One of Asia’s best-known billionaires was conspicuous by his absence from the herd of super-rich grazing canapés at the World Economic Forum in snow-clad Davos on January 21.

Masayoshi Son, founder and chief executive of Japanese telecommunications and Internet giant SoftBank, was elsewhere, locked in secret talks with Deutsche Telekom about the sale of its American mobile subsidiary, T-Mobile USA.

Were it to take place, the acq uisition would vault SoftBank to the global top rank in telecommunications. That may sound ambitious, but SoftBank has form in the field of acquisitions. Last year it conducted Japan’s biggest-ever overseas acquisition by acquiring 70% of Sprint Nextel, the US’ third-largest mobile carrier, for US$21.6 billion.

Son is not the retiring type. Announcing the deal to buy Sprint in 2011, he told Japanese reporters: “It’s part of my male ego to strive to be number one.”

But buying T-Mobile and merging it with Sprint, the fourth-largest carrier, will be a harder task. Son needs to win over both Deutsche Telekom and the US’ anti-trust regulators if he is to succeed.

Assuming he can do that (which is far from certain), he then needs to stretch SoftBank’s leverage to unrivalled levels in the world’s mobile telecoms market to fund the purchase.

Perhaps surprisingly, this doesn’t seem to unduly worry the company’s creditors.

“SoftBank has plenty of access to capital,” Jonathan Chaplin, a top-ranked US telecoms analyst at New Street Research, tells Asiamoney. “Banks will throw capital at them at very low rates.”

However it would leave SoftBank highly exposed to the vagaries of the financial markets. The bid for T-Mobile marks a big gamble, even for Son.

US appeal

Son’s desire to build a strong presence in the US mobile market is understandable. China and India have more mobile subscribers, but revenue per user is far higher in the world’s largest economy.

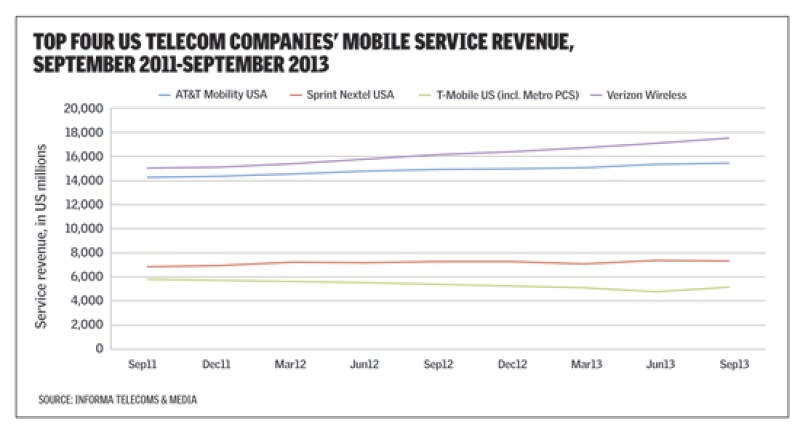

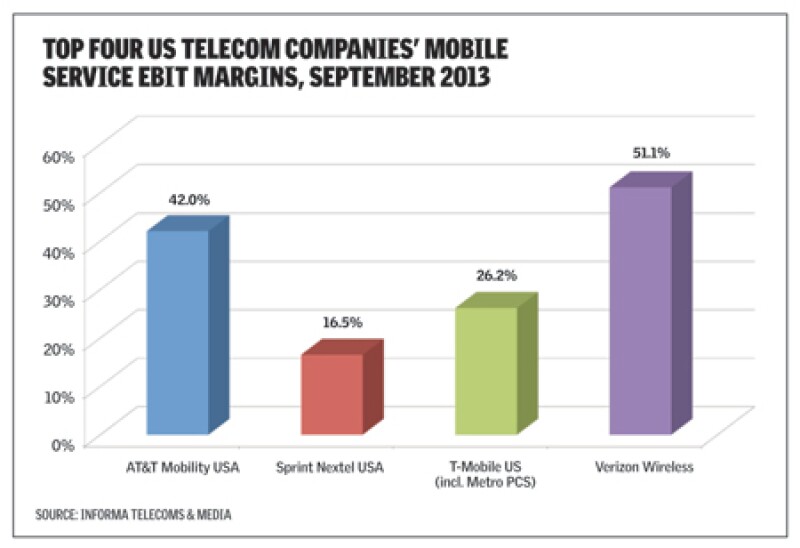

The wireless divisions of the two biggest US telecoms companies, AT&T and Verizon, are both highly profitable. Operating income at AT&T wireless in the third quarter of 2013 was US$4.6 billion on operating revenue of US$17.5 billion.

