China’s economy is finally undergoing growing pains.

After more than a decade of unparalleled economic growth, the country is beginning to post some troubling economic data. Inflation is higher than Beijing would like it, while China’s annual export growth grew 13.4% in December – the slowest level since November 2009.

More of a concern was imports growth, which during the same period sank to a 26-month low of just 11.8% year-on-year, much to everyone’s surprise. Economists agree domestic demand is slowing. And fast.

The good news is that Beijing has enough space to respond to these issues. On the monetary policy front the central bank has some room to cut interest rates to protect domestic consumption. The interest rate swap markets were pricing in 76 basis points (bp) of cuts in the next three months as of January 10.

It’s also likely that the People’s Bank of China will continue to cut banks’ reserve requirements in order to boost corporate credit lines.

The central bank cut the required reserve ratio (RRR) for the first time in three years in November, signaling an important change in policy position. Banks including Nomura expect RRR to be cut by 200bp by the end of 2012.

But while giving the banks more liquidity will spur more lending, it is not the cure to all ills.

As things stand, a handful of top-tier Chinese banks are conducting a substantial amount of the corporate lending in the country. That creates sizeable counterparty risk, and it means that companies risk tapping out their credit lines with these lenders.

What’s more sensible for China’s economy as it continues to grow is that banks encourage and participate in other forms of financing that better distributes credit risk.

The natural successors of this financing risk should be the equity and bond markets. While China’s banks can and do take some credit risk in the form of underwriting, a wider pool of investors is involved to take to major risk.

And there lies the rub. Over the past several years Beijing has made a lot of effort to open up the capital markets. But the result of these efforts is still a fairly limited market, particularly on the credit side, which has grown at nowhere near the pace of its economy. China’s capital markets are not up to the financing requirements that the country needs.

It’s an issue that the country’s new leaders need to rectify. There are signs that the country’s regulators are grasping some of these concerns. But a lot more still needs to be done.

Past issues

Beijing recognises the need to expand its financing options, but it is hobbled by a combination of the desire to retain control of its economy and previous painful experiences.

In the past, hurried attempts to open up particular areas have come a cropper, leading to credibility issues that are hard to erase.

A case in point is China’s previous attempt to open up a government bond futures market in 1992. The market was closed down within two years amid systemic speculation, price manipulation and inadequate regulation. Beijing set it up for the right reasons – offering domestic bond investors a suitable hedging tool – but a complete lack of appropriate controls led to its downfall.

Ostensibly there are signs that Beijing is willing to deepen its financial markets through new reforms.

In the early weeks of 2012, the China Securities Regulatory Commission’s (CSRC) new chairman Guo Shuqing made very pleasing noises about plans to introduce short selling on the stock markets and to once again introduce bond futures – hopefully having learned from its first disastrous attempt.

In principle these are both positive moves. But the devil is in the detail, and the CSRC has not as yet offered much public detail on these plans, especially for bond futures.

Even assuming these markets are surrounded by appropriate regulations there is no guarantee that they will be used in sufficient numbers to be of any economic benefit.

The National Association of Financial Market Institutional Investors (Nafmii) has made great moves to provide many hedging tools as an aid to bond issuance and to protect against foreign exchange (FX) risk.

Examples include introducing China’s equivalent to credit default swaps to the marketplace and, in the case of the State Administration of Foreign Exchange (SAFE), allowing corporates to hedge their renminbi-related currency risk using options. On both occasions the regulator chose not to allow investors to do more than hedge their exposure.

Yet these new products have been rarely used, especially in the case of credit risk mitigation, where Nafmii figures show usage is still limited. The trouble is that these tools are only really useful if certain fundamental regulation revisions – such as greater access for investors to China’s bond market – are conducted to open up the primary markets.

Man on a mission

Even so, the installment of Guo at the top spot in the CSRC is a positive move.

Many in the industry expected that the former chairman of China Construction Bank would make a quick impression in his new role heading the CSRC, and he certainly has. First and foremost, Guo said he will oversee the creation of a new body which will implement short selling in China, called the Centralised Securities Lending Exchange (CSLE).

From a market perspective, the news has been very warmly welcomed. The ability to short sell will open the door for fund managers to hedge their risk and diversify profit streams. It could also shake a few corporates with wanting governance records to up their game – being the victim of a legitimate short selling attack is not an enjoyable position to be in.

And, in a rather cute move the CSRC has structured the CSLE in a way that ensures it earns some pennies from the bourse while remaining in full control of oversight. The CSLE will make shares available to qualified fund managers based in China who want to borrow them for a fee. The shares will be obtained from domestic banks, insurance companies, and fund manager willing to lend them (they will also make money on lending them out).

