Not that long ago the world was talking about Chindia, or how the two most heavily populated countries on earth would come to economically dominate the 21st century.

No longer. China has outpaced India in many ways, but none is more obvious than in the way the two are viewed by the international credit ratings agencies.

While Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch view China to be worthy of Aa3/AA-/A+ ratings, India only merits ratings of Baa3/BBB-/BBB-. The world’s second-most populous nation and Asia’s third-largest economy is sitting one precarious notch above junk credit status.

A host of reasons is to blame for the country’s lower position: debt-laden corporates, a stuttering reform process, billowing corruption and sluggish growth. But top of the agenda for policymakers has been persistently high inflation.

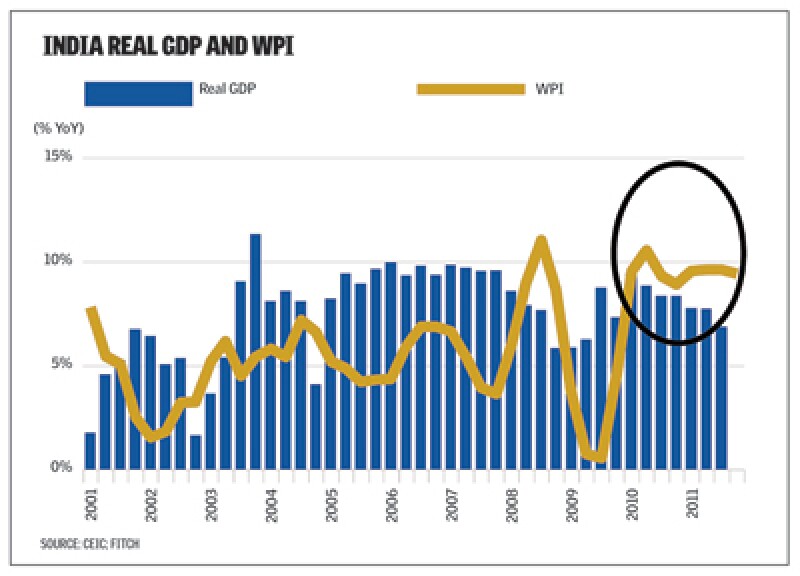

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has increased its policy rate 13 times since April 2009 to 9.5% to combat rising prices. It’s beginning to work, with wholesale price inflation (WPI) dropping from 7.47% in late 2011 to 6.55% in January, but it’s still fairly high.

If India gets inflation in hand it could yet enjoy improved growth and stability. But it would not take much for the economy to slip the other way, potentially causing a downgrade. That would lead to further downgrades as the country’s sovereign ceiling was lowered; bond yields would widen dramatically across the board; funding costs for India’s increasingly indebted corporates would increase, putting pressure on its poorly capitalised banks already struggling with asset quality; and the RBI’s efforts at curbing inflation would be hamstrung.

In other words: a painful outlook for all concerned. India’s government would do best to avoid it, if it can.

An uncertain outlook

Optimists argue that it’s unlikely that India’s credit rating will drop to junk in the near future.

While the country is rated ‘BBB-’ by all three major credit-rating agencies, all have a stable outlook on the credit.

Moreover, most analysts believe that the coming months will see India’s economic outlook improve. They predict that the country’s cyclical downturn is at an end, monetary policy will begin to loosen and GDP growth will pick up on the back of lower interest rates. New Delhi would certainly agree with such projections, while India’s central bank would no doubt note that inflation is coming under control.

But India is vulnerable, as the performance of its currency and stock market last year revealed. Renewed eurozone debt problems or a downturn in the US or Chinese economies, could cause another capital flight from India. So could local market volatility.

On February 6, S&P released a report noting that it believes the balance of risks behind its stable outlook on India’s rating may be shifting.

“This shift is slightly toward the negative for reasons including: high inflation, a weak government fiscal position, and slower economic growth,” says the report, headlined by Singapore-based primary credit analyst Takahira Ogawa. “These factors in turn have reduced investor confidence in the Indian rupee and triggered capital outflow, resulting in depreciation against major currencies.”

