Taiwan has taken a series of once-unthinkable steps towards rapprochement with China since the Kuomintang party gained power in 2008.

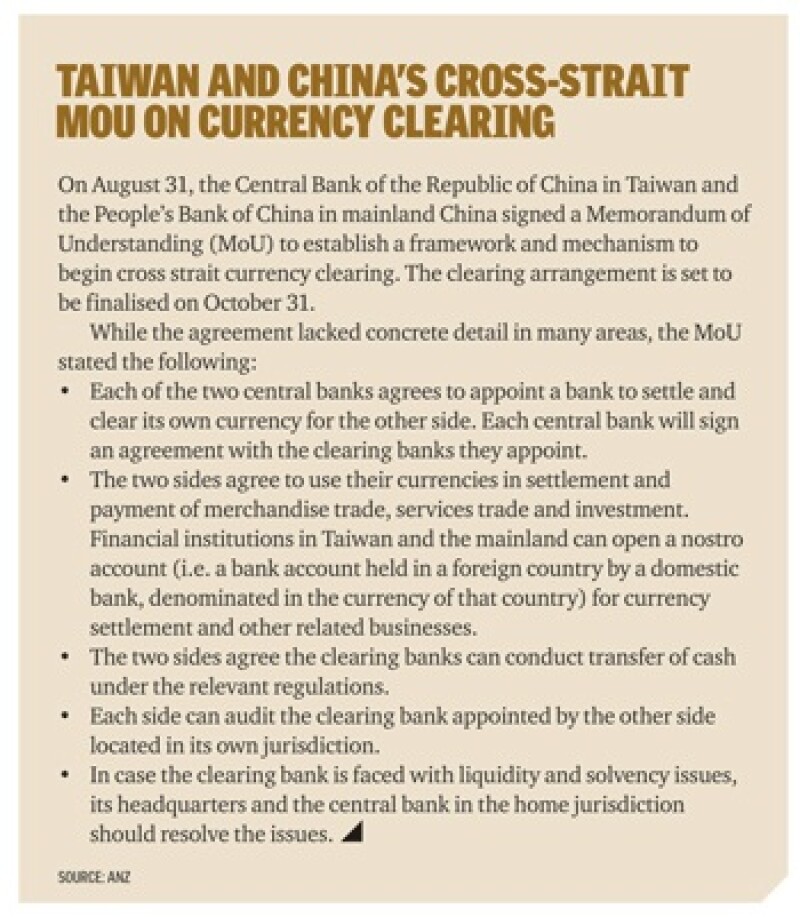

On August 31, it added another – the signing of the cross-Taiwan Strait currency settlement mechanism memorandum of understanding (MoU).

The agreement will let Taiwanese domestic banks offer clients renminbi-denominated accounts through which they can conduct mainland business and serve mainland visitors to Taiwan. The MoU is scheduled to take effect 60 days after signing.

It offers Taiwan potentially big ramifications. “Given the extent of trade linkages between Taiwanese corporates and the Chinese market, the potential demand for [renminbi-denominated] facilities is h uge,” says Leong Wai-ho, senior regional economist at Barclays Capital.

Over the past 20 years, Taiwanese businesses have invested more than US$200 billion in capital stock in China, largely via banks in Hong Kong. Today, 1.1 million Taiwanese live and work in China – in Fujian, Jiangsu and Guangdong, says Leong.

“Add to that 558 flights crossing the straits each week – bringing an estimated three million Chinese tourists and investors to Taiwan each year. The potential here could top Hong Kong.”

The island’s ability to declare itself the latest international hub for renminbi settlement was not widely expected, making the announcement all the more positive.

“Taiwan has turned out to be the black horse that has ‘won’ the race to be the first destination of expansion of the offshore renminbi market beyond Hong Kong,” noted J.P.Morgan’s Daniel Hui and Ying K. Gu in a research note. “Earlier speculation had favoured first Singapore, and then London, as potential second offshore RMB centres.”

The hope for Taiwan is that its ability to offer renminbi services helps draw much of the banking demand of its own corporates back to local banks, while international companies and investors become attracted by the pool of capital denominated in the currency that it looks set to create.

For China, allowing Taiwanese companies to use renminbi offshore helps to disseminate its currency internationally, adding to its respectability and importance.

Renminbi settlements now account for only 3% of cross-strait trade, which hit US$120 billion last year. The cross-strait currency clearing regime with Taiwan could see this rise to 10%, or US$12 billion a year, major business potential for domestic financial institutions.

Add in the ability of Taiwanese banks to fully service local companies working in China, and the MoU could have a big impact on the country’s financial sector and broader economy.

Two years of trying

Taiwan has pushed for two years to get direct renminbi clearing and settlement with the mainland. Before that, Taiwanese individuals and companies couldn’t access renminbi at home.

