Chinese companies have had enough of the chagrin of US investors.

Last month the formerly Nasdaq-listed Focus Media, one of China’s largest out-of-home digital advertising firms, attracted US$1.525 billion from global underwriters to help finance a US$3.7 billion privatisation by a consortium led by private equity firm Carlyle Group in December.

Focus Media’s desire to go private is hardly unique. In fact it is set to become the 47th US-listed Chinese company, or listco, to de-list over the past two years.

The steady flow of listco privatisations stems in part from lingering investor concerns about the companies, almost two years after equity short-seller Muddy Waters Research accused Chinese forestry company Sino-Forest of lying about its timber.

While Sino-Forest firmly rejected Muddy Waters’ specific allegations it was evidently in a precarious financial situation, because it filed for bankruptcy protection in nine months later, in March 2012. Other claims of fraudulent behaviour among Chinese listcos followed, impacting sentiment about many of these firms, and leading the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), the US securities regulator, to begin investigating some of the listcos and their auditors.

The SEC has deregistered the securities of nearly 50 Chinese companies and filed fraud cases involving more than 40 issuers and executives. In December it extended its hunt to global auditing agencies, deciding to investigate the Chinese branches of global auditing firms that do not submit documents on listcos.

The SEC’s investigations and demands have put Chinese companies and auditors in a tough spot, because under Chinese law local corporates are not allowed to supply some types of information to outside authorities. To avoid falling afoul of China’s regulators the listcos have therefore been reluctant to be overly forthcoming with information, but suspicious international observers have easily been able to construe this as a sign that the companies have something to hide.

The mixture of scandal, SEC investigations and the difficulty of listcos to meet US information disclosure demands has caused the valuations of many of these companies to plummet. Focus Media’s American depositary shares, for example, dropped from US$3.22 in August 2011 to US$20 by the end of January 2012, before rumours of its impending privatisation emerged. That in turn has led to the privatisations, and more are likely.

The current market speculation is that Nasdaq-listed web portal Sohu will be next. Sohu’s co-president and chief financial officer Yu Chuyuan says her company has no interest in privatising, but rumours persist that it has approached investment banks and private equity buyers after its stock plunged from more than US$100 a share in April 2011 to US$48 a share by the end of March 2013.

Dozens of other listcos have gone dark, effectively ending active participation in the stock market to avoid the fees necessary to stay listed, draining the confidence of investors and suitors in these shares.

All in all, it has led to a very poor image for China’s listcos in the US.

“Sentiment about Chinese US-listed businesses is very mixed,” says one private equity fund manager who has considered buying listed companies, to no avail. “Some people believe there are … hidden gems still listed, but I cannot see much value in a lot of the businesses remaining... Our team has done due diligence on a lot of companies, and every single one has been far worse than we imagine.”

The fund manager says that he investigated 10 over-the-counter Chinese companies listed in Hong Kong, Singapore, the Nasdaq and New York Stock Exchange in the past 18 months. Eight of them were listed via a reverse merger – a process by which a public shell company is acquired by a private company, thus allowing the private company to bypass the lengthy listing process.

Among each of the companies he researched, the fund manager found fault with the companies’ accounting, cash flows or investor relationship – or all three.

Two things need to change to alleviate the problems listcos face in the US. Firstly, aspiring Chinese listcos need to become as transparent as they can. Secondly, the regulators of the US and China need to better coordinate their disclosure requirements. Until both steps take place Chinese companies will continue to find it extremely hard to raise capital in the world’s largest economy.

Pain and little gain

Five years ago the US was still an attractive initial public offering (IPO) market for Chinese companies. They liked the country’s bourses because they didn’t demand years of a profitable track record, nor the regulatory hoop-jumping required by more obvious markets such as Hong Kong and China’s A-share market.

Technology-focused companies in particular were attracted to the Nasdaq, known for being the most sophisticated bourse for tech companies globally, home to names such as Amazon, Ebay, Facebook and Google. The opportunity to list – either via IPO or reverse merger – meant Chinese companies could capitalise on investor buzz instantaneously without reporting three-year profits.

