On July 31, half of India’s 1.2 billion population was abruptly left in the dark. The largest power blackout in history left most of the country’s 21 northern and eastern states without electricity.

Thousands were stranded at cross-border train stations, and in the capital New Delhi, paralysed subways triggered hours of traffic congestion. It was the second power outage in two days.

India’s citizens are long-used to sporadic electricity cuts and rely on generators, but the scale of this latest power failure prompted widespread anger against the Congress-led government. Yet a day after the blackout, India’s power minister Sushil Kumar Shinde was promoted to home minister.

Within 24 hours, the government’s failure to invest enough into the economy had been laid bare, alongside its willingness to promote favourites irrespective of performance.

The failure of India’s electricity grids was not surprising. The country’s power industry is saddled with billions of dollars of debt due to the government insisting most companies keep tariffs at rock-bottom levels. Added to this, the rupee’s record-low valuation against the US dollar this year has driven up the cost of coal imports, further increasing the costs of power generators. Mounting losses have left them unable to upgrade equipment to cope with mounting power needs.

The consequences are clear; ramshackle infrastructure has contributed to India’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth slowing to an annualised 5.5% in the April to June quarter of this year – near a nine-year low and way below 9% the government wants.

It could spell disaster for the country’s banks. They have lent heavily to power generation and distribution companies, and face bad debts if they default. Add a slowing economy and incoming Basel III capital requirements, and it’s little wonder banks are wary of putting more money into infrastructure.

The government is, however, announcing ambitious investment goals. In his Independence Day speech on August 15, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh pledged that all Indian homes would have access to power by 2015 and that US$1 trillion would be spent on improving infrastructure by 2017.

To approach such an amount, New Delhi needs to persuade local and international investors to invest enormous sums into a troubled sector. Yet foreign direct investment (FDI) is dropping, shrinking by 67% to US$4.43 billion in the three months to June compared to a year earlier.

Investors are particularly leery of the power sector, discouraged by popularity-obsessed politicians’ control over tariffs, the indebtedness and inefficiency of infrastructure companies and an ailing economy.

“The hurdles are causing private equity to step back,” says Sanjiv Aggarwal, Mumbai partner of UK-based private equity firm Actis. “We are not invested in any project based on imported coal that has no ability to pass on the cost due to the depreciating rupee.”

India’s government must act fast if it is to source funds to upgrade both power and infrastructure. Firstly, it must ensure projects are financially viable, principally by raising the amounts that infrastructure operators can charge customers.

Additionally, the country needs to entice investor funding into infrastructure projects. Its nascent bond market could offer dearly needed cash, but only if the government makes genuine reform efforts.

Stretched for cash

The power sector lies at the heart of India’s problems. Coal from the government-controlled Coal India and the smaller state-run Singareni Collieries fuels more than 60% of India’s power plants, leaving them exposed to commodity price changes. The country’s coal industry was nationalised in 1975 to reflect this importance, and demand for coal is mounting. But new mine approvals are unpopular with the farmer vote that government officials court, which has limited state-run Coal India’s ability to raise output.

Instead it has had to import coal to meet demand. This has become increasingly expensive as the rupee reached record lows against the dollar in July, and with Indonesia and Australia slapping new taxes on coal exports.

Despite rising costs, most power generators have been unable to raise fixed contract prices with public electricity grids. This has led them to lose money and reduce output. As a result, 15,000 megawatts (MW) of power-generation capacity lies idle due to fuel shortages, and many plants are running below capacity.

Tata Power’s US$3 billion Mundra plant in Gujarat reported an INR18 billion (US$323 million) loss for the three months to March, while Reliance Power may lose its 4,000 MW Krishnapatnam project and a INR3 billion bank guarantee after a court rejected its plea to raise tariffs.

Generation companies have also had to borrow to cover losses. Kotak Mahindra Bank, for example, estimated that its power-generation lending hit INR2 trillion as of March.

The country’s state electricity boards (SEBs) are in equally bad shape, with cheap tariffs leaving them saddled with US$35 billion in debt, or effectively bankrupt. They tend to delay payments to power generators, adding to financial pressure on the latter and forcing them to borrow more.

Power suppliers have INR5.3 trillion in outstanding project finance loans, and concerns are mounting that they will begin to default.

“The private guys are still officially maintaining the stance that all is fine, there’s no problem, but… there is a lurking fear that… they will come to the table at least for restructuring, or say that they will not be able to pay the loans back,” said a Mumbai-based power analyst at a global bank.

HSBC said in a June report that it expects Tata Power’s net profit to decline by 5% more than estimated in the financial year ending in 2013 and Adani Power’s by 20%, adding that hurdles on coal will squeeze supply for another decade. These are not isolated examples.

Given this backdrop, it’s little wonder that private investors aren’t keen. An August 23 report by the Reserve Bank of India said that private infrastructure investment collapsed to INR1 trillion in the 12 months until July, versus INR2.2 trillion the year before.

Tackling the problems

This messy situation requires concerted reform – something the Congress-led government has been unwilling or unable to deliver.