The Central Bank of the Republic of China (CBC), Taiwan’s central bank, started allowing domestic banking units (DBUs) to convert renminbi into cash in 2012, but solely for foreign tourists.

The new rules will allow DBUs to offer renminbi accounts for residents and conduct a full range trade settlement and transaction services. This had previously been limited to offshore banking units (OBUs) which were granted permission to conduct offshore renminbi business in September 2011.

As of April 30, 2012, there were 62 OBUs with assets of US$157.91 billion, of which 80% is held by domestic Taiwanese banks, according to the CBC. These accounts are heavily related to trade, conducting US$31.5 billion of export-related business and US$27.16 billion of import-related business in April.

Given that China is Taiwan’s largest trading partner, much of this would have been related to deals between the two countries. But Taiwanese exporters earning Chinese renminbi have to convert them first into US dollars before exchanging them into New Taiwan dollars.

Under the MoU, exporters can directly exchange Chinese renminbi into New Taiwan dollars. That may save them almost NTD50 billion (US$1.67 billion) a year in foreign-exchange losses and fee expenses for local enterprises, according to a recent statement by Chang Pen-tsao, chairman of Taiwan’s General Chamber of Commerce.

The new arrangement will also make it easier for Taiwanese banks to service local companies operating in China.

“The main needs of Taiwanese businesses in China are remittances, trade finance, working capital and syndicated loans,” says Leong. “Now for the first time, Taiwanese banks can directly open branches close to their clients in China and offer clients these facilities.

“Even small- and medium-sized Taiwanese companies doing business in China can now access these facilities for a reasonable fee, instead of relying on banks in Hong Kong.”

The opening of the renminbi market should also bolster Taiwan’s wealth management business. A report by HSBC Taiwan reported that 40% of affluent Taiwanese would like to open renminbi banking accounts.

Dearth of details

While Taiwan’s banks are excited by the MoU’s prospects, the announcement’s lack of detail has left questions.

Under the MoU, Taiwan will select a Chinese bank as a settlement bank for New Taiwan dollar transactions, while China selected Bank of Taiwan as a settlement bank for Chinese renminbi transactions. Each side’s selection must be approved by the other.

Some observers wonder why both these clearing banks were not immediately identified in the announcement.

“Maybe there are still technical issues to resolve,” says Raymond Yeung, senior economist at ANZ Research. “They could have [named] the clearing banks, but they did not… The pace of development is not as fast as we would have expected.”

The delay in identifying the settlement banks could be because China and Taiwan will implement a dual-track system, different from Hong Kong’s single-track offshore trade settlement.

CBC governor Perng Fai-nan has been quoted as saying that the cross-strait model “will be absolutely different” from that adopted in Hong Kong.

In a dual-track system, the mainland’s Bank of China would be the main clearing bank through its Taipei branch, serving a function similar to its branch in Hong Kong. But financial institutions in Taiwan would also be able to choose Chinese counterparts to handle transaction settlements. In other words, the new system would open multiple channels for currency settlement.

In Hong Kong, by contrast, the Bank of China (Hong Kong) alone settles renminbi transactions, according to a quota set by Beijing. That gives the mainland government a lot of control over liquidity of its currency in Hong Kong (although the city’s central bank also has a renminbi liquidity facility through its swap agreement with the People’s Bank of China).

Hong Kong bankers are said to be frustrated by the inconsistent practices of Bank of China’s Hong Kong branch, which allows some fund transfers to the mainland but rejects others.

If Taiwan’s system can demonstrate greater flexibility and predictability it could begin to draw funds seeking conversion into renminbi from Hong Kong.

Several Taiwanese banks’ overseas branches or OBUs have already set up renminbi settlement accounts at banks in China. Taipei Fubon Bank, for example, maintains one with its mainland partner, Xiamen Bank, in Fujian. Bank SinoPac has the same arrangement with the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China.

Seven banks from Taiwan now have mainland branches, and four more have representative offices.

Taiwan vs. Hong Kong?

Initially at least, the advent of Taiwan’s clearing system is unlikely to lead to two distinct versions of the offshore renminbi.

“CNH [Hong Kong-based offshore renminbi] and CNT [Taiwan-based offshore renminbi] will be theoretically the same exchange rate, since offshore renminbi funds are already fungible between Hong Kong and the rest of the world (including Taiwan),” noted the J.P.Morgan research note.

“There may be some CNH-CNT basis [difference] due to market inefficiencies, but it will be much more marginal compared to the CNY-CNH spread operates. Therefore, there will unlikely be many trading opportunities in CNH-CNT spreads, in the way that some investors and corporates traded CNY-CNH spreads in the past.”

However it could cause Taiwan to erode Hong Kong’s identity as the hub for offshore renminbi services and liquidity.

For a start, Taiwan is likely to eventually develop a large pool of renminbi due to its trade account surplus with the mainland. In 2011 the island enjoyed a trade surplus of US$89.8 billion with China, while Hong Kong had a trade deficit of US$252.5 billion. Taiwan’s current renminbi deposit level stands at Rmb15 billion.