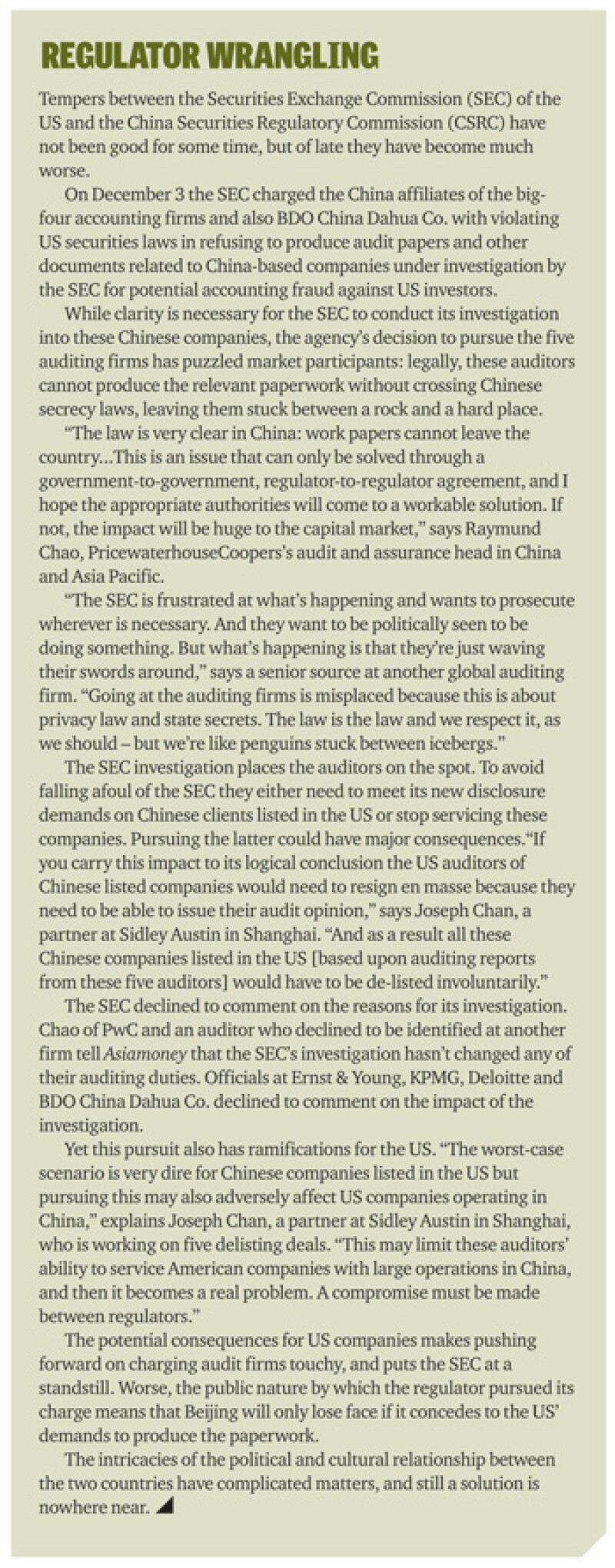

Initially, mainland Chinese companies listing in the US were hailed as smart plays on a booming economy. But as economic conditions have soured, so has the favour bestowed on these stocks. Their performance since the global financial crisis of 2008 in particular has been woeful.

Even top names such as Nasdaq-listed Sina, Renren and Youku Tudou have not done well. By March 15, Sina was trading at US$48.27 a share, versus the US$110-US$133 value its shares enjoyed two years ago. And Renren, touted as China’s Facebook, had slithered from a debut price of US$16.80 on May 6, 2011 to US$2.97 on March 15.

The valuations of many listcos have apparently plunged because of investor concerns about offshore-listed Chinese companies in general. This scepticism is in large part a result of the unwillingness of many Chinese companies to offer up much information about their operations. That in turn has been seized upon by some short-sellers, with highly public allegations of financial wrongdoing or discrepancies made against a few listcos.

The first major example was in June 2011, when Muddy Waters Research’s Carson Block accused Chinese forestry company Sino-Forest – which was Toronto-listed and backed by Carlyle and hedge fund Paulson & Co. – of misstating its forest holdings. The company’s capitalisation dwindled from about CAD6 billion (US$5.89 billion) to less than CAD1.2 billion by the time its shares were suspended in August 2011. It filed for bankruptcy protection on March 30, 2012.

While Muddy Waters’ accusations against Sino-Forest was the most famous example of a short seller targeting a listco, it was far from an isolated incident. In January 2011 Citron Research and Bronte Capital accused China MediaExpress of having conducted a reverse merger that was “too good to be true” after growing faster than any other US listed Chinese media company over the previous four years, despite spending a lot less than rivals on infrastructure. Citron also criticised Harbin Electric on August 22, 2011 for a lack of transparency. Earlier, in 2009, short seller John Bird and Manuel Asensio questioned details in China Sky One Medical’s financial reports and its frequent change in auditors.

Muddy Waters targeted other listcos too, accusing DuoYuan Global Water of overstating its revenue amongst more serious claims in April 2011, and claiming in June 2010 that Orient Paper misappropriated almost US$28 million that the company said was for a production line to make corrugating medium paperboard. Muddy Waters has written seven reports on Chinese companies and each have alleged fraud, despite the fact that wrongdoing was not always subsequently proven.