Almost everybody Asiamoney spoke to agrees that India’s power industry will only flourish if the sector is privatised so that politicians cannot manipulate it.

“You need to run the state electricity boards like an enterprise. It’s because you have government officials at the top,” says Surendra Rao, former chief of the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission. “Until you make it financially attractive I doubt foreign investment will come in a big way.”

As part of this process, New Delhi needs to let state utilities charge higher tariffs, which Rao says amounted to INR1 trillion (US$18 billion) in the past decade. Otherwise power producers will start defaulting on debt.

India’s states are not blind to these problems. Tamil Nadu raised tariffs 37% this year to improve India’s effectively bankrupt SEBs. In addition, state governments and banks will each take half of the boards’ liabilities for seven provinces.

This should restore some harmony to the power suppliers’ balance sheets and prevent the SEBs from mass debt defaults. But there is a cost too; a proposal by central and state regulators in May warns that shifting the SEB debts could hurt state finances and be “detrimental to the overall financial health of the banks”.

Again, raising tariffs offers a better solution. HSBC power analyst Arun Kumar estimated that India’s largest state Uttar Pradesh needed to raise tariffs by 40% immediately to help its struggling power producers. An HSBC report noted that the state of Kerala should increase tariffs by 50.6% and Jharkhand by 78.1% by next year. All states should raise power tariffs by an additional 5%-7% each year to match rising fuel costs, adds Kumar.

These hikes would help SEBs and power suppliers pass on rising costs to the consumer and make room to cut debt and improve revenue.

Unfortunately consumers will pay more, something India’s increasingly populist state and federal governments are reluctant to countenance.

Looking to bonds

Tariff hikes offer part of the answer, but the power industry also needs fresh funding sources as primary avenues from banks and private equity become harder to navigate.

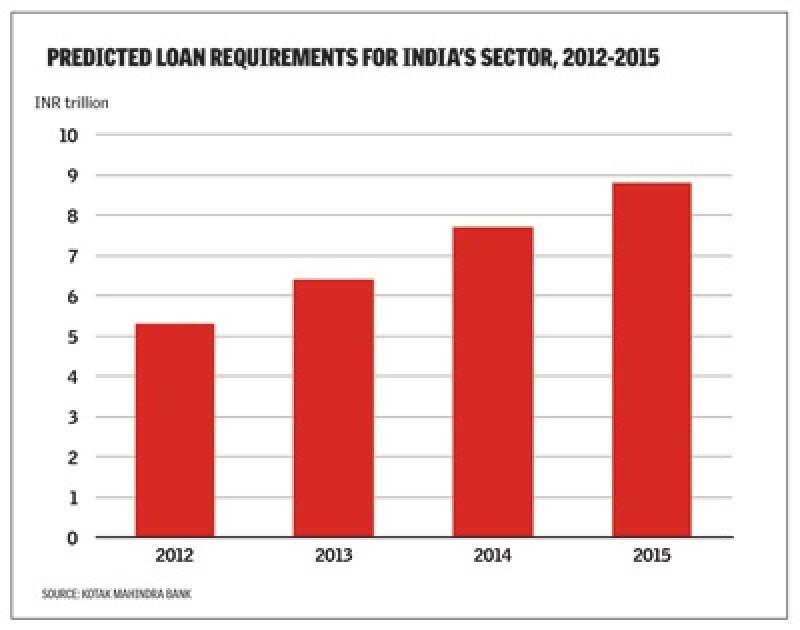

India’s nascent US$890 billion bond market could help. Kotak Mahindra Bank estimates that the power sector requires INR8.9 trillion in bank loans and INR2.6 trillion in bond funding by 2015.

Yet until now India’s infrastructure companies have rarely issued bonds. They account for only 5%-7% of the INR1.72 trillion (US$31 billion) in local- and foreign-currency bonds issued from India so far this year, according to Axis Bank estimates. Tata Power issued its first-ever hybrid bond on August 16 worth INR15 billion at a 10.75% coupon maturing in 60 years.

The reluctance to sell bonds has largely been due to a lack of name recognition or credit strength.

“Bond investors are open to taking project risk, but of course you really need to get into the specifics of each and every project and determine the feasibility of the deals,” says Amit Sheopuri, co-head of debt capital markets (DCM) at Citi.

Only 1% of Indian companies rated by global analytical company CRISIL are ‘AAA’. Internationally renowned companies such as Tata Power, rated ‘AAA’ by Credit Rating and Information Services India (CRISIL), can obtain bond funding with relative ease, but lower-rated companies find it harder to source competitively priced bonds for smaller, sometimes uncompleted power projects.

“On a standalone basis, these projects will have a ‘BBB’ rating or lower, and that’s just domestically. At that [rating] level, the bond market is not there to provide funding. You need to have at least an ‘AA’ rating,” says Paritosh Kashyap, head of DCM for Kotak Mahindra Bank.

Investors looking at high-yield credits are particularly sensitive to the feasibility and risks attached to the borrower’s business model. And again, the dynamics of India’s power sector work against power companies in need of financing.

“It’s not that we can’t do deals for ‘B’ credit; the issue is that apart from ratings, you need to make business cases, which will be hard,” says a head of DCM in Mumbai.

