China’s big three state oil and gas companies have been among the most acquisitive forces in human history.

Over the past eight years China National Overseas Oil Corp. (Cnooc), Sinopec and PetroChina have bought into rival companies and fields alike, all in part of the obsessive drive of Beijing to secure as much energy sources as possible and ensure that its ever-hungry economy has a meaningful say in the world’s oil and gas markets.

The country’s need for energy is well known. After over a decade of 10%-plus gross domestic product expansion the country’s economy consumes more energy than ever, and it is still growing at over 7%.

But its energy production has not kept pace with this growth. Lawrence Lu, director at Standard & Poor’s (S&P) notes that the country’s consumption of crude oil has nearly doubled over the past 10 years, while domestic oil production has risen only 25%. The country had to import almost 60% of its crude oil needs last year, in 2012.

Its insecurity about such a heavy reliance on imported energy sources has led it to push its big oil and gas companies to buy big abroad. They’ve done so in a major fashion, spending an estimated US$92 billion on foreign acquisitions and joint-ventures since 2009. The corporates spent US$35 billion last year alone and US$25 billion in the first seven months of this year.

But there are relatively few obvious companies left to buy, which is going to push China’s energy majors into seeking more part nerships and smaller acquisitions. They will also have to increasingly invest into non-mainstream energy production, including fracking.

Aside from maintaining their appetite for further acquisitions, albeit on a potentially smaller scale, China’s major companies are also likely to try improving their domestic extraction capabilities. Two particular opportunities exist: fracking for oil and gas, or coal gasification.

The emphasis of the companies might be set to change but one thing holds true: China’s big three energy players will remain under pressure to grow their energy production. It’s going to be costly, and they will need to fund it.

Buying spree

China’s three oil and gas majors have largely sourced more energy resources through a spate of acquisition over the past few years. Cnooc’s acquisition of Canada’s Nexen for US$15.1 billion in February offered the most recent example.

Bankers and analysts alike anticipate that the companies would remain very active in the M&A market, but a lack of obvious targets could well cause the pace of this activity to decline.

“It’s natural to assume that the acceleration of Chinese energy outbound investment will dampen,” says Will Rathvon, global head of natural resources for ANZ. “The big state-owned enterprises will still do acquisitions but they are likely to become more strategic, such as acquisitions in China itself, or exports that are LNG (liquified natural gas)-backed.”

Instead of purchasing entire companies, China’s majors could look to enter partnerships to exploit proven deposits. One area in which such an arrangement would make sense is a huge natural gas find off of the coast of Mozambique in Africa. A set of exploration companies have discovered huge pockets of gas in recent years, with the offshore Rovuma basin estimated to hold 130 trillion cubic feet of natural gas.

The LNG possibilities have greatly excited many companies, and led Thailand’s oil and gas producer PTT to outbid Royal Dutch Shell to buy UK company Cove Energy for US$1.9 billion, which has an 8.5% stake in a block at the site. Experts say that the exploitation of Mozambique’s gas reserves could ultimately lead to 10 LNG export facilities, along with additional plans for fertiliser production and local power plants.

“There’s more gas there than Mozambique knows what to do with,” says Rathvon.

So far no Chinese majors have bid for any units in the project. However it’s unlikely to be a coincidence that Mozambican president Armando Guebuza made a week-long visit to Beijing in May, to discuss improving bilateral trade. Chinese companies are already building a ring road and bridge near the capital of Maputo.

It will surprise very few were Cnooc or PetroChina to announce acquisitions in the country’s gas find very soon.

Fracking frustrations

Acquisitions aside, China’s companies have also been looking with great interest at the success of US’ energy boom.

The country has enjoyed a sudden glut of gas following the efforts of a set of local energy companies to extract shale gas and oil via ‘fracking’, or hydraulic fracturing. The unconventional method of fuel extraction now accounts for a quarter of the country’s gas needs.

That has led to the inevitable question: does China have similar opportunities, and can it do the same? The respective answers to these questions are: yes, and no – at least not immediately.

The US’ geology lends itself to the exploitation of shale reserves. The bedrock in which the oil and gas is to be found exists in horizontal seams at an average of two kilometres beneath the surface. Mining companies have been able to drill horizontal wells to access the resources.

China’s geology presents far harder conditions. Experts believe most of its shale oil and gas deposits are found around Sichuan, a more forbidding, mountainous terrain that lacks good infrastructure. It’s also much deeper, at an average of around five to six kilometers down.

“China has got more domestic gas potential than oil potential but unlocking it will take time,” says Rathvon. “The US has exploited its shale gas reserves through conventional well technology, but that doesn’t necessarily translate to China. The geology there is more complex and deeper in some areas, while they lack the pipeline distribution to get to centres in which they need it.”

These difficulties are not insurmountable, particularly for a country whose leadership can be as single-minded as that of China. But these factors mean it will prove more costly to exploit.

“The bottom line is in terms of price,” says Peter Gastreich, head of oil and petrochemicals research in Asia at UBS. “In the US fracking becomes a cost-effective business when the gas costs US$4 per thousand cubic feet. But in China the minimum wellhead gas price would need to be in the range of US$9-US$10 per thousand cubic feet to make exploiting its reserves viable.”

