Seoul is reaping the rewards of its own burst property bubble.

Four years ago, housing prices in the metropolitan area of the South Korean capital stood at record levels, the culmination of eight years of increases. But as much of the world has discovered in the years since 2008, property prices can go down as well as up.

Increasingly unaffordable home valuations combined with government-initiated measures to prevent speculative buying have cooled purchasing appetite. Housing prices have slumped 0.7% this year after growing 0.3% in 2011, while residential property deals in the greater Seoul metropolitan area dropped nearly 40% in the first three months of the year. The Bank of Korea forecasts that home prices will keep dropping as the credit crisis in Europe hurts export businesses and curtails consumer spending.

That is worrying for Korea’s banks, which have financed most of the housing market and increasingly relied on its income streams. Mortgage loans reached a record 66% of total lending to households last year, according to central bank data.

The Financial Supervisory Service (FSS) has warned banks to raise loan provisions as a buffer, especially because it expects bank delinquency ratios to rise amid concern that the global economy is not on a convincing path to recovery.

“Because Korean banks can be affected as the global financial crisis continues, we’ve asked banks to raise their provisions and the amount of bad debt they can charge off their books in advance so that they can absorb losses,” says Kwon Chang Woo, head of the bank supervision department at the Seoul-based financial regulator.

The country’s top banks acknowledge the need to beef up the books, especially as global risks continue to weigh on property prices and hurt borrowers’ ability to meet debt payments.

“We’re taking a more conservative approach when calculating how much in provisions we have to raise,” says Lee Young Gyu, a spokesman for Woori Bank. “If we see a tsunami of risk like what we saw during the Asian financial crisis, of course things will be hard. But for now I think we have enough funds to buffer a shock.”

A KB Financial spokesman also admits that the bank is raising additional funds and that if risk factors continue, it will respond by stocking even more.

Building up financial ammunition will come in handy since more borrowers have already began defaulting on their loans. According to FSS data, bank delinquency ratios have risen to 0.97% this year, the highest level in nearly six years. Defaults on mortgage loans this year also rose 0.64%, the highest level since 2006.

The FSS’s Kwon says he is confident that bank delinquencies will not rise beyond 2% this year. But investors are less optimistic.

Kee Ho Sam, head of Seoul-based Dongbu Asset Management’s equity portfolio, which includes Woori Finance Holdings shares, estimates that KRW4 trillion (US$3.48 billion) of principal payments on mortgage loans are due this year. He thinks that deteriorating property valuations will inevitably boost delinquencies.

“All this money is due at a time when the property market is not doing so well, which will hurt the mortgagors’ ability to pay back since they can’t sell these homes. If things spiral out of control, [for the banks to try] raising provisions will do little to help the situation,” says Kee.

Meanwhile Korean households are already heavily in the red, while the government is pressuring the banks to lend to lower income groups. The pressure on Korea’s banks could prove costly.

Feeling the pinch

As things stand, South Korea’s main lenders are well-capitalised in anticipation of Basel III.

The Tier I ratio of KB Financial Group, owner of KB Kookmin, was 10.29% as of the first quarter of this year and its core Tier I ratio was 10.22%, above the new 8.5% Basel requirement to be implemented by 2019.

Woori Bank, a unit of the nation’s largest financial holding company by assets, had a 10.77% Tier I ratio as of March, while Shinhan Financial Group, South Korea’s largest financial company by market value, recorded 12.34%.

But while the banks may boast capital, their balance sheets are feeling the pinch.

Shinhan Financial Group said its net income in the first quarter fell 11% because it had to set aside 45% more funds compared to a year earlier to cover potential loan losses. Its non-performing loans (NPLs) rose from 1.25% in the fourth quarter of 2011 to 1.45% in the first quarter.

KB Financial Group saw a fifth of its profit slashed during that same period after it had to earmark 75% more in provisions on household debt. Its NPLs rose 21 basis points (bp) to 1.64% in the first quarter of the year. Mortgage loans account for 45% of its total bank lending, leaving it particularly vulnerable to a dip in housing prices.

Despite this, a number of analysts are confident that the country has its mortgage loans under control and that they will not affect bank liquidity.