So profitable is Verizon’s wireless business – it made US$26 billion of operating income from US$81 billion of revenue during the 2013 calendar year – that last year it had to pay Vodafone a staggering US$130 billion to buy back the 45% of Verizon Wireless that Vodafone had owned since 1999. Profit from the deal allowed Vodafone to return £54 billion (US$90 billion) to its investors.

But the success of AT&T and Verizon stands in stark contrast to the US’ third- and fourth-largest players, Sprint and T-Mobile.

Sprint lost an estimated US$3 billion last year and it carries total debt of US$33.55 billion. T-Mobile, which has been adding market share through aggressive marketing, probably managed to make a modest US$184 million net profit in 2013, and has debt of US$22.45 billion.

Both are committed to heavy capital expenditure (capex) to try and match the network coverage of Verizon and AT&T in new fourth-generation (4G) mobile technology that promises much quicker Web browsing and downloads of music and video for mobiles, tablets and laptops.

That begs the question: why is Son so keen to spend billions to buy not one, but two companies that barely eke out a living?

Bigger is better

The reason is simple: economies of scale.

“Let’s say you add as much as US$45 billion in debt to Sprint’s balance sheet from acquiring T-Mobile,” says Chaplin. “But then you also get around US$5 billion of incremental annual Ebitda [earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation] from T-Mobile today, and then US$2 billion to US$3 billion of synergies on top of that.”

The scale game of the telecoms industry becomes particularly relevant when it comes to the costs of building a network.

“Sprint’s capex for last year and 2014 is going to be in the US$8 billion-US$8.5 billion range, and it will be high in 2015. They’ve got 55 million customers. If they acquire T-Mobile, they’ll have 88 million [overall customers] to leverage that fixed investment against. Investment per subscriber would be much lower, because you have to spend the same to build a network regardless of whether you have one customer or 100 million,” Chaplin says.

“Instead of maintaining two networks going forward, you’ll only have one after consolidating the assets. The capex you get rid of as a consequence is huge: US$1 billion or US$1.5 billion a year.”

Oliver Matthew, head of consumer, Japan and Korea at CLSA, sees other synergies flowing from SoftBank’s 2013 acquisitions of Brightstar, the world’s largest specialised mobile distributor, for US$1.26 billion, and its US$1.5 billion purchase of Finnish video-game developer Supercell.

“What are people using their phones for? What do they pay money for? Games. Son bought Supercell because it’s the best game developer.

“With Brightstar, I think the basic reason was they have a very big emerging-market distribution network, and if you look at the trends in the US, it’s all about handset upgrades. What do you do if you end up with 20 million iPhone 5s? You don’t throw them away; you sell them to a telco in Kenya or some such place. That’s the idea, I’m pretty much convinced.”

SoftBank will also gain additional clout with mobile-phone suppliers.

“In Japan, Softbank doesn’t sell Samsung or Sony smartphones,” Matthew points out. “With Brightstar he will be in a much better position to negotiate that deal. It gives them more bargaining power in the Android world, which I reckon is going to be a big theme for them this year.”

Important experience

SoftBank has also been in a similar situation before, as an outsider taking on two big mobile incumbents.

In 2006 SoftBank bought Vodafone’s Japan unit for the equivalent of around US$17 billion. At the time, many thought it would all end in tears.

Vodafone’s Japanese business certainly didn’t look enticing. The UK company had cut back spending on its 3G service in Japan in 2002 and 2003 and, as a result, it lost customers. Between the end of February and end of October 2005, Vodafone Japan shed 103,100 subscribers, while NTT DoCoMo gained 1.65 million and KDDI added 1.82 million over the same period.

SoftBank began turning the ailing business around by aggressively pushing Wi-Fi to compensate for its poorer network coverage, through some brilliant marketing, and by landing the exclusive Japan contract for the new Apple iPhone.

After years of painstaking effort, SoftBank has converted the sickly Vodafone acquisition into Japan’s No. 2 mobile operator by number of customers. It now vies with DoCoMo, the wireless spinoff of the old domestic telecoms monopoly NTT, for dominance.

“It has been a tremendously successful acquisition,” Matthew says. “Son now has a US$100 billion market-cap company. Yes, within Softbank there’s a big portion of Alibaba [China’s successful e-trade company in which SoftBank holds a 37% stake following an astute US$20 million investment in 2000], but its most valuable asset is still the Japan business that they’ve built since taking over Vodafone Japan.”