This structure will allow the CSRC to carefully control the rate of growth of this potentially dangerous market.

The CSRC also revised rules for information disclosure by companies listed on ChiNext, the Shenzhen Stock Exchange’s portal for up and coming Chinese corporates.

ChiNext has had more than its fair share of governance issues with the companies that have listed on the bourse, with plenty of cases of poor corporate governance on behalf of the listed companies and rampant speculation on behalf of investors. The revised rules require all companies that are listed on the exchange to disclose non-financial information, including their key business performance indicators, research and development budgets, core advantages and potential internal and external risks.

More importantly the CSRC has asked all ChiNext-listed companies to disclose their dividend policies and dividend records for the last three years and request that they all set up a system to register individuals who have access to privileged information that could influence stock prices. The timing on these new disclosure policies is unclear, but most observers are convinced this will come into play shortly.

The revision is aimed at encouraging listed companies to make reasonable payouts to shareholders and at tackling insider trading and market manipulation, said a CSRC official in January.

The stock exchange has been stung by criticism that excessive speculation and unreasonably high price-to-earnings ratios abound. The sharp movements in the prices of ChiNext-listed stocks have also triggered investor concerns about insider trading and market manipulation.

“There should be a requirement for dividends; at the very least it needs to be encouraged. Without dividends you can just make up your profits; you can have receivables more than the sum of your revenue,” said Ken Peng, China economist for BNP Paribas.

The news is positive as it should create a culture of good corporate governance that instills greater confidence in institutional investors. Combined with the promise of short selling, mischievous corporates have less room to play.

Introducing better reporting techniques is a good step. But strategists rightly believe there need to be better standards at the root and branch if listed companies are to gain the full favour of investors.

“There really needs to be a stronger approval process before the companies get listed and a more defined exit strategy in place so if you don’t meet the requirements the exchange can kick you out,” says Peng.

In your debt

But improving standards in equity markets alone is not enough; more bond market development is also required.

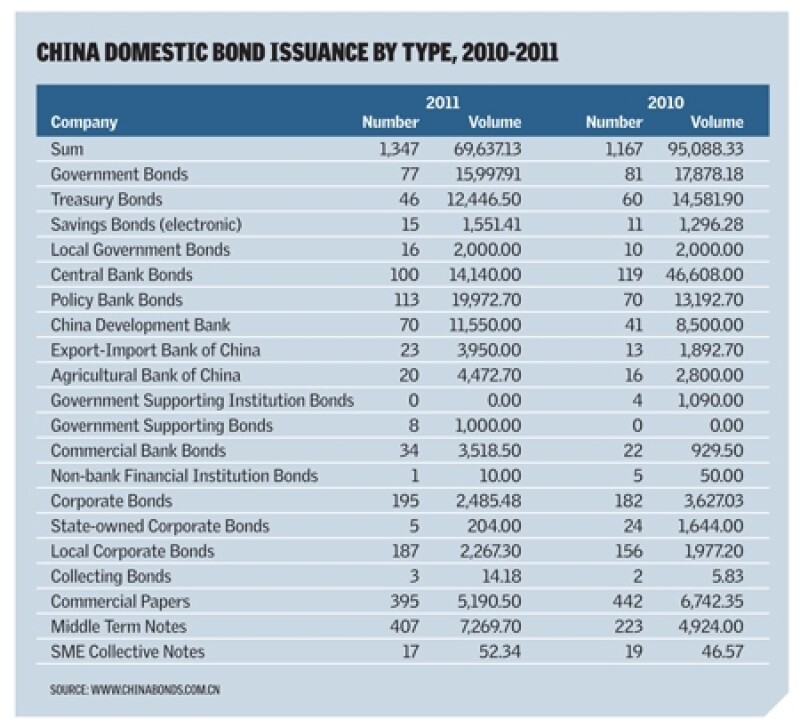

The country’s debt markets have been long ridiculed for lacking depth, with investors outside of financial institutions having restricted access to it.

In fairness Beijing has been slowly opening its doors to more investors. The most recent news in January concerned a new round of renminbi qualified foreign institutional investor, or RQFII, licenses being doled out to offshore asset managers. These licences allow investors to invest a fixed amount in China’s capital markets.

But, as is typical in China, you don’t get something for nothing. The licences require asset managers to invest a minimum of 80% of their assets into mainland debt instruments. That might be a restrictive stipulation, but it’s also a clear bid to improve the depth and liquidity of the country’s local debt markets.

