Hong Kong’s offshore renminbi bond market has been around for nearly two years, during most of which it was a sleepy place. All of that changed this year, with a rash of new borrowers clambering over each other to issue debt into the former British colony.

And the reason for this sudden interest? Cheap money.

In an effort to contain a stubbornly high inflation rate, which hit 5.3% in April, the People’s Bank of China has raised interest rates four times and hiked the required reserve ratio (RRR) of local banks seven times since October 2010.

As a result the country’s one-year lending interest rate has surged from 5.31% to 6.31% over the same time period, while RRRs have rocketed from 17% to 20.5% in six months. This has left bank lending less available and more expensive, which in turn has driven Chinese corporates to seek out money from other means.

With its relatively lower interest rates, the offshore renminbi bond market has been the perfect target. Onshore debt financing generally costs 200-300 basis points more than equivalent offshore renminbi debt, according to a credit analyst.

“Onshore credit conditions are tightening at a time when Chinese corporates have real funding requirements. This helps explain the deluge in issuance from China this year,” says Viktor Hjort, head of fixed income research for Asia at Morgan Stanley.

The cost arbitrage has caused a deluge of Chinese companies seeking to raise funds, making dim sum bonds the fastest-growing credit instrument in the world.

Deutsche Bank expects the gross issuance of offshore renminbi bonds to reach Rmb150 billion (US$23.1 billion) and total bonds outstanding to double to more than Rmb200 billion by the end of this year.

“It’s much cheaper to borrow renminbi in Hong Kong than in China, so there’s a strong temptation for Chinese firms to do so and move the proceeds back to the mainland. I bet seven out of 10 firms would do that,” says a debt capital market (DCM) banker in Hong Kong.

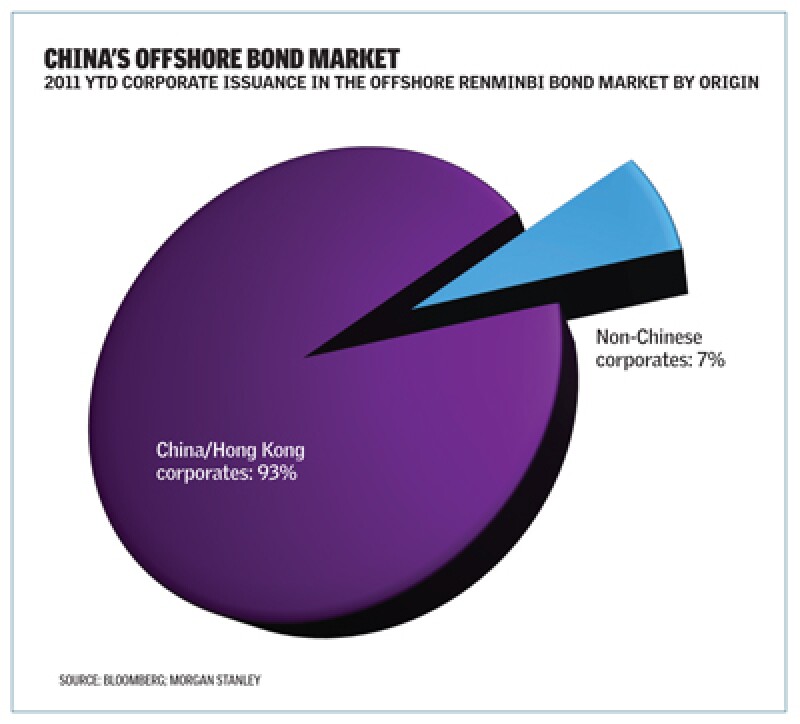

Local Chinese corporates have raised roughly Rmb24.86 billion in offshore renminbi bonds, accounting for about 74% of the total Rmb33.5 billion of debt issued in the first four months of 2011, data from Dealogic shows.

Strip out sovereign, quasi-sovereign issuers and supranational corporations, and 93% of the corporate dim sum bond issuers this year were domestic Chinese companies.

So far this glut of issuance has been eagerly snapped up by the city’s renminbi deposit base, which has also accelerated rapidly thanks to expectations that the currency will continue appreciating.

Hong Kong renminbi deposits grew to Rmb451.4 billion in March, a jump of more than six-fold from a year ago, according to statistics from Hong Kong Monetary Authority. Deutsche Bank expects Hong Kong’s renminbi deposits to reach Rmb2 trillion in the coming 24 months.

But this rising pool of money deserves exposure to a much broader diversity of assets and financial instruments than merely the bonds of high yield mainland borrowers. Such a narrow focus, both in terms of nationality and of risk, looks unhealthy for a newly available currency that by its very nature is meant to be international.

Beijing must encourage a far broader array of borrowers and financial instruments if it wants the offshore renminbi to continue cantering along unimpeded.

Meagre overseas appetite

Given the low absolute yields in the dim sum market, the low level of participation from overseas borrowers so far is somewhat surprising.

However their lack of interest points to the market’s limitations. The principle one is the relative cost of funds. For all the relatively low yield of dim sum debt, many international corporates still find it more cost-effective to raise funds in US dollars and swap the proceeds into renminbi or buy it spot.

