The potential of Indonesia's sukuk market is obvious. The country had a gross domestic product of $888.5bn at the end of 2014, when it posted growth of 5%, according to World Bank data. It has a population of more than 200m people, the vast majority of which are Muslim. It also has a well-respected debt management office with a keen eye for market development. There is no reason it should not also have a vibrant Islamic bond market tapped by a diverse range of corporations.

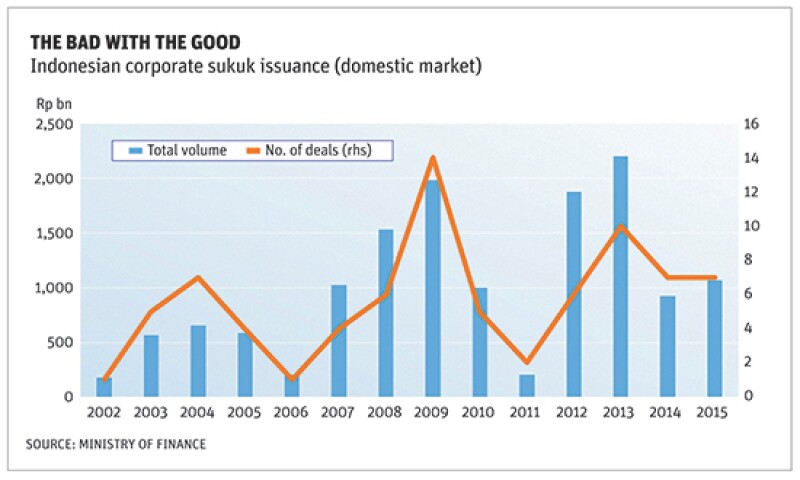

But the market has struggled to gain ground in recent years, despite sizeable gains in both Indonesia's economy and its domestic debt market. Corporate sukuk issuance in the country has certainly come a long way since Indosat opened the market with a Rp175bn ($12m) deal in 2002, but the trend has been far from steadily upward.

Corporate sukuk issuance in the country is scant enough that strong trends in the data should not be expected, but it is still remarkable that the market posted volumes of Rp1,025bn, Rp1,534bn and Rp1,980bn between 2007 and 2009 — and then just as quickly collapsed. The market's volumes were cut in half in 2010, and by the end of 2011 bankers had managed to close just two deals that year, worth a paltry Rp200bn.

Corporate sukuk issuance is already worth Rp1,066bn so far this year, after eight deals. There is little doubt that the market looks a lot better than it did four years ago. But volumes in the market are such that it remains an open question whether 2016 will be a boom year, or a bust.

Follow the leader

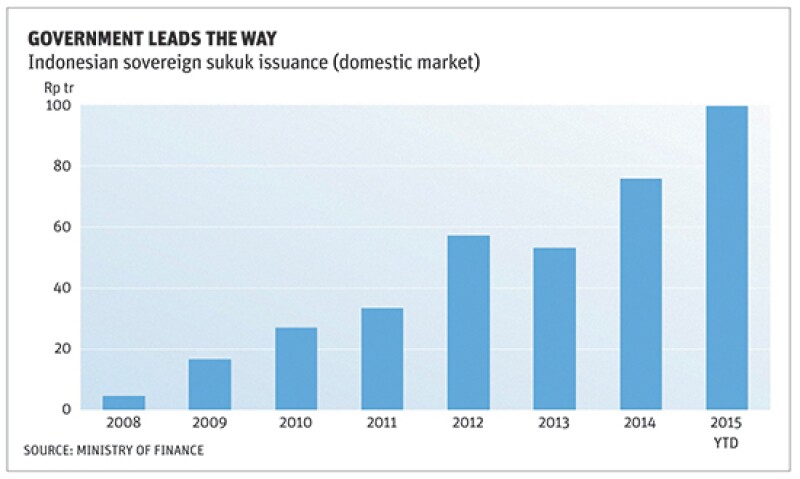

There is little doubt that Indonesia's government has, at least, seen the benefits in selling Islamic bonds. Nor is it hard to see why. Indonesia has an growing economy, a budget deficit of more than 2% of GDP and an infrastructure funding plan of more than $400bn over the next five years. It is little surprise that any form of reliable debt funding would pique the interest of funding officials.