“And uncertainty in global financial markets and European sovereign debt problems could add to the pressures India is feeling,” the report added.

About a week prior to the S&P research, Nomura’s credit sales and trading desk released a report disseminated to institutional investors which mentioned a “fat-tail risk of a sovereign rating downgrade” as a reason for the bank’s underweight position on Indian bank credits.

“The current economic downturn seems to be cyclical rather than structural,” said the India portion of the report, written by analyst William Mak. “However, if inflation remains structurally high as our economists expect, the fiscal deficit situation worsens further, or the banking system faces more stresses, then there is a real risk that the sovereign could be downgraded.”

Macro concerns

There are a few factors underpinning these anxieties. Firstly, economists remain unsure whether India’s inflation figures truly have turned around as much as the country’s policymakers proclaim.

The problem is the latter’s use of WPI data. Consumer price inflation (CPI) is the more commonly used measurement in other countries because it encompasses a broader basket of goods than WPI, and captures prices at retail rather than wholesale level.

Spurred by the demand for CPI data, the Central Statistics Office began reporting CPI in January this year. Its first report showed CPI at an annual 7.65% for the month.

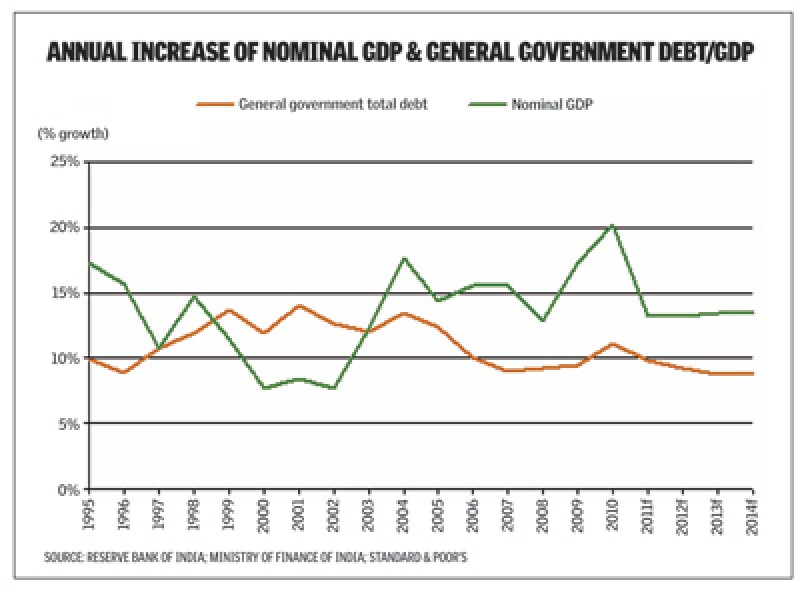

India’s declining pace of growth is also a concern. Growth in gross domestic product (GDP) has tapered off dramatically since hitting an historic high of 11.8% year-on-year in the December quarter of 2003. Average growth since 2000 has been 7.45%. But it expanded only 6.1% in the final quarter of 2011 – its slowest growth since 2009 – and is expected to remain below 7% for the 2012 fiscal year.

While 6.1% may be a dream for the developed countries of the rich world it is not good enough for a resource-rich, heavily populated emerging economy with a burgeoning middle class like India.

Then there’s the country’s external debt position. New Delhi has run a current account deficit since 2004 – it stood at US$16.9 billion in the third quarter of 2011 – but it could historically rely on net capital inflows and foreign direct investment to mitigate this shortfall.

But a persistently bearish environment – combined with a loss of investor confidence in India’s currency – could change that.

“Countries that have current account deficits are net importers of credit so they could be more vulnerable to a sharp rise in global risk aversion,” says Art Woo, a director covering the India sovereign for Fitch. “If you’re a net borrower of credit and that credit becomes more expensive or, worse yet, unavailable then obviously that has an impact.”

Risk aversion led capital inflows into India to drop from US$29 billion in 2010 to a net outflow of US$300 million in 2011. If that continues this year the current account deficit could rise, another negative in the rating agencies’ books.

