Thailand has embarked on one of its most important challenges since the 1997 Asian financial crisis: a revamp of its financial markets. It is determined to become one of Southeast Asia’s most developed bond markets to fund an overwhelming amount of infrastructure needed for sustainable growth.

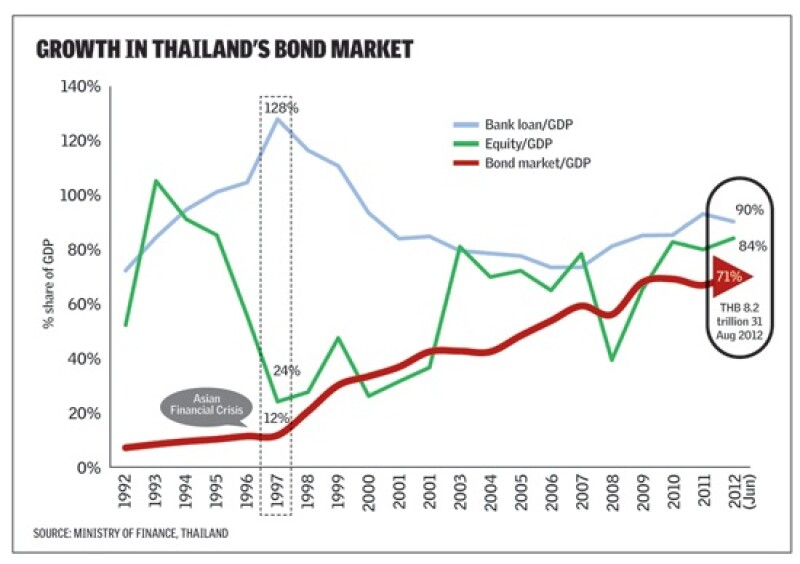

The country’s bond market is still growing, and of late the pace of improvement has been remarkable. It launched its first US-dollar benchmark bond issue only in June 1998 to raise finances for a financial system ravaged by the Asian crisis. In the years since, successive governments have greatly improved the country’s fiscal situation, partly through expanding its local bond market.

Thailand’s domestic bond volume (of which government and central bank bonds comprise 73%) skyrocketed from 12% of gross domestic product in 1997 to 71% as of the end of August this year. The government is expanding this market too; it is the only country to have issued a 50-year bond deal aside from the UK, France and China.

It’s just as well it has been willing to grow this market. Because a combination of insufficient spending on infrastructure and severe flooding in late 2011 has left the country needing to invest staggering amounts to improve logistics.

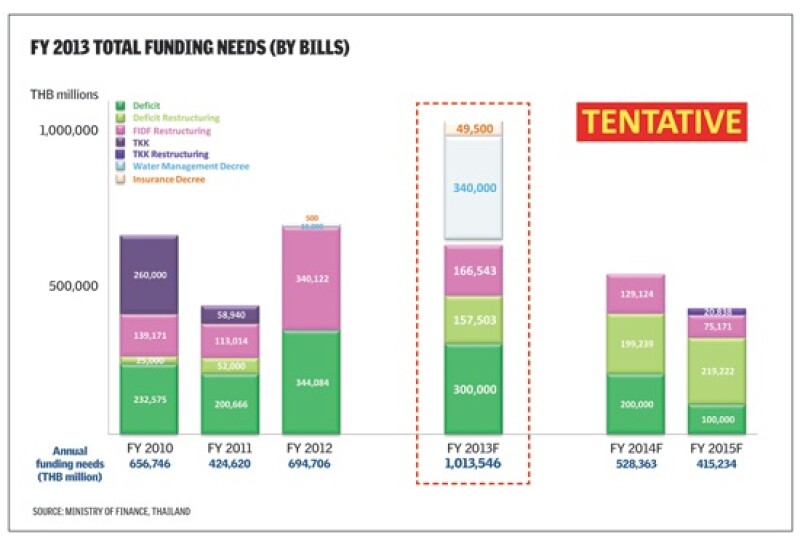

The country needs to find an estimated THB340 billion (US$11 billion) to build dams and drainage systems under the Water Decree to keep its largest foreign investors onshore, after the worst floods in 70 years halted production at Nissan, Hitachi and Toshiba and prompted Pioneer to consider moving its Thai operations to neighbouring countries.