The country now turns to the Islamic bond market for around a fifth of its overall funding plan. It pays up for the privilege, but the spread between Islamic and conventional bonds has slowly been falling in the last few years, which may explain in part why the proportion of government funding going to the market is creeping up.

The government is planning to meet around 23% of its funding plan in the Islamic bond market this year, compared to 17% a few years back, says Suminto Sastrosuwito, director of Islamic financing in Indonesia's debt management office. That works out to more than $7bn of Islamic issuance this year, based on the government's project funding plan of Rp452tr ($31.3bn) for 2015. It includes a mix of foreign and domestic currency issuance, with the offshore markets representing about 25% of overall issuance.

Indonesia has long been regarded as one of the more savvy emerging market issuers in the global market. It has already developed a reputation with dollar bond investors for being a reliable issuer of benchmark-sized deals, returning repeatedly with transactions that rarely draw ire from investors the way some of the region's other borrowers are apt to do. The sovereign has also recently turned to the euro market, as well as issuing its first Japanese yen deal on a stand-alone basis. But on a domestic level, development is all about the sukuk market.

Indonesia sold its first Islamic bond in the domestic market in 2008, when it raised Rp4.7tr from fixed rate bonds. It has added a variety of formats — including retail sukuk, Islamic T-bills, and project-based sukuk — since that opening act and last year the country raised Rp75.54tr from sukuk. It has already beaten that this year, hitting Rp99.35tr of issuance by the middle of September.

These deals have been helpful in developing the Islamic finance market in Indonesia, which still only represents about 5% of banking assets in the country. But it appears to have had little impact on the eagerness of corporations to come to the market for funding.

It is perhaps in the foreign markets where the government has probably had the most influence on Indonesian issuers tapping the Islamic bond markets. Indonesia first turned to the dollar sukuk market in 2009, selling a $650m five year bond, and it has tapped the market every year since. In May this year, it managed to close its biggest Islamic bond yet, selling a $2bn 10 year bond. Indonesia now has $7bn of dollar sukuk outstanding, more than any other sovereign, according to data from the Ministry of Finance.

The country's corporations have followed to some degree. Garuda Indonesia was the most recent example. The company made its debut in May, showing there is plenty of demand from international investors by raising $500m from an unrated debut transaction, although some investors at the time suggested the lead managers kept a large portion of the deal. Whether or not they have appealed to investors across the market, these deals have worked for the issuers.

Islamic, meet infrastructure Besides the ubiquitous discussion of just when the US Federal Reserve will raise interest rates, there are two talking points that come up all the time in discussions with bankers trying to increase their business in Indonesia: Islamic finance and infrastructure finance. It is unsurprising that infrastructure finance has taken centre stage. There is a certain take-it-or-leave it feeling about the Islamic bond market. It would be good to have a fully developed market, bankers say, but it is not essential. The same cannot be said for a big boost in infrastructure spending, which is crucial for any emerging market hoping to turn short-term growth into long-term structural development. But some brave souls are at least considering the possibilities of putting the two together, marketing an infrastructure bond in sukuk format. The government has already issued sukuk where the funds are earmarked for a specific project, allowing Islamic investors to benefit from participation in a project, but so far private sector issuers have not followed suit. “The Islamic concept of financing actually fits very well with infrastructure finance,” says a Jakarta-based executive in the infrastructure segment. “But it is just a matter of educating the market.” This is one area that could create a real source of supply of non-government Islamic bonds in Indonesia over the next few years. But despite the optimism that progress in this regard is about educating investors, it may be more accurately about incentivising them. The first truly private Islamic infrastructure bond, and the concessions it gets from the government in terms of tax, for instance, would prove an early test case for the bold idea of pushing together two of the major talking points in this market. With any luck, bankers will soon be down to one topic of conversation. Besides the Fed, of course. |

But it is somewhat easier for funding officials to make the adjustment to issuing sukuk in the international market, because although there is usually still some spread to be paid between sukuk and conventional bonds, that spread has fallen dramatically over the last few years, whereas the domestic market is more stubborn.