China International Capital Corp., as well as firms including Haitong Asset Management, CITIC and Everbright, have each been assigned investment fund limits of Rmb900 million. Meanwhile E Fund was allowed to raise Rmb1.1 billion and Guoyuan Asset Management and Huatai Asset Management received asset limits of Rmb500 million apiece.

The parties can use the funding to invest in onshore securities products, and further act as a conduit for retail investors looking to access the China market.

It’s a good means to introduce foreign asset managers, even if they are the offshore units of local firms.

Michael He, chief investment officer of China Universal Asset Management – which has just made its RQFII fund available for subscription – said in a statement that “the yields of bonds in the mainland market are higher than the similar securities in the offshore market. In addition, as inflation starts to moderate, reserve requirement ratios for banks as well as interest rates may be lowered, offering an ideal opportunity for bond investments.”

But China is mistaken if it expects these new licences to meaningfully impact local bond spreads and levels of issuance.

“The government’s quota for these funds is so small compared to the much larger bond market,” a RQFII holder tells Asiamoney.

The entire RQFII quota is understood to be Rmb20 billion (US$3.2 billion). China's SAFE set a Rmb10.7 billion investment quota for the first 10 RQFII holders in December 2011, and the second quota of Rmb9.3 billion was approved in January.

Catch-22

There are better solutions to easing the shallowness of China’s bond market than merely flooding it with new asset managers with fixed investment mandates.

A good development would be improving the ability of investors to hedge their bonds. Unlike banks, which are used to debt exposures to companies, asset managers are not usually too happy to dive into many investments without having credible hedging options. In other words they need credit default swaps (CDSs), or at least bond futures.

The chatter that bond futures will return to the market is a positive sign. But how long this takes is unclear.

With bond futures as of yet a theory, China does have CDSs. The instruments, which act as a form of insurance on bonds, were introduced in 2010. But there’s a problem: very few institutions are using them to hedge.

The reasons for this lack of appeal are not totally clear. But it’s likely that the fact that Chinese banks are the biggest buyers of bonds in the country plays a major role. As well-capitalised institutions these lenders appear to feel that they have no need for hedging tools over their bond exposures.

As Asiamoney has argued before, non-bank firms need more access to tap the bond market and have the power to sell credit protection. The more asset managers, insurance companies and securities firms that are given a role in this, the more the credit tools will be used.

That in turn will promote liquidity in the bond markets too.

There is at least some hope in this direction. Towards the end of January, the National Development and Reform Commission, a senior policy-making body, announced a set of plans to make Shanghai a hub for renminbi trading, clearing and settlement and an international finance centre by 2015 and 2020, respectively. The desire of these goals is both to push China’s financial influence in the world and to lay more groundwork for easing out its capital controls.

The primary emphasis on this push is currency trading and allowing foreign companies to list shares in Shanghai. But onshore bonds would likely be a beneficiary of increased renminbi trading and the hedging that this would like entail – particularly if foreign investors are allowed to participate in a less restrictive manner than current QFII licences allow.

We’re all good friends

While the government and CSRC’s Guo appear to be earnestly developing the country’s capital markets, the speed at which it can do so in the bond market especially is likely to be curtailed by the Byzantine world of China’s bond market supervision.

Oversight over the country’s bond market has been long fractured between several different regulators. The People’s Bank of China, for example, oversees the interbank market, while the CSRC looks after corporate bonds, and the China Insurance Regulatory Commission oversees the insurance companies that buy much of the country’s debt.

Breaking up this power may have made sense once but it does not do so anymore. If the country’s bond markets are to offer would-be corporate spenders more funding options, Guo needs the various regulators to feel comfortable that their respective areas of interest – insurance, asset management, etc – are being well protected.

It’s important that this happens. The country’s regulators are notoriously territorial and jealous of their rivals. However they need to work together to ensure that China’s economy has the most funding options available to avoid a hard economic landing.

Banking and securities regulators cannot alter the course of China’s economic path alone but they are capable of creating an environment best able to support growth.

There are some signs this is happening. The new chief of the China Banking Regulatory Commission, Shang Fulin’s first step was to postpone three regulations that would see banks take on Basel III-esque capital standards.

This gives China’s banks more breathing room and further incentive to find way to help the economy. Combined with regulatory improvements in the capital markets, China is definitely showing signs of financial foresight.

More will be needed. While the heady days of 10% annual economic growth may be over, China still has a lot of expansion potential. But the country’s leaders must ensure that its capital markets grow at least as fast as its economy.

Bank lending cannot and should not do everything in China; it’s time the equity and especially bond markets played more of a role.