It also requires US$72 billion for highways projects promised as part of The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) plans to connect Thailand with neighbours such as Myanmar and Vietnam. These are large sums that the Thai government simply doesn’t have.

So Bangkok is turning to its growing bond market. The government intends to expand the THB8.2 trillion bond market by as much as 20% a year for the next five years, effectively increasing outstanding bond volumes to up to THB20.4 trillion by 2017, according to Thailand’s Public Debt Management Office (PDMO).

It’s an ambitious goal. To reach it, the PDMO says it will launch its first amortised bond issue in December and introduce a 15-year inflation-linked transaction to extend its existing 10-year inflation-linked bond yield curve. It is also in discussions with investors to sell a US dollar-denominated bond for the first time since 2006.

“I am proud to say that we have achieved multiple tasks of meeting funding requirements, deepening bond market development as well as enhancing the government debt portfolio,” PDMO director general Chularat Suteethorn tells Asiamoney. “Now, our mission is to develop the domestic bond market to the international standard. I am quite certain that the Thai bond market will take a leading role among Asean countries.”

But problems still exist. The most worrisome is the lack of trading volume in any bonds longer than 10-year deals, courtesy of a thin local investor base comprised mostly of buy-and-hold life insurance companies, and mutual and pension funds. Thin volume is preventing more foreign investors from allocating.

To its credit, the PDMO is trying to issue more bonds and nudge primary dealers to trade more actively by adjusting trading restrictions. But Bangkok needs to dig deeper if it is to attract new investors in the numbers needed to match its ambitious funding plans.

Boosting liquidity

Given that it will take years to build the roads and flooding protection that Bangkok has identified, raising long-term debt to finance these projects makes the most sense.

“Like any country in the region, Thailand has to look at how it is rated, its borrowing needs and the costs of its various sources of funding, taking into account different tenors and maturities,” says Arjun Goswami, director of the Asian Development Bank’s Regional Cooperation and Operations Coordination Division. “It is fair to say that a diversified pool of resources would be more sustainable to support long-term infrastructure development.”

The PDMO has certainly been keen to expand the size of existing government bonds and extend its yield curve.

To do this it intends to continue issuing bonds in existing tenors. This will show that it will supply benchmark bonds regardless of budget uncertainty by raising auction sizes in three-, five-, seven- and 10-year bonds up to THB20 billion by September 2013 from THB4 billion in 2007. It also plans to raise turnover ratios in the longer tenors of 15 years and over, according to the PDMO’s Chularat. The turnover ratio in the five-year bond currently stands at four times.

There’s a clear reason to expand these existing bonds; it offers comfort to foreign investors.

“[Daily bond] traders are mostly foreign investors; if they don’t trust the Thailand benchmark, they won’t go for the 15-year or 20-year [bond]. If it doesn’t have a high turnover ratio, it will be difficult to go in and come out. So if they doubt the Thai [economic] prospects, then they probably won’t want to stay that long. That is why for the longer tenor you want to reopen them at as large a size as possible,” says Chularat.

The PDMO’s efforts to date are already yielding results. A focus on issuing generally longer-dated bonds has extended the government’s average debt maturity from five years in 2007 to nine years so far this year.

The agency’s efforts to create a deeper bond market have also made Thailand a regional trailblazer. The government issued Southeast Asia’s first inflation-linked bonds in July. It plans to follow that by raising THB40 billion in 15-year inflation-linked bonds by September 2013, and reopen the 10-year inflation-linked bond after the existing tenors mature in seven years to lure investors into the longer-dated side of the yield curve.

The PDMO’s sensible steps to expand liquidity in government bonds are gaining approval. International fund managers now hold 11% of Thailand’s outstanding bonds, from almost zero in 2007.

“[Rising investor] demand for emerging-market debt has definitely helped [Thailand],” says Pongtharin Sapayanon, head of fixed-income research for Aberdeen Asset Management in Bangkok. “The way the government has built up the Thai bond market by issuing benchmark bonds in big sizes has helped [as it] provides liquidity. It offers the bonds at a lot tighter than before.”

Yet for all this development, Thailand’s bond market is still well behind many of its neighbours.