That may sound optimistic now, but Rathvon believes it’s just a matter of time before gas prices rise once more. “I don’t think that the US exporting of gas will lead to lower gas prices in the next five to 10 years. Demand is outpacing the new supply.”

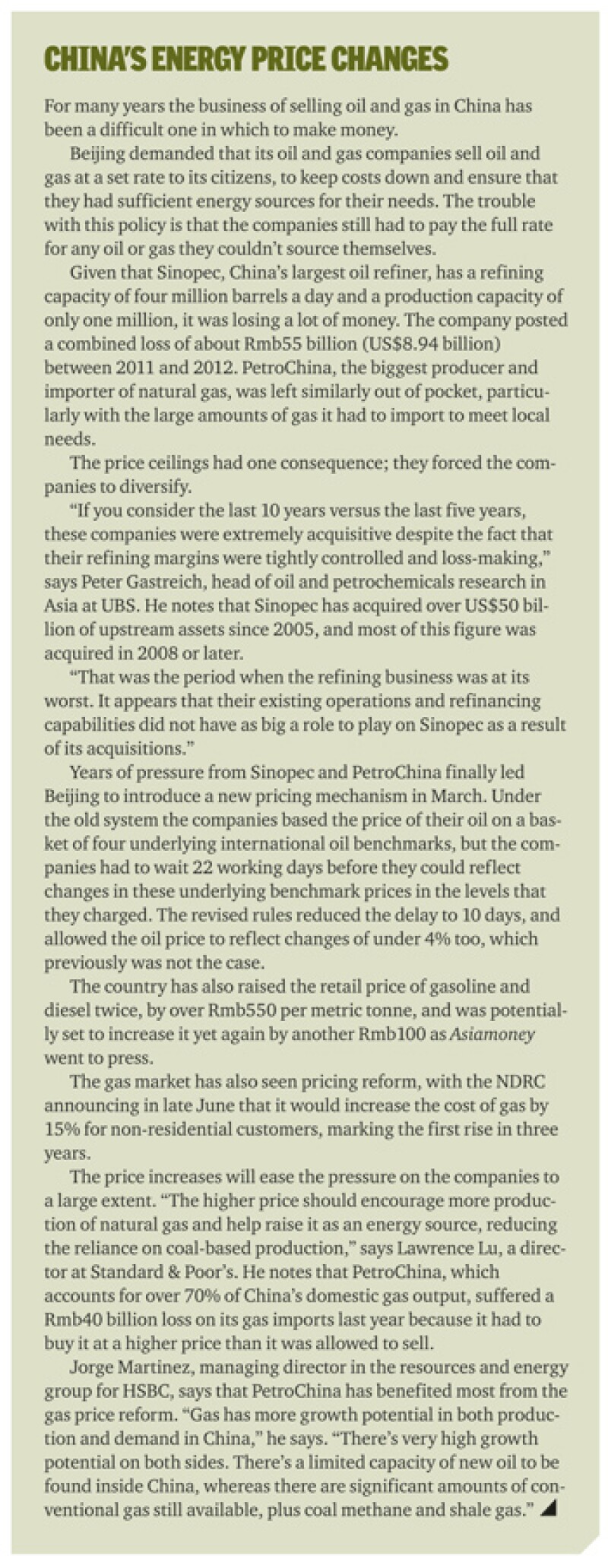

Political pressure

Beijing is certainly keen to begin exploiting the reserves as soon as possible.

Gastreich says that the government has targeted shale gas extraction of around 6.5 billion cubic metres (bcm) per year by 2015, and then 60-100bcm of natural gas production by 2020. Those are ambitious targets, given that today only four shale gas projects are actively drilling in China. Sinopec may be the first to develop by the end of 2014, but along with PetroChina’s efforts, shale gas production will probably reach just 1bcm-3bcm by 2015.

One way the government could bolster shale gas production would be to encourage the private sector. The three energy majors tend to dislike exploration and Greenfield risk. That offers the opportunity for independent exploration companies. China could even invite in foreign corporates to take a look-see as well.

Alternatively, the three energy majors could invest in shale production in other countries. ANZ’s Rathvon notes that one such example could be the Cooper Basin in Australia, in which Chevron Texaco bought the interests in two blocks from Beach Energy for around US$350 million early this year. Beach had previously estimated that there could be up to 300 trillion cubic feet of gas beneath its land in Australia.

Chinese companies could buy stakes in such blocks too, possibly in a partnership with foreign companies. However, bankers warn that this won’t be a silver bullet to their domestic needs.

“The Chinese could go in with an alliance and in order to gain the technical aspects of fracking in a specific geology in one basin. But while some of the technology would be transferable to its onshore needs not all of it would easily be so; that’s the warning on the label,” says Rathvon.

Jorge Martinez, managing director for the global resources group at HSBC agrees. “It will take some years for shale gas production to take off [in China],” he estimates, citing the depth of the deposits, the geologic differences and the fact that fracking requires a lot of water, which China lacks in abundance.