Of course for all the allegations of short sellers, a lack of transparency doesn’t necessarily demonstrate skulduggery.In fact, this has been a point of contention.

This has been a point of contention with the SEC, which is pressuring companies to produce this relevant paperwork as a matter of disclosure to investors (see box on page 35).

Valuation plunge

With valuations plummeting, a few listcos have stepped into the embrace of private equity funds such as Bain Capital, Carlyle and Primavera Capital.

Between 2010 and 2013, 49 companies announced privatisation plans, 25 of which have been completed, according to Tobin Tao & Company, a consulting and advisory firm focused on the US-listed Chinese sector. To date, 19 are still in progress. The typical plan is to privatise the business and then re-list for an improved valuation in Hong Kong or Shanghai at a later date.

But few private equity rescuers are left. Peter Huang, partner at law firm Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom in Beijing, predicts that while an average of 20 companies have delisted annually in the past two years, only a dozen or so may make it out in 2013. This partially has to do with the crunch of finding a buyer at acceptable levels, partially due to an inability to finance the privatisation, and partially that the best listed companies are determined to stick it out.

“A lot of private equity firms have looked these listed companies over and have spotted the ones that are worthy of sponsoring or taking private,” says Huang, who has worked on more than 20 privatisation deals, about half of which are still ongoing. “Others are still quite expensive unless the buyers can find leverage at [an] attractive interest rate and tenor, and private equity firms have become more prudent to the risks.”

Not everybody has given up. The likes of Abax Global Capital, Carlyle and FountainVest Partners are still seeking acquisition candidates, and Focus Media’s financing package has offered listed companies some hope.

But other buyout firms have been burned. These include CDH Investments and TPG Capital, which saw its negotiations with Nasdaq-listed CNinsure fall apart in September 2011 four months after placing a management buyout bid – with the private equity consortium reportedly out US$10 million after due diligence fees.

Baring Private Equity too stepped away from Nasdaq-listed Harbin Electric in November 2010 after the fund and Harbin’s CEO reportedly disagreed on pricing. Harbin, also the subject of short-seller attacks in mid-2011, has since been taken private by Abax.

More recently, Baring withdrew its privatisation proposal for the American depository shares of Ambow Education, citing “unexpected events” on March 26.

“TPG, CDH, Baring – they were so close to closing the deal before they pulled out of their privatisation bid. There must have been something that they really didn’t like,” says the private equity fund manager. “It’s really important to have a thorough due diligence process. You really have to peel back all the layers.”

As share valuations drop and white knights fall away, the cost of being listed has continued to rise. The price of maintaining a listing in the US has roughly doubled since 2010. Legal, auditing and insurance costs have risen to accommodate the post-financial crisis landscape and Chinese companies’ own liabilities after the spate of corporate governance scandals.

There are more than 300 Chinese companies still listed in the US, but that figure continues to dwindle. Citing official data, Reuters reported on January 14 that approximately 50 companies went dark in 2012, severing disclosure ties to the SEC. This compares to about 40 in 2011, and the most since the SEC started keeping records in 1994.

The willingness of some companies to step away from scrutiny has just exacerbated investor scepticism, which hurts share valuations and liquidity and tempts more to go dark themselves. It’s a vicious circle.

Listcos’ self medication

Salvation could be in the hands of these companies themselves, or at least the good ones, provided the regulators are willing to cooperate.

Companies that run genuinely good, profitable businesses have an opportunity to differentiate themselves from their peers. They should begin by considering the responsibilities as well as the benefits of a public listing.

“There are more bad apples than we thought there would be, but there are also many good apples that deserve a chance to get in the door and pick up valuations,” says Jim O’Neill, managing director of Beijing-based Jin Niu Investment Management, which advises private equity funds on their China strategies. “From our perspective, it’s a little frustrating. A common theme is that a lot of listed companies – really reverse mergers – don’t have a sense of responsibility to shareholders. That’s the mentality that has to change.”

The best next step would be for a collection of Chinese listed companies that strongly believe in living up to corporate governance standards to form a committee that conducts investor roadshows and initiates active dialogue with the media and regulators. This would help offer them a voice and allay concerns on their willingness to produce transparent results.

The committee could proactively push corporate social responsibility topics, showcasing how companies treat their employees, how they handle their supply chain and how they conduct their daily operations on a quarterly basis. They should over-tell, offering investors a reason to believe them.

One trend emerging from the global market is integrated reporting, in which a company presents an annual financial report that outlines every aspect of a company’s accomplishments, financial flows and challenges, and makes it interactive so anyone can access it. Through this integrated platform, company chairmen should be accessible to investors; investor relationship departments should speedily respond to queries; and image galleries, videos and testimonials should validate the assets a company owns.