“Liquidity in the Thai bond market, especially in government bonds, is probably not as [much] as other markets like Indonesia and Malaysia,” says Vasu Suthiphongchai, fixed income director for Manulife Asset Management in Bangkok.

Fake volume

Aside from gradually boosting bond volumes, the government is looking at other ways to offer the liquidity that foreign investors want.

On August 28, Thailand’s Ministry of Finance announced a new set of primary dealer rules, official on October 1, increasing the number of primary bond dealers in Thailand from eight to 13. The list includes Bangkok Bank, BNP Paribas, Citibank N.A., Deutsche Bank, HSBC, JPMorgan Chase Bank, Kasikornbank, KGI Securities, Krung Thai Bank, RBS, Siam Commercial Bank, Standard Chartered Bank and TMB Bank.

Each primary dealer must take up a 5% allocation of their total aggregate holdings in government bond auctions in maturities of three, five, seven and 10 years.

Primary dealers also have to offer secondary-market trading equal to 5% of the outstanding volume over a 12-month period, so the minimum participation in auctions and the secondary market rises from 3%.

The government first announced its intention to appoint more primary dealers in January. Since then, banks and securities houses have bolstered ownership of government bonds to impress the authorities and gain a licence. That has led quarterly bond trading volumes 25% higher than usual, but the trading has been artificial.

Bond trading volume has actually dropped since the additional PD licences were issued after the trial period ended in June. Inter-dealer and dealer-to-client trading values hit their lowest year-to-date levels in September at THB556 billion and THB1.02 trillion respectively, according to the Thai Bond Market Association.

“Some banks bought at a specific rate and five minutes later, they would sell at the same rate just to increase the volume,” says a Bangkok-based trader. “There is fake volume in the market, although the real volume has definitely come up.”

This has frustrated some primary dealers who say they are trying to meet PDMO requirements since inflated volumes dwarf genuine efforts.

“Some banks are throwing volume around a bit. Whatever incremental improvement I try to make is overshadowed by the fake volume,” says Thiti Tantikulanan, head of the capital markets business division of Bangkok-based Kasikornbank.

Real volume is estimated to be about US$300 million a day, but that has been inflated to about US$1 billion, according to market sources. The distortion undermines the effectiveness of the PD rules since dealers are able to find ways to manipulate the loopholes. It will also hamper the PDMO’s future efforts to boost trading liquidity due to inaccurate volume figures.

One way to solve the problem would be for the PDMO and Thai Bond Market Association to regularly inspect trader records to ensure that they have not been selling and buying back bonds to a single counterparty – and apply punitive measures accordingly.

“[Fake trading] should be fairly easy to spot because it would be done within a day,” says Thiti.

Buy-and-hold blockage

Aberdeen’s Pongtharin agrees that the existing PD rules will not be enough to stimulate secondary-trading volume.

“[Primary dealer rules] may improve at the margins but I don’t think that’s going to be a driver of increased liquidity going forward,” says the researcher.

What is most needed is for investors that already participate in the government bond market to trade in greater volumes and more often. Asset management companies are the biggest pool of bond-market participants, comprising 52.6% or THB537.4 billion of total trade volume in September. The trouble is that many of them, particularly insurance companies, like to buy bonds and then hold them to maturity, stifling liquidity.

One way to promote liquidity would be to make it unappealing for insurance companies to buy and hold in such a manner. An easy way to do that would be to make them report the value and return of bond investments at their market valuation rather than purchase price – known as marking to market.

The value of marked-to-market investments is far more volatile than those kept at initial valuations, which can cause shifts in a company’s financial statements. That disincentivises them to sit on major investments for a long time. Currently Thailand’s Office of Insurance Commission, which is directly linked to the finance ministry, only requires equities to be marked to market.

“Life insurance companies, in terms of their investment portfolios, do not have to mark to market [bond investments]. So they buy at 4%, they hold at 4% and in their accounting it’s at 4%,” says Pongtharin. “[If you add marked-to-market regulations] there will be more buying and selling, they will need to look at what’s in their portfolio, what’s expensive, what’s cheap and more portfolio management on the insurance side. But right now, there’s just no need for them to do so. They buy it up in the primary, secondary, and they hold. And that’s just about it.”