The value of Son’s company has soared as a result. On March 3, 2006, the day SoftBank confirmed it was in talks with Vodafone, it was worth ¥3.49 trillion (US$29.6 billion at the time). That has almost tripled to ¥9.9 trillion, or US$96.8 billion at today’s exchange rate.

“I was one of those who doubted SoftBank would succeed with Vodafone Japan. But it was a great deal and SoftBank now has one-third of the Japanese mobile market,” says Keiichi Yoneshima, telecoms and Internet analyst at Barclays Capital Japan.

Credit concerns

Japan analysts might believe in Son’s ability to turn a business around, but the international ratings agencies take a far dimmer view.

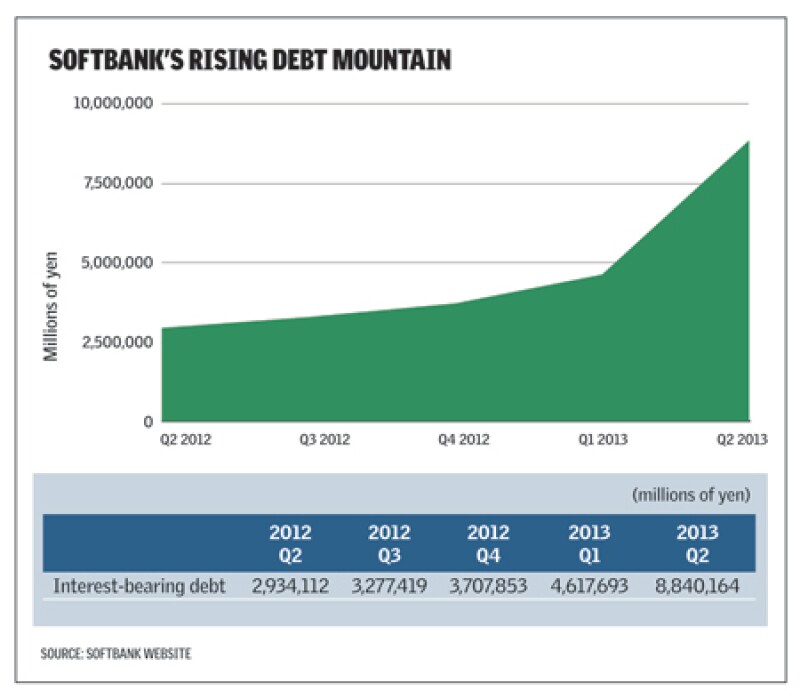

Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s (S&P) already worry about SoftBank’s debt levels. In July both lowered SoftBank’s ratings to ‘Ba1’/‘BBB’ after its purchase of Sprint tripled its interest-bearing debt to 4.6 times Ebitda, versus 1.7 times at AT&T and 1.1 times at Verizon. Buying T-Mobile USA would weaken this further, potentially to 6.5 times, according to Asiamoney calculations.

“I should be concerned if the level of additional debt is what is being reported by the market, from US$20 billion to US$30 billion. That is a very large amount,” Peggy Furusaka, senior credit officer at Moody’s Japan, tells Asiamoney.

She is unmoved by the potential of SoftBank enjoying a windfall from selling down some of its stake in Alibaba as part of a flotation either late this year or early 2015.

“Unless we see the cash, and the cash is really used to reduce debt, equity holdings are just something we recognise as alternative liquidity available if the shares are sold.”

S&P agrees. Makiko Yoshimura, senior Japan analyst at S&P, describes SoftBank’s ratio of debt to equity as “weak” even before the Sprint acquisition. He is sceptical about drawing too many conclusions from SoftBank’s past success.

“The company had success in turning around Vodafone Japan, but that doesn’t automatically mean that they will succeed in America.”

Milena Cooper, financial analyst at Informa Telecoms and Media, says SoftBank’s equity to total asset ratio used to be “bang on the average, about 32%” among the top 40 telcos that make up Informa’s World Telecoms Financial Benchmarks. After buying Sprint, the ratio plunged to about 12%. The only operator with a lower ratio than SoftBank in the top 40 is struggling Dutch telecoms company KPN.

Lending largesse

The ratings agencies may worry about Son weakening SoftBank’s balance sheet even further, but apparently creditors aren’t listening.

Sector analysts think the company could easily raise more debt to buy T-Mobile USA. In part that’s because Son could issue more shares to take advantage of the strength of his company’s valuation.

“The gearing level on [Softbank’s] balance sheet is going to look stretched with another big acquisition,” says Neil Juggins, co-head of pan-Asian research at JI Asia. “But you’ve also got a share price that has gone up five-fold in the last 12 months. It’s not impossible that he could look at an equity-raising.”