“This is not a systemic risk to the economy because the government still has stringent measures on mortgage lending,” says Sharon Lam, an economist at Morgan Stanley in Hong Kong. “Mortgage asset quality is still very good so there is no problem with mortgage loans.”

Others are less sanguine. Park Chang Gyun, a finance professor at Seoul’s Joongang University, believes delinquencies haven’t shot up because Korean banks only require borrowers to pay interest on their mortgage loans, not the principal. As of the end of June 2011, 78% of Koreans who took out loans were only making interest payments, according to a Moody’s report published last month.

This is not a problem while property prices rise, but debtors cannot use rising house prices to pay off loan principal in a housing slump.

“A system where borrowers just pay off interest is very dangerous to the banking system,” says Park. “The reason why this [interest payment-only loans] was sustainable in the past was because property prices were able to rise, which alleviates the burden of principal repayments due at maturity. But the days of using profits from rising property prices to pay off debt is over.”

Households in the red

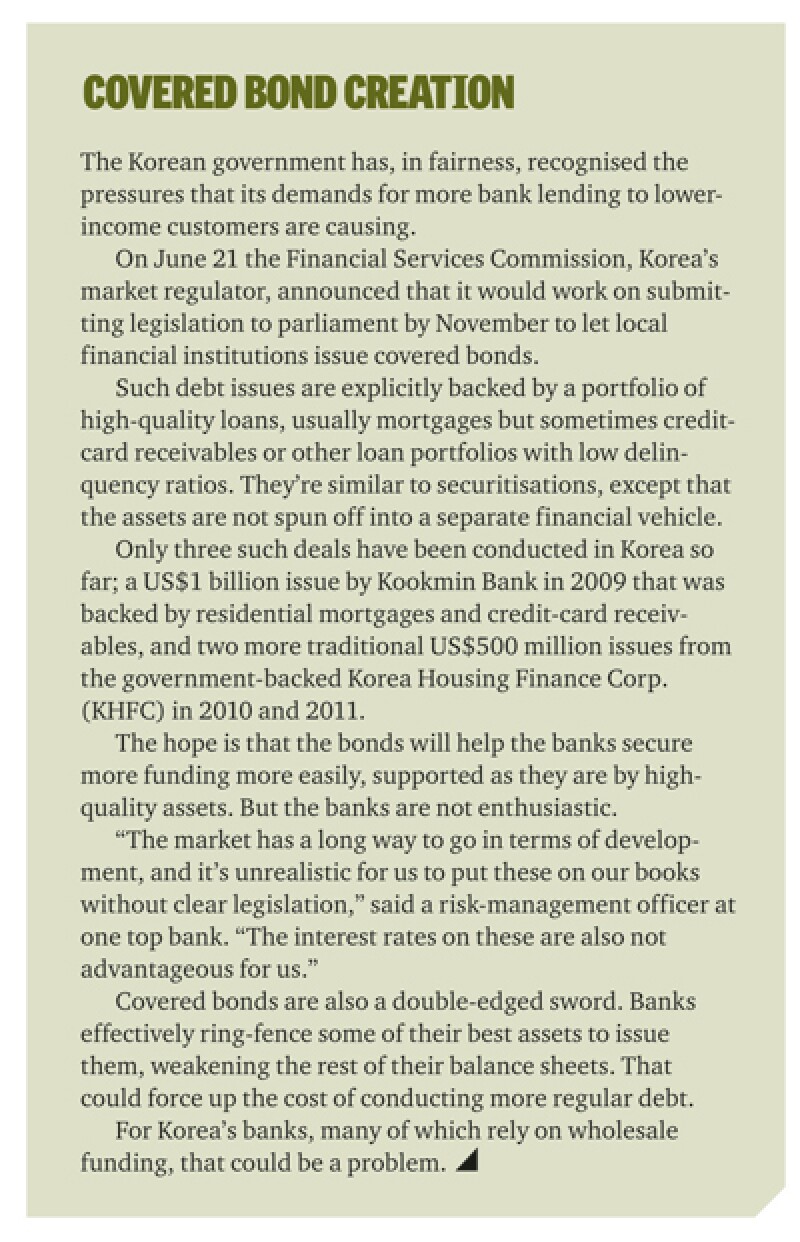

It’s not just mortgages that are the problem. Korean households are in general indebted to the hilt, leaving little margin for error.