One China executive at a global auditing firm points to Hong Kong-listed CLP Power as a key example of this: “The company’s report goes so far as to even talk about how many people died in accidents working for them – it’s a gruesome and sensitive topic but that is the level in which you have to build transparency...This is what it takes to build confidence. Why would you lie about that stuff? If you’re going to be that honest, people are going to pay attention.”

That sort of transparency should leave no questions as to how a business creates value within its industry and to investors. It would also undercut the predation of short-sellers, which like to play on the fears of investors – something that’s all too easy when targeting tight-lipped Chinese companies.

With enough positive attention and several quarters of companies producing full and transparent results, the investor community would sit up. From there, the committee could admit new members that also vow to uphold the strictest corporate governance standards.

It’s a way to own the message and make a positive public relations statement, and investors will know where to look for access to the most reliable Chinese stocks.

Making compromises

Corporates can only do so much themselves. Any effort they make towards transparency will only work if the US and Chinese stock-market regulators cooperate too.

If these companies are to have a chance at restoring investor confidence, regulators desperately need to reach consensus on giving the public access to mainland company documentation. Doing so would also signal that the two countries can cooperate when the going gets tough, sending a message to fraudulent companies that there’s nowhere to hide.

There are paths that the SEC, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) and China’s Ministry of Finance (MoF) can take to achieve this, though each would require compromise and trust.

One approach depends on the US agreeing to respect China’s ability to regulate and investigate mainland-domiciled businesses. This would require the US accepting Chinese companies’ existing available documents. Then, if the SEC had concerns on any company, it would inform the Chinese investigators, who would be responsible to investigating its operations.

But this also means that Chinese authorities would have the right to punish any company found to be in contempt of any of their agreements or financial inaccuracies as they see fit. This alone may become a thorny issue.

“The US will have to recognise that punishment in China may be more aggressive than in the US, in life and limb usually. That brings up a lot of secondary issues – would the US be all right with a business executive being incarcerated in China, and have that blood on their hands? That would take a lot of trust that China would carry out justice fairly,” says the senior source within a global auditing firm. “That’s surely a conversation that US regulators are having.”

A second solution entails the CSRC and MoF conducting an audit of listcos, and the SEC agreeing to honour the results. These companies would voluntarily open their paperwork and balance sheets to the Chinese regulators to ensure that no state secrets are revealed. The CSRC would deliver the paperwork to the SEC in the US, which would have to trust that the CSRC had truthfully passed along all filings bar material that compromises the country’s security.

Again, complications exist with this approach. The SEC would be likely to question whether the CSRC can detect problems, and whether it would truthfully pass along all documents that don’t contain national secrets.

A final option is for the CSRC and MoF to open the market to allow global auditors to do their jobs, just as other countries do worldwide. It’s a far-fetched solution given the closed nature of China’s onshore marketplace, but it would be the best one.

There may be hope. China’s new administration under president Xi Jinping has included new heads of the CSRC and MoF. Fresh blood could give the country a much-needed opportunity to liberalise its disclosure environment to encourage greater business transparency. Full transparency is probably a long way off, but at least the new regulators can take positive steps to improve companies’ disclosure procedures and investors’ access to information.

Learning the hard way

China should seriously conduct such endeavours. It would be sad news indeed if its unwillingness to offer information on overseas-listed companies destroys their image with international investors.

It would also be counterproductive. One of the Chinese Communist Party’s goals is for the nation to be a more central player in the global marketplace, with its companies becoming more international through mergers, acquisitions and organic expansion.

And the US wants to maintain a positive relationship with China during this process. No good can come from the SEC blocking the US stock exchanges from companies, and it would add insult to injury if it were to systematically kick Chinese companies out of the capital markets, as some theorists believe is possible.

Further, Macquarie research shows that the largest 200 Chinese American depositary receipts had a market capitalisation of more than US$950 billion by July – limiting these companies’ participation in the market would leave a gaping hole.

Ultimately the onus begins with the companies themselves. Rather than use the excuse of Beijing’s recalcitrance to remain opaque, they should volunteer every scrap of information they can, and lobby both the Chinese and US regulators to supply more. The earlier they do so, the faster they will build reputations for openness and fairness, irrespective of the politics between market regulators.

Having a solid track record is the best way to overcome the damage errant companies have caused in recent years – and ensure global stock markets are open to their business. And the predations of zealous short-sellers have amply demonstrated the dangers of lacking clarity.

China boasts some excellent companies. It would be a shame for them to surrender hope of listing overseas.