delayed from the first quarter as a result of the jitters. That deal was more than three times subscribed, but previous deals had been much more popular. A $500m 5.125% five year in April 2014 attracted more than $4.25bn of orders.

And it is not just bonds that have been affected by political instability. Equity trading volumes on the Colombo Stock Exchange have fallen drastically this year. Average daily trading in the first three months of 2015 was Rp1.18bn, down 30.7% from the same period in 2014.

More disruption came in the form of parliamentary elections on August 17.

“The country’s growth story is actually pretty good although two elections in seven months appears to have weighed on business confidence, investment plans, and overall growth prospect,” says Kyran Curry, a S&P credit analyst in Singapore. “Growth is expected to weaken and I think the 7.5% target set out by the government by 2017 appears slightly ambitious.”

Debt-laden

Curry now expects the Sri Lankan economy to continue to slow down, with GDP growth to come in at around 6%.

“It’s hard to make any conclusions since we’re in an election process, which poses risks to Sri Lanka's institutional and governance effectiveness,” says Curry. “The best scenario we can hope for out of this is that a government with a clear mandate for policy continuity will prevail following the parliamentary election.”

As of August 19, that seemed likely to happen, with final results of the elections revealing that the United National Party (UNP) had won 106 out of 225 seats. Former president Rajapaksa’s United People’s Freedom Alliance took 95 seats. While the UNP is still seven seats short of a majority government, observers say it has more than enough allies in the parliament to make up the shortfall.

Even if that were to happen, Curry is worried that the UNP might not address some of the country’s most urgent needs. None of the political parties that competed in the August election mentioned ways to improve the government’s revenue performance, he notes. This is especially important for a country such as Sri Lanka, which enjoys the unwanted tag of having one of the highest debt to GDP ratio among its peers.

That ratio stood at 71.8% in 2014, even higher than the 70.8% recorded the year before. In neighbouring Vietnam, it is just 45%.

More than 40% of Sri Lankan government debt is owed in foreign currency, which exposes the government to a higher repayment burden in the event of currency depreciation. A reliance on foreign currency debt also exposes it to international market volatility during periods when foreign financing is scarce. A US interest rate hike is likely to put pressure on both fronts.

The situation looks even more daunting once government-guaranteed debt is taken into account, which poses additional contingent liabilities on the government’s balance sheet. The January 2015 budget statement estimated the amount of government-guaranteed debt to be equivalent of 14.5% of GDP.

“It’s hard to say whether any of the political parties have the commitment to push through the necessary reforms to improve the country’s economic and fiscal performance or they are simply more interested in shorter-term populist policies,” says Curry.

“When it comes to situations like this it’s probably more important to keep track of what they do rather than what they say,” he adds.

Not all bad

Despite the country’s internal woes, one Singapore based fund manager is convinced the country will bounce back once the political situation subsides.

He agrees the country’s debt situation is concerning, but points out that unlike many of its similarly rated peers, Sri Lanka has never yet defaulted. The central bank has on more than occasion made it clear that it intends to do its utmost to preserve that unblemished record.

In addition, even though he concedes that more could be done to rein in the country’s debt ratios, he notes that Sri Lanka has been making progress in other areas, such as reducing its fiscal deficit as well as inflation.

Sri Lanka has long been suffering from a current account deficit, although that has been tightening over the past few years. In 2011 the deficit stood at 7.2% of GDP, but fell to just 2.6% in 2014. It is expected to break through 2% by the end of this year.

“The accumulation of debt is an inevitable part of economic growth. You can’t run away from that,” says the fund manager. “The key for us investors is to see if a country is reckless with its expansion plans or is doing things in a controlled manner.”

What is more impressive in his eyes is the progress the country has been able to make when it comes to controlling inflation. Having peaked at 18.7% in 2007, it had fallen to just 2.4% by the end of 2014.

Lower commodity prices helped, but a large part of the reduction was attributable to prudent monetary policies and structural changes to address supply side constraints.

The fund manager is particularly happy with the work done by the central bank over the past few years. He sees April's 50bp reduction in policy rates as a reflection of the bank's increasing savviness and flexibility.

“Reining in inflation has given it more room to continue easing to spur economic growth and support economic activity," he says. "It’s all one big co-ordinated effort."

This co-ordination is one of the things that he likes most about Sri Lanka. Many emerging market government bodies typically do not work well with one another. The worst, he says, do not communicate at all.

“At the end of the day, this is a country that’s just came out of 27 years of civil war, so political stability is definitely a factor in our investment decisions,” he says. “What is important is what comes out of the instability and whether there will be any continuity.”