Yet it isn’t impossible. S. Nandakumar, infrastructure analyst at Fitch Ratings, notes that completed road projects with established toll systems that can map out “a realistic forecast of future performance risk” can raise bond funding. Power plants that can do the same might be able to entice investment.

A step up

A good credit rating can help immeasurably when finding bond investors. The only way smaller infrastructure companies needing capital can gain such ratings is with a credit guarantee.

“Credit enhancement is key for developing the bond market. Be it a dollar bond or a rupee bond, the guarantee or credit enhancement is a must,” says Kashyap.

State-run India Infrastructure Company Ltd (IIFCL) and the Asia Development Bank launched one in January, and IIFCL is in talks to sponsor up to US$500 million of debt for three projects by raising their ratings from ‘A,’ ‘A-’ and ‘BBB+’ to ‘AA’. Infrastructure conglomerate GMR’s ‘A’-rated highway project will save up to 2% in interest costs, said an IIFCL official.

“This is a trial so we want to play it safe,” the IIFCL official says. “We’re not going below ‘BBB’ because we are guaranteeing half the debt, and a lower credit rating will require us to sponsor more than that.”

If IIFCL’s programme succeeds, the government should consider expanding the facility to companies with lower credits and assist in making businesses more viable. Adjusting guarantee fees is another way to allow more companies to tap it, as bankers suspect that those charges may be too high.

“Today a bank loan is available at 12%, while one would pay 10.5% from issuing a rupee bond. If I have to pay more than the difference [between the two rates in] guarantee fees then it doesn’t make sense,” says a Mumbai-based debt banker. “A bond is a fixed instrument and a loan is floating, so if we expect interest rates to come down I would rather borrow in the floating product.”

He believes that IIFCL, which is 100%-owned by the finance ministry, is charging a 250 basis point (bp) guarantee fee, but argues that a 25bp-50bp range would make more sense.

Infrastructure companies can also take bond funding by refinancing maturing loans. This would be a sensible compromise, as companies could extract loan funding as needed in the initial stages. They would be better placed to issue bonds by the time the loan matures because the project should be well under way and demonstrate viability. This would also free up banks’ capital to invest in other loans.

“First we need to have instances of refinancing happening through the bond market. And thereafter we should go to the next step of initially going to the bond market from the entry stage itself,” says Kotak’s Kashyap.

Tapping foreign investors

One way to support this bond issuance would be to entice foreign investors, who would be willing to accept local bonds provided they can quantify their risk exposure.

Yet restrictions on India’s bond market make it difficult and costly for foreigners to invest into local bonds. Any investment by foreign institutional investors into Indian local and foreign-currency bonds is subject to a 20% withholding tax applied on the coupon date. Additionally, the central bank caps foreign investor limits on bond purchases at US$60 billion. A quarter of purchased government bonds must be invested in maturities of at least three years.

“We would highly recommend that they amend the existing withholding tax… It’s low for loans versus bonds and securities, which doesn’t make sense,” says a head of DCM banker.

Foreign investors would also be more willing to buy local infrastructure bonds were India to introduce long-term currency hedging products. While India’s bond yields are higher than those of Indonesia and the Philippines, further rupee weakening would erode this cost advantage.

“One of the deterrents for foreign fixed income investors is the absence of these products,” says Fitch’s Nandakumar. “This is part of the reason why they would not want to invest in Indian infrastructure projects because just looking at the volatility of the currency and the consequent uncertainty, whatever returns they earn might get simply wiped out if they are unable to buy protection on the currency.”

Encouraging development of these derivatives would promote more foreign participation in India’s bond market in general.

Foreign investment would also support new bond issuance by the restructured SEBs. Indonesia succeeded in a similar deal, when its near-bankrupt national utility Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN) issued US$1 billion in 10-year notes last November, and it is planning another issue in the fourth quarter. Such bond issues would also bring more scrutiny, helping ensure companies do not fall into such parlous financial states again.

“PLN’s financials at that point of time may not have been the strongest but the ratings agencies took a view that it is too important for the country – it’s the national grid. And those deals got done,” says a DCM banker.

It might be worth buying the bonds of an SEB with sustainable debt levels that can pass increased costs to customers, particularly if it has an implicit or explicit government guarantee.

Need for reform

With few signs that the global downturn will ease soon, India’s banks look likely to cut infrastructure funding as the borrowing needs of power companies grow. Add the fact that a ratings downgrade to junk is imminent in India, and the cost of international funding for banks and corporates looks set to rise.

India’s politicians like to talk about infrastructure investment plans, but their willingness to act has been lamentable and their desire to keep power costs low for potential voters is short-sighted. There’s little point in cheap power if the cost is industry-wide insolvency.

If India truly wants private companies and investors to spend billions on building its infrastructure, it must cut red tape.

Allowing its companies to run profitable businesses is no sin, even if households must pay a little more. Lifting taxes that cripple international investors in the local bond market, and developing currency swaps to support their interest, should be seen as progressive, not regressive.

New Delhi must enact these measures, and fast. Otherwise it may well be revealed as powerless in more than one sense.