Asia’s debt syndicate bankers, investors and credit analysts have a favourite adjective to describe the pace of this year’s high yield bond issuance: “crazy”.

A combination of central bank easing, abundant liquidity and the US’s ability to avert a fiscal cliff has created a perfect storm of demand for speculative bonds in Asia. The result: an explosion of high yield bonds that spilled into the market as soon as the region returned to business in the first week of 2013.

During January, non-Japan Asia G3 currency high yield bond issuance soared to a record US$11.7 billion, according to data provider Dealogic. That is nearly the same amount as the total speculative-grade bond volume issued bef ore the global financial crisis for the whole of 2007, Dealogic figures show.

About 52% of this was issued by 17 Chinese property companies, despite the fact that just 12 months ago they were struggling to raise funds. Investor demand is such that corporates that only recently would have been regarded as too risky to invest in have tapped the market. One is Hopson Development Holdings, the first ‘CCC’-rated Asian company to issue bonds in seven years.

Demand for non-investment grade, or “junk” bonds, has meant that banks cannot get new deals done quickly enough. Raymond Chia, deputy head of credit research for Asia at Schroders, recounts blazing through multiple new issuance prospectuses through a weekend in January in his Shanghai hotel room, in between meetings with Chinese bond issuers.

At Aberdeen Asset Management, bond analysts have been poring over reams of data about the companies wanting to raise debt.

“It’s ridiculous. You cannot do the right amount of research to be comfortable these days to actually lend these people money,” says Anthony Michael, head of fixed income at Aberdeen. “It’s a stampeding bull market.”

More is coming. Debt capital market (DCM) bankers say many other junk-rated borrowers are keen to raise relatively cheap bonds. Lowly rated sovereign nations such as Bangladesh and Papua New Guinea have also expressed interest in tapping the international bond markets.

The combination of a frenetic pace of issuance and the willingness of the market to delve ever deeper into the junk pile is a worrying mix. Many investors are so focused on returns in this low interest rate environment that they are ignoring the financial risks of low-rated borrowers and the danger of a shift in economic headwinds.

Risks of the latter are sizeable. Economic growth in the US is hardly robust, with the country reporting a 0.1% contraction in gross domestic product during the last quarter of 2012. Meanwhile Europe’s bond yields have also tightened on the back of renewed confidence about the European Union, but the continent remains in an economic quagmire and shows few signs of pulling itself out any time soon.

The largest immediate risk to the appeal of Asian credits though could be news from China. The country has of late revealed improving economic fundamentals, which has done much to spur the interest in its junk bonds. But it has to do more to demonstrate it is in a sustainable recovery, and the country’s marked increase in borrowing over the past four years could well have caused repayment pressures.

Any of these scenarios would put daggers of dread through the region’s bond investors, with risky assets becoming the first victims. Yet none are being fully accounted for.

The central bank put

Asia’s high yield bond market rally is the result of two things: low interest rates across much of the western world, and enormous amounts of free investor capital made available by central banks buying the government debt of their own countries.

In an attempt to boost their economies, the US Federal Reserve (Fed), European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) have cut their interest rates to record lows, while printing money and using it to buy government bonds in order to free up private investor money.

The Fed announced plans of further purchases worth US$1 trillion this year, while the BoJ has pledged open-ended asset buying from 2014. The ECB said in September it would spend as much money as needed to support debt-laden nations in exchange for economic reforms.

The theory is that investors who sell government debt to the central banks will put their money to work in other areas, stimulating the economy. But it’s an imperfect response, particularly in today’s globalised world.

Because the economic prospects in these countries are uncertain and local rates are low, investors have moved large sums of this cash into countries and instruments where they can get better returns.

“It’s ridiculous,” says a Hong Kong-based credit researcher. “All of these [high yield bond] yields and prices are being artificially depressed by what’s happening worldwide, which is central bank liquidity. Spreads are tighter not because we expect the global economy to grow at 6%, 7%, 8%, but just because we know that there is a central bank put in every part of the world that will support and infuse liquidity into the system.”

Part of this flow of cash has come from wealthy private investors, largely via private banks, which offer them leverage to invest.

Many of these investors are chasing absolute returns, and in the present atmosphere seem almost indifferent to risk. And as bond yields have tightened at the higher end of junk ratings, some private bank money has been willing to gain exposure to even weaker companies.