Plus Son will be seeking more credit funding at a time when Japan Inc is effectively printing money for fun, as part of the government’s Abenomics drive to bolster economic growth.

“The Bank of Japan has been buying back JGBs [Japanese government bonds] so the banks have got a load of cash,” says Matthew of CLSA. “That’s why nobody cares if Softbank’s ratings are low. The banks will lend to them in this environment.

“If SoftBank does get T-Mobile and bolts it into Sprint, margins go up and cashflow improves, so unless something spirals out of control in Japan and the cost of refinancing debt goes up significantly, I wouldn’t be worried.”

Should the ratings agencies downgrade SoftBank again, “the debt markets won’t give a damn”, adds Chaplin of New Street.

The facts to date support such optimism. On September 13 SoftBank borrowed ¥1.98 trillion in two tranches from a bank syndicate led by Mizuho, Sumitomo Mitsui, Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi, Deutsche Bank and Crédit Agricole to refinance the ¥1.65 trillion one-year bridge loan it had used to buy Sprint in December 2012. It priced the ¥1.1 trillion five-year tranche at 110 basis points (bp) over Tokyo Ibor and the ¥880 billion seven-year portion at 140bp over, cheaper rates than the original one-year bridge loan – despite having been downgraded by Moody’s and S&P a few weeks before.

Facing off with the FCC

With SoftBank’s creditors likely to extend Son even more money, gaining approval from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) looks like the biggest impediment to the merger proceeding.

Getting a green light from the watchdog to buy T-Mobile will not be easy. AT&T can attest to that.

On March 20, 2011 the US telecom company offered to purchase T-Mobile from Deutsche Telekom for US$39 billion. Five months later the FCC blocked the merger on the grounds that it would give AT&T a 43% share of the US mobile market, diminishing competition. AT&T abandoned its bid on December 19, 2011.

The FCC’s willingness to turn down one top-four consolidation is a worrying sign for Son’s bid.

“The FCC for some time now have been stressing the need to have four operators, so how could they argue now that three would be in the public interest?” asks Juggins at JI Asia. “It would be quite hard for them to backtrack.”

It won’t be easy to persuade the regulator, particularly given Sprint’s and T-Mobile’s own statements, and financial positions.

“Sprint’s stock...trades at a very rich multiple; it did so before this T-Mobile deal came along, so the markets aren't concerned about Sprint going bankrupt,” says Chaplin. “The management team is telling you that their future is fantastic on a standalone basis. T-Mobile’s management team is telling you the same thing.”

These messages may have only reinforced the FCC’s belief that it was right to prevent the AT&T bid for T-Mobile USA, and to be equally sceptical of similar requests.

A failed bid could be costly. After it failed in its bid, AT&T had to provide T-Mobile with at least US$3 billion in cash and US$1 billion of radio spectrum as part of a pre-agreed breakup fee. It also included a roaming deal to which AT&T did not attach any value. J.P. Morgan estimates the overall fee was worth up to US$6 billion, equivalent to 15% of the enterprise value of the mooted transaction.

Son may face similar charges if his bid fails. J.P. Morgan estimates today’s enterprise value of T-Mobile USA as US$43 billion, and in a January 6 note, warned that “if the deal broke it would be a massive blow to Sprint to pay anything near a US$6 billion fee”.

Creating a fourth contender?

Yet it’s unlikely Son would pursue this merger without a plan to get FCC approval.

Analysts believe he might try to do so by ensuring that four viable mobile contenders exist even after SoftBank acquires T-Mobile.

The easiest way to do this would be for SoftBank to give Dish, a satellite television company that lost out to it in bidding for Sprint, access to the latter’s network.

“Sprint would do that in a heartbeat,” Chaplin thinks. “That might be one of the things that really sways the FCC.”

While Dish chairman Charlie Ergen can be unpredictable, his company and Sprint are already cooperating on a wireless broadband service in Texas. “It shows you they are able to work together,” Chaplin notes.

Similarly, SoftBank could give radio spectrum to T-Mobile in place of a cash offer, which could remove the risk of the former having to agree to a hefty breakup fee with Deutsche Telekom.

“Sprint has more spectrum than they know what to do with. T-Mobile needs spectrum. It could be almost a costless trade,” Chaplin says.

What is likely is that Son, an inveterate gambler with a shrewd eye for risk, has some ideas about how to wring a go-ahead out of the FCC. If he can do so, Son could end up creating Japan’s most successful international company.

But it would be a business built upon a precariously large pile of debt, most of it originating in Japan. SoftBank could end up becoming the biggest corporate leverage play on Japan maintaining its economic vitality.