According to an Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report published in May, average household debt stood at a whopping 154.9% of disposable income in 2011, a level higher than Greece, which stands at 97.8%, or Spain, where it is 140.5%.

Korea is one of the few countries to have seen this figure climb since the onset of the 2007 global financial crisis. Its household debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratios remain slightly lower than the US at 89%, but should overtake it next year, predicts the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS).

Moody’s describes the rate of household debt increases in Korea as alarming.

“These household loans have characteristics that make them vulnerable to financial shocks and tail risks arising from the European debt crisis and China’s economic slowdown, leading to a deterioration in loan performance,” it said in a June report.

The Korean government has acknowledged that household debt levels are a problem. It is particularly worried about how quickly lending from non-financial institutions to low-income borrowers and senior citizens is rising. In an April report it noted that such lending comprised 39.6% of credit growth in Korea as of the end of last year.

This is particularly concerning because of the interest charged on such loans. Non-financial institutions – typically mutual savings banks and mutual credit companies – charge an average rate of about 24.4% on unsecured loans, compared to the average 9.8% banks charge.

In response to this borrowing trend, the FSS said last month that it would ask banks to distribute more loans to this group of lower-income and low-credit borrowers with interest rates at around 10%. On July 12 it followed by saying it would crack down on banks who don’t give out these loans, singling out Hana Bank and Korea Exchange Bank as well as foreign bank branches such as Citi and Standard Chartered.

“If you look at their [lower income and senior citizen borrowers’] ability to pay back on a scale of one to 10, with one being the highest, we’ve seen that their credit quality ranges from five to eight,” an official at the Seoul-based Financial Services Commission tells Asiamoney. “The challenge is to make sure our policies are working faster than the rate of loans being given out.”

For Korea’s financial regulator to ask banks to lend more to borrowers of lower credit quality is, at the very least, ethically dubious.

It risks hurting their performance, raising the need for more provisions against potential bad debts and reducing profits at a time when pressure is being brought to bear to cut overall loan risks, raising bad debts and hurting bank balance sheets.

“If banks don’t want to lend, they don’t want to lend. If you’re twisting their arm, I would be concerned about that for other reasons. That is not good for the commercial standing of the banks. I don’t find all of this too convincing,” says Erik Lueth, chief economist at RBS in Hong Kong.

Bad news abounding

A soft property market, the indebtedness of Korea’s households and the call to lend more to weaker customers makes for an unpleasant cocktail that could easily leave Korea’s banks facing more bad debts.

It’s particularly ill-timed, given market conditions and bank circumstances.

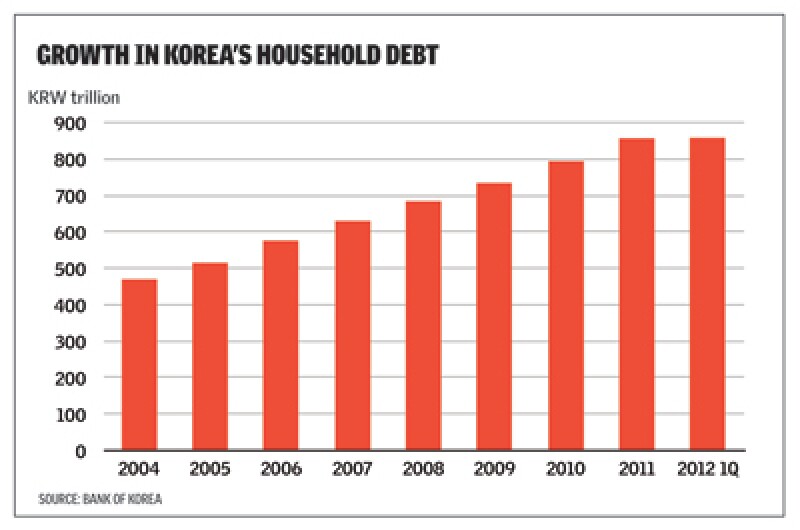

Because many Korean banks do not cover their lending with deposits, they raise funds in the international bond markets to cover the difference, which – along with foreign deposits and federal funding – is commonly called wholesale funding.