“It’s not necessarily cheap if a company raises renminbi and plans to swap back to US dollars. The cost advantage to issuing CNH [offshore renminbi bonds] over US dollar so far is limited and in fact negative,” Hjort tells Asiamoney.

Only those multinational companies with a natural demand for renminbi funds find renminbi bond issues more appealing.

There are a number of these. Many foreign companies have a sizeable presence in mainland China, such as fast food restaurants operator McDonald’s. For them the ability to raise renminbi funding offshore and remit it into China would make a lot of sense, since they cannot fund their operations through the highly restrictive domestic bond markets and they do not tend to be the topmost clients of local banks, especially now the financing capabilities of these banks are being squeezed.

Unfortunately the process of remitting renminbi into the mainland remains very opaque. That uncertainty has led international companies venturing into the renminbi market to limit their funding ambitions.

Foreign firms that have issued dim sum debt have been modest in their ambitions, issuing relatively small deals with maturities of three years or less.

The A1-rated Mitsubishi UFJ Lease & Finance, for example, raised Rmb200 million (US$30.5 million) in a three-year offshore renminbi bond issue on March 31, while three days beforehand British-Dutch consumer products manufacturer Unilever raised Rmb300 million in a three-year dim sum transaction.

Such small, short-term deals do not do a great deal to attract long-term investors such as pension and insurance funds into the market; neither do they greatly help meet the funding needs of the Chinese operations of international companies.

Even those international companies that have already conducted issues seem to have done so to demonstrate to Beijing that they are an early adopter of the evolving dim sum bond market. But their unwillingness to conduct bigger deals with longer maturities speaks volumes about their lack of faith that such transactions would succeed.

What should be done

Unless this is rectified Beijing risks stymieing one of the key resources it needs to further internationalise the renminbi – providing worthwhile offshore instruments in which international investors can invest the currency.

An easy way to rectify this would be for the country’s regulators to encourage international borrowers to raise more funds in the currency. And a simple way of doing that would be to offer a clear idea about the process of gaining approval to move offshore renminbi proceeds into China.

Letting foreign companies raise renminbi and remit it would also reduce the foreign currency inflows that the People’s Bank of China has to sterilise. As things stand the central bank has built up a colossal US$3 trillion in reserves by having to do so, and the sum is now so large that it can effectively do very little with it.

Additionally, the regulators should try to encourage foreign borrowers to issue longer-dated tenors, rather than just focus on securing short-term financing.

There are some hopes that greater confidence in renminbi debt is building among international companies. On May 5 Global Logistic Properties (GLP), a logistics unit of Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund GIC, pushed the market further and became the first company to sell seven-year dim sum bonds, via a Rmb3 billion dual-tranche debut. The deal was split between a Rmb2.65 billion 3.375% five-year tranche, and a Rmb350 million 4% seven-year portion.

Despite its small size the seven-year debt will hopefully incentivise other companies to consider longer-term bonds.

Hong Kong blue-chip utility firm Towngas tells Asiamoney in an interview (see page 13) that it also intends to issue a second dim sum bond carrying a maturity of seven to 10 years, as the firm aims to secure a longer term financing and offer duration diversity in the evolving dim sum market.

Additionally, dim sum bond investors so far tend to buy the instruments and hold them. Adding duration diversity would attract more duration buyers such as insurance companies and pension funds, helping to foster the development of a more robust secondary market.

Investment products

Hong Kong needs to offer more deal diversity because that there is every sign that its renminbi deposits will continue to soar, meaning more money seeking a home with decent returns.

“We need to deepen Hong Kong’s role as a key offshore centre for the trading of renminbi. We need to make sure all parts of the engine are firing at the same time,” Gordon French, head of global markets, Asia-Pacific at HSBC tells Asiamoney. “That does include bond issuance, the broadening of deposit base, and a wider range of investment products.”

A much-heralded sign of such expansion was the first offshore renminbi initial public offering (IPO), which was conducted by Hui Xian, a real estate investment trust spun out of Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka-shing’s Cheung Kong Holdings on April 29.

Unfortunately it proved to be a disappointment. The company’s shares fell 9.4% on their market debut to close at Rmb4.75 a share.

In spite of its dismal first day of trading, the listing has been hailed as an important milestone for China to internationalise its currency and for Hong Kong to be the key offshore renminbi hub.

Others are more cynical, noting that international companies would far rather gain approvals to list directly in Shanghai or list in Hong Kong dollars in Hong Kong. The appreciation of the renminbi is less a factor for equities than it is for debt, they note, because the value of equities varies, whereas the principal value of bonds stays the same, meaning that as long as the underlying currency appreciates they will be worth more come maturation.

Despite this there is the scope for more renminbi-denominated instruments to join the fray. French believes a renminbi-denominated exchange tracker fund (ETF) could be the next possible candidate to join the growing market.

“ETFs are along those lines. For liquidity reasons, flexibility and costs, ETFs look set to be the few frontrunners to join a whole range of renminbi-denominated products,” he says.

Longer-dated and larger bonds, a broader array of international borrowers, new equity issues and ETFs; all these instruments will be needed to help ensure that the renminbi continues to smoothly internationalise – at least until that distant day when China makes its currency fully flexible.