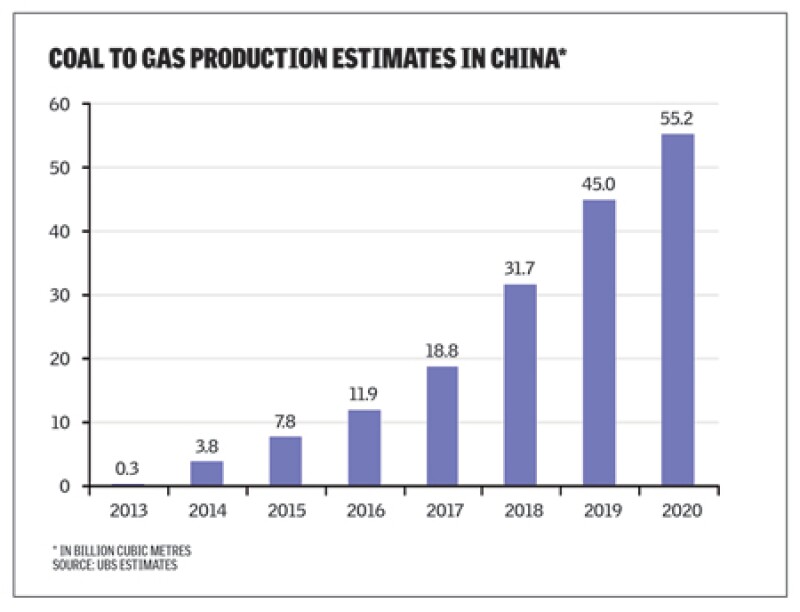

With shale gas likely to present mid-term opportunities, PetroChina is likely to seek out other forms of gas exploitation instead. Coal gasification particularly interests the company.

Coal gasification involves mixing coal with steam and oxygen under high pressure and temperature to produce a synthetic gas, which can easier be delivered to power plants for burning. It is a dirty way to create energy – UBS estimates that the entire process of converting the coal to gas, transporting it and then burning it leads to carbon emissions that are 30%-40% higher than merely burning the coal.

But there’s a definite economic advantage to doing so and jobs are also created in China. Liquified natural gas imports from Qatar or Australia cost close to US$18 per thousand cubic feet, which the local energy majors (mostly PetroChina) have to sell locally at around US$10-US$12 per thousand cubic feet based on existing city gate prices along the eastern seaboard. Producing gas directly such as via coal circumvents this cost, particularly as new incremental sales can be supplied to power plants through more lucrative contract prices following NDRC gas price hikes as of July 10 this year. UBC predicts that coal-to-gas will surge in the coming years.

Funding needs

The need of China's energy producers to keep adding to their production capabilities has one obvious consequence: they will have to spend a lot more money. And even the three largest producers lack infinite amounts of ready capital.

S&P’s Lu notes that the debt levels of the three energy majors are rising faster than their assets, although not yet to worrying levels. He warns that a big rise in the cost of oil in the world would also hit their bottom lines again, as it would once again leave them selling at a loss.

Bankers and analysts alike anticipate that the companies will have to raise more funds to pursue their ambitions in the coming few years. And the poor state of China’s local equity market means that debt issues could become the favoured funding choice.

All three SOEs have already demonstrated their interest in this market this year. On April 19 Sinopec raised US$3.5 billion through a four tranche bond offering. It was followed by Sinochem Hong Kong Holdings, China’s largest petrochemical company, with a US$1.3 billion bond sale in April, and then Cnooc with a US$4 billion bond issue on May 7.

“The big energy companies will have a continual need for capital so they’re likely to remain bond issuers,” says a senior energy banker. “China’s resources need will only continue to increase so it’s likely they’ll be regular capital market users to pay for their ongoing expansion.”

“Cnooc and Sinopec issued dollar bonds because the dollar rate is still fairly low and they’ve acquired a lot of companies that were priced in US dollars in recent years,” adds S&P’s Lu. “It makes sense for them to borrow in dollars and think they will continue to come offshore to borrow.”

There’s also the possibility of equity issues down the road. Rights offerings would be one option, as they offer existing investors the chance to avoid dilution. An alternative would be for the companies to spin off assets, either for direct sale to private sector companies, or via public listing.

Sinopec could potentially take this option, particularly given the background of chairman Fu Chengyu. Fu was formerly chairman of Cnooc, and during his tenure the company listed its engineering and pipeline subsidiaries as separate entities on the Hong Kong stock exchange.

Some bankers believe he could well seek a similar restructuring at Sinopec, in order to help it raise more capital for its capital expenditure needs. Others are less positive, arguing that Sinopec’s engineering and pipeline businesses are held by the wholly state owned parent company, not the listed unit, and that Beijing might not want to allow investor scrutiny of those operations.

China’s oil and gas companies are being driven by the country’s incessant need to source energy. They will continue to be under pressure to source more oil and gas, be it through acquisitions or utilising new technology. It’s going to get more difficult and more costly.

China’s energy SOEs might not acquire to quite the same degree, but they look set to remain voracious users of the capital markets.