Middle Eastern investors, in particular, are the saving grace of the international Islamic bond market. They help ensure that yields on dollar bonds, especially those from well-regarded issuers, can keep falling as they become more familiar to the investors. This is counter to what conventional investors would like, of course: they have long been used to an automatic premium when conventional issuers turn to the bond market in sukuk format.

Besides, the sporadic issuance of dollar bond sukuk from Indonesian corporations is going to make little difference to the vast majority of the country's issuer base. Indonesian issuers are reasonably frequent issuers in the dollar bond markets, but foreign investors tend to like repeat issuers or credits from select sectors. For those of the country's issuers that are left out in the cold, the Islamic finance market could be a game-changer. But a lot of work needs to be done first.

Chicken little

There are few conversations more likely to bring up the analogy of the chicken and the egg than ones concerning financial reform. Does swap liquidity need to be improved before foreign fund flows can be increased, or are foreign fund flows necessary to help increase swap liquidity? Do investors need more infrastructure bonds before they can build teams to focus on analysing deal risk, or do more investors need to analyse deal risk before infrastructure bonds can come to the market?

In the sukuk market, there are a number of chicken and egg questions, but one of the most obvious is one that affects all markets that are at an early stage of development: do we need an increase in the investor base to drive more issuance, or more issuance to drive an increase in the investor base? It may seem obvious that the answer is that both should happen together. But that does not help much.

Investors complain that there is simply not enough issuance in the market. They do not see the purpose of dedicating resources to studying and understanding Islamic bonds if there are not going to be enough credits for them to buy, credits that are sufficiently diverse that they can realistically build a sukuk portfolio in the country.

This does not mean that all investors are shying away from the market, of course. There are several shariah-focused funds operating in the market, and plenty of other investors argue they are agnostic between conventional and sukuk issues. But many investors have still not come to terms with the market. As a result, they are sticking to the sidelines. The chicken and the egg strikes, and issuers complain that a lack of investors makes preparing for a sukuk issue not worthwhile.

There are some factors that could help increase Islamic bond issuance in the country. The most common request from market participants is for the government to consider tax reform, scrapping capital gains tax on sukuk bonds. This is something that the government has so far proved reluctant to do, partly because the Dutch law system makes this something of a legal headache for regulators.

There is another oft talked about development that could help develop the corporate sukuk bond market in Indonesia: the attempts by banks to increase cross-border flows between ASEAN capital markets.

This may not be as easy as it looks at first glance. Malaysian investors appear the obvious source of demand for Islamic bonds from Indonesian corporations. But their own ratings restrictions would be likely to limit any mass move to scoop up Indonesia sukuk.

These investors have, however, increased their holdings of Indonesian sovereign sukuk. It may be only a matter of time — or timely credit enhancement — before they move on to at least the country's flagship corporations. Middle Eastern investors are another obvious source of demand.

“With Indonesia's economic stability and infrastructure development, I believe that our sukuk market still has potential growth that could attract offshore investors including Malaysian and Middle Eastern investors as well as [those from other] Asean countries,” says Suminto.

He points out that the participation of Islamic and Middle Eastern investors in the sovereign's dollar sukuk issuance has been steadily increasing: from 30% in 2013 to 35% in 2014, and up to 41% when Indonesia tapped the market with its $2bn deal in May. These investors could easily be enticed into the domestic market if the opportunities proved big enough, and frequent enough.

The government, for its part, will continue to fly the flag for the Islamic bond market.

In the international market, the country has managed to push the spread between its sukuk and conventional down from as high as 40bp in 2010 to a minimal level today, says Aaron Russell-Davison, head of debt capital markets at Standard Chartered Bank. It will continue to educate investors with the goal of pushing down the spread in its domestic market. That education and marketing process will be driven in large part by lowering its own funding cost, but it is at least going to reap clear benefits for the corporate sukuk bond market in the country.

There does not appear any major attempt underway to kick-start an Islamic bond revolution in Indonesia. Infrastructure funding is, understandably, considered a more important topic. But those hoping to see the development of a shining sukuk market in Indonesia can at least take comfort that at least one segment of the market is going from strength to strength. The government is making sure of it.