KB Kookmin’s loan-to-deposit ratio was 97.4% in the first quarter, while Shinhan and Woori booked a respective 97.2% and 95.8%. A 100% ratio means loans to deposits are equal. South Korea’s foreign-currency liquidity ratio was 108.3%, the highest since at least 2009. However, Korean banks are paying creditors more to borrow foreign currency. The spread on borrowing costs widened to 25.6bp in June, the most so far this year, according to FSS data.

The eurozone crisis has already left investors increasingly risk averse. Add into that rising NPL levels, and Korean banks’ costs of funding could quickly rise.

“If there is a major event from Europe, it may be difficult for these banks to roll over or obtain more funds from foreign creditors,” warns Choi Young Il, a banking analyst at Moody’s Investors Service in Hong Kong. “Countries like the Philippines and Taiwan are in a better standing because they have much more foreign liquidity onshore.”

Having to raise more capital would also hurt bank shares, which for the top three have already fallen by an average 23% over the past year. Bond spreads for these banks tightened more than 100bp so far this year as investors bought Korean bank credit over those issued by European and US banks, which have been shunned by risk-averse investors.

Bank analysts are not optimistic of a turnaround. Woori’s research analyst Choi Jin Seok downgraded his outlook for domestic banks for the rest of the year, citing Europe, domestic household debt levels and new Basel requirements as obstacles to growth. Sung Byung Joo of Tong Yang Securities says unless the household debt issue shows signs of improvement, investors should sell bank shares, at least in the short term.

Financial industry participants believe that the only way the outlook for Korean banks will improve is if Korea’s property market rebounds or if the global economy gets back on track. Neither looks likely any time soon.

Korea’s central bank lowered this year’s GDP forecast to 3% from a previous estimate of 3.5% on July 13, the same day that it unexpectedly cut interest rates to 2% for the first time since February 2009 to boost growth. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) cut South Korea’s annual growth forecast for this year to 3.25% from 3.5%, citing substantial uncertainties in the country’s outlook if the Europe problem continues to spill over to the US and China, Korea’s largest export markets.

Bookyum Kim, research analyst at Consus Asset Management in Seoul, thinks the situation will become quite serious for banks if the economy and property market do not turn around by mid-2013. But with the Federal Reserve cutting its annual growth forecast for the US to as low as 1.9% this year and China’s GDP growing at its slowest pace in three years in the second quarter, the prospects of Korea’s economy recovering this year look dim.

“Prudential regulation can only do so much. That’s not only true for Korea but true in general,” Lueth says. “The problem is the economy is very vulnerable so if we have a major shock from Europe and growth goes to 2%, household debt could become an issue. There are huge downside risks right now and that situation makes Korea very vulnerable.”

Kim Jung Shik, an adviser to the Financial Services Commission and professor at Yonsei University, tells Asiamoney the best way is for the government to help spur jobs, but that won’t work at a time of crisis.

“We can’t really put out a stimulus package either like we did in 2008. Back then, China was doing alright so that did help boost exports. But with China and the US where they’re at, it’s not going to work this time around.”

Finding the funds

In the absence of macroeconomic improvement, Korea’s banks look set for taxing times.

If housing prices continue to slip and some of the banks’ new, less reliable customers are unable to maintain loan payments, their NPL levels will keep rising, causing stock valuations to keep falling and their cost of debt to mount.

Such a rise in troubled loans is unlikely to prove fatal for any of the banks, all of which are still well capitalised and are making money. But it could crimp their performance and cause their capital ratios to slip.

That may force some banks into the market for equity, diluting their existing shareholders, while their bond spreads would likely widen too, making wholesale funding much more expensive. Bank analysts and portfolio managers are already flashing red signs, which may prompt investors to think twice about buying their stocks or bonds.

While it’s summer in Seoul, Korea’s leading banks look set for some unpleasant weather.