Also of great importance to the agencies is the ratio between India’s debt and its foreign-exchange reserves. Moody’s noted in its January 12 report that the country’s external vulnerability indicator (EVI) – a measure of whether a country’s FX reserves are sufficient to meet all public and private external debt obligations in the event of an external shock – has been steadily rising.

Back in the 2008-2009 fiscal year, India’s EVI stood at 32.2, which means that its obligations were only a third of its reserves. But Moody’s projects an EVI of 48.4 for the 2012 fiscal year and 54.1 for 2013, more than half of reserves and a reflection of the country’s growing indebtedness.

The value of the rupee is another concern. During a protracted period of volatility in emerging markets last year, the rupee’s value against the US dollar slid, reaching a nadir of INR44.2 against the US currency on July 29, and standing at only INR53.86 on December 11, representing an almost 22% decline in value.

It was trading at INR48.96 as Asiamoney went to press and remains well below the INR30 level it enjoyed versus the US dollar at the beginning of 2008.

A weak rupee is bad because the country relies heavily on commodity imports, which are largely valued in US dollars. A rally in commodity markets combined with a weak rupee spells danger for India.

A combination of rupee weakness and inflation particularly concerns corporates. Indian chief financial officers polled by Bank of America-Merrill Lynch in a survey on February 21 were more concerned about these two factors than the European debt crisis.

Combine all of these issues and it’s evident that India remains in a vulnerable position. It might not take much – a sharp downturn in eurozone sentiment, or perhaps a marked strengthening in the US dollar – to pitch it towards a downgrade.

Details of a downgrade

A downgrade to India’s sovereign rating would have multiple impacts.

For a start – depending on how the rating agencies choose to apply their sovereign ceilings – a sovereign downgrade would be accompanied by downgrades to other credits as well. Stronger corporate credits such as Reliance Industries may survive the axe but financial institutions – particularly state-owned ones – would be at great risk of downgrade.

This would prompt a flight of foreign investor capital. Foreign investors who can only keep their money in investment-grade bonds would need to pull out of the sovereign’s debt as well as that of its banks.

That would cause bond spreads to widen, sparking a broader sell-off. The funding squeeze would put pressure on banks and corporates, and likely cause a downturn in the stock market.

Of particular danger would be the impact of a downgrade on India’s monetary policy.

“The most important [issue] is the limited ability of the RBI to cut rates,” says Daniel Tabbush, CLSA’s regional head of banks research. “Once [a downgrade] happens, you'll probably have capital flight and they may have to actually raise rates in that environment.”

More monetary tightening would be bad news for India’s banks in particular. It could derail the analyst consensus of improved growth and stability of the lenders and start a domino effect of higher credit costs, non-performing loans, deteriorating asset quality and government intervention.

The country’s banks are already facing pressures. In October last year, Moody’s downgraded the financial strength of India’s largest bank, the State Bank of India (SBI), by one notch to D+ on account of the lender’s low tier-one capital ratio and deteriorating asset quality.

“Our expectations that non-performing assets are likely to continue rising in the near term – due to higher interest rates and a slower economy – have caused us to adopt a negative view on SBI’s creditworthiness,” said Moody’s Beatrice Woo in a press release accompanying the ratings announcement.

On January 31, New Delhi announced that it would inject INR79 billion (US$1.6 billion) into SBI to recapitalise it in the face of its deteriorating asset quality. The bank followed this with an earnings announcement on February 14 reporting record non-performing loans (NPLs) of INR400.98 billion and a doubling of the provision for future bad assets.

Moody’s is concerned that the current capitalisation of Indian banks – which averages 9.2% and is one of the lowest in the region – is not enough to sustain the industry, given its deteriorating asset quality. Banking systems in emerging economies need strong capital positions to act as a buffer against credit growth and NPLs.

“With [the] current capital level, we project a decline in [the] core tier-one capital ratio to below 9% by fiscal year 2013,” the agency said in a November 9 outlook report, which it still stands by. “As such, we believe Indian banks will need to raise fresh core tier-one capital to support loan growth and to build a cushion for Basel III [global capital-adequacy] norms.”