“There are some new issues that we wouldn’t touch,” says Aberdeen’s Michael. “There are some companies where we’ve done due diligence, where there are some concerns about their business model, and a number of them are Chinese companies. But the problem we have is that private banking investors are still waving into this market. They’re still … happy to buy stuff with 6.5% yields with four times leverage, three times leverage.”

This flood of money has driven asset prices upwards, irrespective of credit fundamentals. That is worrying Mohamed El-Erian, chief executive of Pimco, the Newport Beach, California-based investment company with US$2 trillion in assets under management. In a Financial Times commentary on January 7 he said that the combination of excess liquidity and the hunt for yield is divorcing valuations from fundamentals, especially for specific assets such as corporate high yield bonds, and he warned of greater volatility in portfolios.

Soaking up liquidity

Asia high yield bonds have been a key beneficiary of this flow of cash.

Chinese property-developer bonds, for example, yielded total returns of more than 40% last year, outperforming other Asian high yield sectors as the space saw sales recover and credit ease in the second quarter of 2012. These credits have attracted even more funds in recent months in the absence of a hard landing from China.

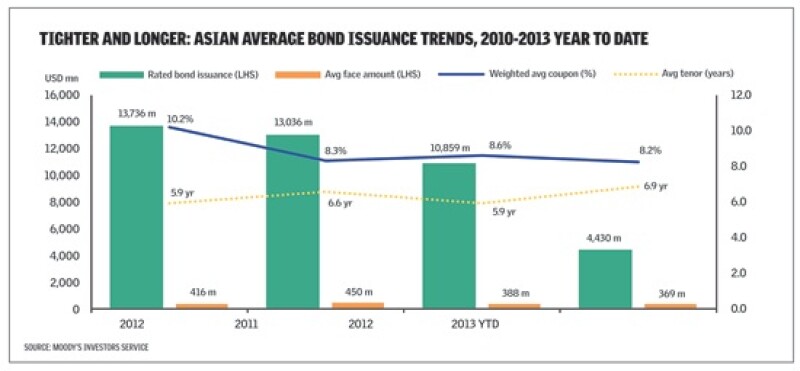

The performance of these bonds, and demand for them, is not wholly down to improved financial fundamentals. Moody’s said in a January 23 report that it expects year-on-year growth for Chinese property developers, following a 35.3% increase in October sales from the previous period in 2011. But liquidity continues to deteriorate for Chinese corporations, specifically for property developers, due to refinancing concerns.

Chinese property developers were also the culprits behind a spike in the Asian Liquidity Stress Index, which rose from 9.3% in 2011 to 28.6% at the end of last year, according to the rating agency’s report.

Yet Country Garden’s US$750 million issue maturing in 2023 was oversubscribed by 24.5 times, while Shimao Properties’ US$800 million 2020 bond issue was oversubscribed by 22 times. Both deals have an effective ‘BB-’ rating.

Investors raced for these bonds as Standard & Poor’s rated both deals a notch lower than the corporate credit ratings of the companies over concerns offshore bondholders would be materially disadvantaged compared with onshore creditors in the event of a default.

With liquidity having become the most important factor in the performance of many bonds, it’s difficult for investors to decide what to buy.

“You have to be cognisant that the things you are buying on an absolute basis have to be justified by the underlying fundamental analysis; that is, ‘are you really getting paid for the underlying risk?’ And I think in many cases you’re not actually getting paid for that risk,” according to Raja Mukherji, the Hong Kong-based head of credit research for Pimco.

China risk

Just one piece of bad news could cause much of the sentiment-fuelled investor cash that has flooded Asia’s high yield bond markets to evaporate. This could be a marked change to the economic outlooks of the US or Europe, for better or worse.

The biggest danger is bad news emanating from China where more than half of Asia’s high yield issuance is concentrated, in particular, the indebted companies and enterprises in China that may have to restructure their debt.

Local and regional governments in mainland China have amassed huge amounts of debt, resulting from the stimulus measures following the global financial crisis of 2008-2009. That figure stood at Rmb10.7 trillion (US$1.7 trillion), according to figures released by China’s National Audit Office last February, and news reports on January 29 say that local banks extended maturities on some of these loans, due at the end of last year.

While local and regional governments in China are banned from issuing bonds, they have set up special-purpose vehicles to raise the funding in their stead. Additionally, state-owned enterprises have relied on cheap funding from the country’s banks. The lenders have favoured these companies so heavily that private corporates have often had to rely on less formal means to raise debt, creating yet more market-risk concern (see box at the end of this article).