Repo market

The government could also promote liquidity by revamping its repo market to encourage more two-way trading in an environment where most investors buy and hold.

A repo market allows the borrower to access cash in exchange for collateral in the form of a Thailand government bond. Repos effectively allow institutions to borrow more as long as they are able to offer collateral. In turn, the lender can also choose to short the collateral in the market with the hope that they’ll be able to make a profit instead of merely holding on to the bond.

Vibrant two-way trade not only increases liquidity, it also helps temper volatility since those shorting bonds will pace market movements when an event prompts bond yields to rise or fall excessively. But Thailand is far behind in this because of structural obstacles and costs.

Cost is a large deterrent. Using the repo market will require participants to pay a 46 basis-point charge levied by the Financial Institutions Development Fund (FIDF), which supplies funds to the country’s lenders in times of stress and is overseen by the central bank.

“The repo return after one pays the FIDF fee now is much lower than investing directly in a bond or short-term bank deposit,” says the PDMO’s director general, without offering a solution.

Commercial lenders say there is another reason why they seldom visit the repo market. In a bilateral repo transaction with the Bank of Thailand, a commercial bank would lend the central bank cash and receive collateral in return. However, the central bank does not specify which type of collateral it will give commercial lenders. When the commercial bank receives the bonds, it is forced to shop around among other institutions until it finds someone willing to buy that bond. It’s time-consuming and inefficient to short collateral in Thailand.

What bond will I get?

“The Bank of Thailand will throw us whichever bonds they have in their portfolio. This way it makes it very hard for me to short any bonds because I’m not too sure at the end of the day when I place my money, what bond I’m going to get,” says the senior trader.

This is not the case in Singapore, for example, where a lender receives the bond it wants. The Bank of Thailand cannot do the same because it has a limited number of bonds in its portfolio, and is not mandated to issue bonds for this purpose.

This obstacle means banks are dissuaded from accepting bonds used in collateral for repos, which stymies liquidity.

Market participants say the answer is simple; the government should let them choose the bonds they want.

“The focus of the market has to be geared more towards shorting,” says another trader at an offshore bank. “If we are allowed to choose the bonds, then we have a lot of inventory where we can repo around. That will create liquidity. At the end of the day, the repo is like a building block in a bond market.”

A partial solution would be for the Bank of Thailand to list the bonds available in the repo market as collateral months in advance. This would at least give banks time to plan their repo activities.

The central bank could also accept specific bond requests from commercial banks. However, such a system would require an electronic application process to ensure transparency.

Implementing each of these suggestions could potentially create a virtuous circle, adding to secondary-market liquidity, and in turn encouraging foreign investors to allocate more resources and help spur bond-market growth.

Maintaining momentum

There is little doubt that Thailand’s authorities are improving the bond market, but it is important not to lose momentum at a time when more investors are becoming optimistic about the country’s growth prospects.

The government’s commitment to issue benchmark bonds on a regular basis to improve liquidity is an excellent start, but it’s just half of what’s needed for sustainable market development. Financial regulators must also focus on more ways to get investors to trade actively. Giving them the shorting instruments they need to freely buy and sell debt securities would be a good start.

Marking bonds to market and developing the repo market would encourage investors to buy and sell bonds more regularly and more easily. That would in turn encourage them to invest more into longer tenors, which is exactly what Bangkok needs as it embarks on an ambitious round of infrastructure spending.

Thailand’s infrastructure spending spree

Is Thailand’s storied infrastructure programme about to become a reality?

At a recent roadshow in New York, prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra told investors that her government is committed to pursuing infrastructure and water management projects with a total value of more than US$72 billion.

The ‘wish list’ of megaprojects to be built over seven years is long. It contains water resource management projects designed to stall a repeat of last year’s devastating floods, plus everything from high-speed rail and mass transportation systems to renewable energy projects.

Government officials claim that the projects will help lower logistical costs for raw materials and goods that make Thailand uncompetitive with other countries in the region. They claim the savings could boost gross domestic product (GDP) by as much as 0.8% a year.

Investors on the ground are less effusive.