Nomura’s Mak believes that a sovereign downgrade could blow Indian bank’s US dollar bond yields out by 300 basis points from where they trade today. SBI’s bonds maturing in 2015 were trading at yields of 3.94% as Asiamoney went to press.

“If the sovereign rating is downgraded, then it means the economy itself is not good so that could have implications for [banks’] asset quality as well,” Mak adds.

Corporate calamity

India’s corporates would also feel the strain of a downgrade. That’s a worry, given that corporate debt is rising and some companies are facing payment problems.

The Finance Ministry’s most recent report on India’s external debt position stated that the nation’s external debt stock surged by 17.2% in one year to US$305.9 billion at the end of March 2011, an increase of US$44.9 billion over March 2010.

Corporate borrowing now accounts for 28.9% of that total – US$88.7 billion – as compared to 19.7% in 2005. This is a sizeable sum.

As Asiamoney revealed in its February cover story, several companies are struggling to find the money to repay maturing foreign-currency convertible bonds (FCCBs), due in part to overall indebtedness, improper hedging and the massive decline in both the rupee and Indian equities.

In total, 72 FCCBs worth a combined US$5.8 billion come due in 2012. Kotak Institutional Equities believes that 15 FCCBs issued by 11 Indian corporates that mature this year have a high probability of default.

FCCBs aren’t the only problem. Aviation companies are also struggling: Air India and Kingfisher Airlines are trying to restructure their debts – and the latter’s reclassification as an NPA is a major reason for the gigantic hole in SBI’s balance sheet.

The telecommunications sector could also face difficulties after the scandal over the doling out of second-generation mobile licences saw hundreds cancelled by the Supreme Court in January. This was unwelcome news for an industry already immersed in a debilitating price war.

In fairness, most companies could weather a sovereign downgrade. “The borrowers in India [would] have to resort to local bank lending, local asset management lending, local insurance company lending, so the cost of funds goes up but I think replacement [lenders] could be found,” says a debt capital markets (DCM) head at an Indian bank.

But a re-pricing of corporate debt would occur, exacerbating existing indebtedness and potentially NPLs.

“You will certainly see much higher risk of defaults because interest coverage will worsen for the companies [in troubled sectors] so bond issuers will see rising funding costs and it certainly means NPL trends will continue to rise,” says Tabbush. “NPLs for the state banks could rise by more than 100%.”

He notes that there has been talk about the RBI potentially making banks lower their loan rates, something it could do most easily with state banks such as the SBI.

“Then you’re talking about a very Japanese scenario where you’re supporting companies with [low] interest and you’re not going after shareholder value and not supporting returns. Then NPLs could rise by even more than 100%,” he says.

All change?

To minimise the possibility of a ratings drop, and ideally strive towards an upgrade instead, Indian policymakers need to unite the electorate and political establishment behind a requisitely bold policy and reform agenda. That may be easier said than done, but it’s the only way the country can regain its rightful place as a leading growth economy of Asia.

India needs to use both monetary and fiscal policy levers to reform the economy in a way that makes it less prone to external risks. Slow growth needs to be addressed via microeconomic and structural reforms that deregulate sectors weighed down by red tape, pave the way for more rapid infrastructure development and minimise corruption. Policies friendly to foreign investment should be encouraged.

New Delhi also needs to stick to its fiscal consolidation plans and reorganise its budgets in a way that mitigates the rising public debt. In order to do this it should reduce subsidies and introduce the long-mooted goods and sales tax.

Inflation needs to be tamed by a faster unwinding of the fiscal stimulus put in place after the global financial crisis. Growth needs to be rooted in domestic consumption, not government stimulus. And India needs to put more work into developing its own natural resources to counterbalance its reliance on foreign commodities.

Finally, oversight is needed to make sure that corporate indebtedness does not get out of control and the government should not lean on the banks to offer cheap credit for local corporates. That would be anti-competitive and lead to poor asset quality and poor returns for foreign investors.

Will it take such steps? It doesn’t appear likely. And if New Delhi doesn’t opt to do any of the above, a downgrade might prove merited. As one banker Asiamoney spoke to quips: “A downgrade would be a salutary kick in the shins”.

India’s borrowers and investors alike will hope that it doesn’t come to that.