This is causing concern among bond analysts.

“Think of all the companies that are being supported artificially by liquidity channels either coming from the government or other sources. That’s where the problem sits,” says a senior credit analyst. “As long as China decides that they will not let the default situation implode and they will still find ways to support these companies, eventually they will have to restructure some of the debt.”

Broad swathes of debt restructuring could spur a bank-liquidity crisis within China. That would cause a spike in yields in most of the country’s bonds, but particularly those of the property developers who so badly need regular debt funding to grow.

“I think that will come back to haunt the market if they are not able to resolve some of the debt levels in the provincial and city governments,” says Arthur Lau, head of Asia ex Japan fixed income at PineBridge Investments.

This could easily be exacerbated by concerns over Chinese trust financing, while high levels of debt within the country’s local and regional governments remain. Now that more Chinese companies away from the property developers are trying to come to the international bond market to replicate their successes, an implosion of one or both of these risks will increase the number of companies in trouble.

Although China’s new political regime is unlikely to enforce extreme crackdowns on off-balance-sheet activities, or force a massive restructuring of local government debt in an attempt to exhibit their economic strength, lingering concerns over these issues could limit the ongoing appeal of Asia’s high yield bond market.

It’s not difficult to envisage a situation in which a major debt restructuring in China causes a sudden panic among bond investors and a rush to safety. That could well cause the Asian bond market to drop by as much as 20% and Asian junk bond yields to widen dramatically by 10%-20%.

Equities attraction

It doesn’t have to be bad news from China that spells the bursting of Asia’s high yield credit bubble. A continued improvement in the country’s economic trajectory could also mean the end of the allure to global investors.

Improving sentiment over economies tends to lead investors to be more confident about the future for companies. That, in turn, tends to drive rallies in equity markets.

Investors with a strengthening faith in the outlook for China and Asia in general are likely to decide that buying equities, which are only a little more risky than high yield or perpetual bonds yet offer unlimited upside, is a more sensible play.

Bank of America-Merrill Lynch (BoA-Merrill) forecasts a big shift of assets from increasingly low-yielding junk bonds to equities during 2013.

“While the industry flow data does not show ‘rotation’ out of bonds, our private-client data does. The structural long position in fixed income is simply threatened by low expected returns thanks to low rates and the mathematical reality that a small rise in rates can cause total return losses in portfolios,” said a January 24 report from the bank, written by Michael Hartnett, John Bilton, Kate Moore, Manish Kabra, Brian Leung and Swathi Putcha.

It wouldn’t take a major widening of bond benchmarks to cause losses. Negative returns on bonds globally would occur if the 30-year US Treasury yield rose from 3.03% to over 3.26% in the next 12 months.

Meanwhile, BoA-Merrill expects the S&P 500 equity index to reach new record highs and for Asian equity indices to gain as much as 15% over the year, while returns from both investment grade and high yield bonds are likely to be lower than equities.

This is a highly possible scenario as Asia’s once-dismal equity market is starting to show signs of bullishness. Equity capital market activity quadrupled in January 2013 from the US$3.6 billion the region raised in the same period last year. If this trend starts to become a surer occurrence, yield-chasing retail investors will not think twice about dumping their bond holdings.

Returns will be substantial in these equity markets, at least in the initial stages, as stocks will be rising from their low bases of 2012. A rapid exodus to equities from bonds will drive stock prices up quickly, and the sizeable returns would only fuel even more investors into equities and out of debt.

Gary Dugan, investment officer for Asia at Coutts Private Bank, believes that a shift out of bonds and into equities may already have started.

“We have seen increasing appetite for equities. Many investors have talked about selling their bonds and buying equities and we are finally seeing them put that strategy into action,” he says. “Issuers will be worried that a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to issue debt on exceptionally low yields may be coming to an end.”

Asia’s high yield credit market has enjoyed some very good times, largely due to the largesse of developed-market central banks. But the longer it takes for a meaningful correction to take place, the more time there will be for money to be spent on high yield bonds and for new low-rated deals to be executed irrespective of credit fundamentals (see box above).

“The longer we go on like this, the greater the likelihood that eventually there will be some pain,” says Richard Deutsch, global head of credit research at HSBC Global Asset Management.