While China’s overall imports fell in the first half of 2012, its imports of Taiwanese items on the “early harvest” list under a 2010 Cross-Strait Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA) increased by 104% year on year.

Taiwan’s increasing levels of renminbi liquidity will come in part at Hong Kong’s expense, as Taiwanese banks operating in the city to access renminbi return home.

“We expect Taiwanese banks to shift renminbi business from Hong Kong to Taiwan,” says Dariusz Kowalczyk, senior economist and strategist (fixed income markets research) at Crédit Agricole CIB, for Asia ex Japan. “Currently the amounts are relatively small, but are likely to grow pretty fast now that it’ll be much easier to conduct the business using clearing at home and renminbi liquidity from the currency swap.”

That shift of renminbi liquidity back to Taipei is likely to provide the catalyst for new renminbi services.

“We expect that a CNT market will develop, across asset classes – FX, interest rates, credit, and their derivatives,” says Kowalczyk. “The regulatory environment may well make it a more closed market than the global one in Hong Kong. Bond issuance to raise funds will be its major part, but it depends on regulations whether only Taiwanese businesses can raise funds or mainland ones as well. I suspect the latter will be the case.”

Adds Leong: “The next stage is for PBoC [People’s Bank of China, the mainland’s central bank] and CBC to hold each other’s currencies in their foreign-exchange reserves.”

However not everyone believes the rise of Taiwan’s renminbi business will cause an immediate decline in Hong Kong’s.

“The first issue is to build up liquidity to finance the renminbi pool,” says ANZ’s Yeung. “In Hong Kong there is a large amount of deposits, because of Hong Kong’s good timing. But in Taiwan I don’t see that pace of development happening. The renminbi has been appreciating from Rmb7 to the dollar to Rmb6.3, but now this appreciation has slowed down [lessening the incentive for locals to convert currency into renminbi]. So it will take more time for the renminbi to develop a pool in Taiwan.”

He adds that Hong Kong’s more established infrastructure for bond-raising and fund-raising will be hard to beat.

“Is there a Taiwanese financial community familiar with this type of issuance? For issuers, can they earn a better spread? Is there a good infrastructure? Taiwan will need to push to achieve this.”

However, if Taiwan can shift even a fraction of its financial market activity into renminbi, it can create a sizeable market. A BBVA April research report notes that Taiwan’s financial assets amounted to 367% of gross domestic product (GDP) at the end of 2011; it has a larger bond market than in Hong Kong or Singapore; and its total stock-market capitalisation was US$635 billion at the end of last year, just US$100 million lower than Singapore.

The outcome

Taiwan’s renminbi abilities in services and settlement mean its businesses and banks will be able to offer a broader array of services.

That’s good news for Taiwan’s economy, where GDP relies on volatility-prone technology exports.

“The real meaning [of the MOU] is to transform and upgrade the Taiwanese economy to become a more services-oriented economy, rather than just a backyard for entrepreneurs to keep their families in,” says ANZ’s Yeung. “The integration should mean that Taiwan will get more investment from China. In the long term, what this [agreement] means is a structural shift in Taiwan’s economy.”

In 2011, Taiwan agreed for the first time to allow Chinese investors to take stakes of up to 10% in Taiwanese technology companies, and up to 50% in new technology-sector joint ventures. For Taiwanese companies, the new rules will make it easier to forge strategic alliances with customers or suppliers in China, already by far Taiwan’s biggest export market.

Taiwanese manufacturers make nine out of 10 notebook computers in the world, but they have been under margin pressure.

Their ability to more easily make such alliances looks likely to attract other companies too.

“There will be interest from Japanese companies to form strategic alliances with Taiwanese firms to venture into China,” predicts Barclays’ Leong. “Taiwanese firms lack the branding that Japanese firms can provide, and Japanese firms can tap into the contact base and the cultural advantage that their partners would have. So the CNT market and the IPA [Bilateral Protection and Promotion Agreement] along with ECFA can enhance the appeal of Taiwan as a gateway to China.”

The sort of companies that might benefit are Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, the world’s biggest contract chipmaker; Hon Hai Precision Industry, the Taiwan-listed parent of Foxconn, which is the world’s largest electronics manufacturing services provider; and AU Optronics, the world’s third-biggest flat-panel maker, which recently received approval from Taipei to set up its first plant in China.

“The MoU is designed as part of a powerful bundle,” says Leong. “It is aimed not just at attracting Chinese investors to Taiwan, but also at getting other investors to explore China… the excitement is strategic, it goes beyond Taiwanese banks.

“Both economies will become more closely integrated as a result.”

Hong Kong may not be welcoming another renminbi hub so close by, but for Taiwanese companies with mainland links the MoU is good news. They, and the island’s economy in general, could reap sizeable rewards.