“With the exception of the renewable energy projects, we haven’t seen any real details,” says Kanoklada Rerkasem, director and Thailand country head of CapAsia, a private equity firm that invests in regional infrastructure projects. “As things stand, there are many moving parts. Private equity houses like ourselves require a regulatory framework that facilitates investments and creates a reasonable degree of predictability and certainty.”

It’s early days, but plans for many of the government’s ‘mega projects’ are sketchy at best, and its ability to construct them on time with accurate budgets is far from certain.

The fear is that so-called seven-year projects will take considerably longer, as did the much-delayed Bangkok Mass Transit System (known as the Skytrain) or the corruption-plagued Suvarnabhumi International Airport.

“There is a genuine reason to improve Thailand’s infrastructure as competition from neighbouring countries, especially Myanmar, increases,” says Anthony Muh, executive director and chief executive asset management at H.R.L. Morrison & Co, a specialist investment management firm. “But the government is talking about a very large number of projects over the next seven years. Realistically they are going to have to prioritise.”

The good news is that funding isn’t a major issue. As of July, public debt stood at 42.5% of GDP, well below the mandatory ceiling of 60%, while the government’s foreign debt is almost negligible. The country has a lot of breathing space to expand bond issuance [see main story].

It can tap the country’s savings pool in other ways. One is through infrastructure funds listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET).

In July, Kasikornbank announced its intention to launch a THB5 billion solar-power infrastructure fund. The pilot fund will invest in up to seven commercial solar-farm projects run by Solar Power, a subsidiary of Thailand’s biggest solar-farm developer.

Maybank Kim Eng Securities (Thailand) also intends to launch infrastructure funds targeting investors seeking relatively stable returns and low risk.

“We expect the first infrastructure fund to be listed on the SET in the first quarter of 2013,” says Paveena Sriphothong, the exchange’s group head of issuing and listing.

Yet educating investors will take time. Kanoklada at CapAsia urges retail investors to conduct thorough research and to fully understand infrastructure funds before investing in them.

“They are far more complex than property funds,” she says, adding that if the first infrastructure funds are successful, more will follow.

PPP possibility

Another way to entice private-sector investors is through public-private sector partnership (PPP). The government is drafting a law to facilitate the sort of PPPs that could kick-start its infrastructure programme.

“One of the beauties of the public-private partnership model is that it can take account of the risks that the private investor faces so that they are best managed or mitigated, possibly through guarantees and assurances on time-frames,” says Arjun Goswami, director of the Asian Development Bank’s Regional Cooperation and Operations Coordination Division. “This would improve projects’ execution and increase private investor confidence.”

Not everyone is convinced that PPP will answer Thailand’s funding needs. Some investors complain of political interference in the setting of tariffs. Others say there is a lack of commitment.

“Officials at the Ministry of Transport or the Expressway and Rapid Transit Authority of Thailand simply don’t understand PPP,” complains one investment manager. “The problem is that the quality of the people is not great.”

A different option favoured by bankers is for the government to privatise existing state enterprise assets and use the proceeds to build greenfield projects. Or it could sell foreign investors a 50% stake in a brownfield project and co-invest.

The challenge will be offering private investors sufficient returns to risk their capital.

“As a dedicated long-term infrastructure investor, we do see opportunities in Thailand,” says Muh. “But the rate of return has to recognise the level of risk. Like most long-term investors, we are constantly comparing the higher-growth greenfield opportunities that Asia has to offer against brownfield projects in developed markets. Right now the lower risk of brownfield projects wins the day.”

The biggest challenge for Thailand will be to convince a skeptical audience that it will be in a position to successfully launch US$72 billion of infrastructure projects over the next seven years.

“Have they thought this through?” asks one investment manager. “It does not appear that they have. Don’t forget that countries like Thailand will be competing for investment with distressed assets in Europe.”

In the case of Thailand, however, there may be an even bigger reason to push through these badly needed ‘mega projects’. After years of political chaos, the Yingluck government has achieved a measure of stability. Not only does the Pheu Thai Party command a large majority in parliament but if there were an election tomorrow, it would probably win, securing another four-year term in office.

“If ever there was a time to implement big infrastructure projects, this is it,” says Andrew Stotz, Bangkok-based strategist for Maybank Kim Eng Securities. “The government should be aggressively addressing the opportunity. If they miss it, then shame on them. The timing will never be this good again.”