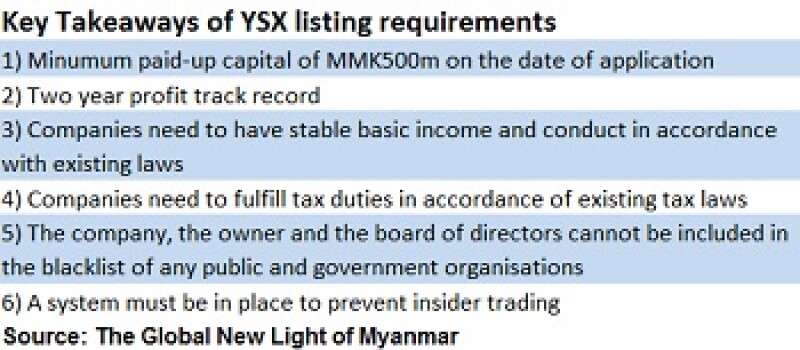

The listing criteria were published in the August 14 edition of state run newspaper The Global New Light of Myanmar, and comprise 17 requirements that companies will have to comply with in order to list on the YSX.

They include qualitative standards relating to corporate management, corporate governance, compliance, disclosure of corporate information, insider trading, internal management and internal control.

The criteria were drawn up after long deliberations between the exchange and the government, and take into account the state of companies in the country and the lack of history of an effective exchange market. As a result, most of the rules are fairly well prepared and practical, said a local source who advised on them.

The establishment of the YSX may be new, but stock trading can already be done via an over-the-counter (OTC) market called the Myanmar Securities Exchange Centre. The YSX, though, will be the first modern exchange in the country. And it has been a long time in the making.

High hurdles

A joint venture agreement between Japan Exchange Group, Daiwa Institute of Research and state-owned Myanmar Economic Bank to set up the YSX was signed last December, but talks between the three parties started as early as 2012.

The bourse was expected to come to fruition in October 2015, but has now been delayed until after the country’s general elections, which are due to take place on November 8.

Sean Turnell, a professor at Macquarie University who specialises on the Burmese economy, reckons that activity on the YSX will initially be minimal at best. That is because the exchange has set the bar very high, making it hard for most companies to comply with the regime.

“Most of the requirements are fairly standard, but the one that stood out for me was the two-year profits track record, which will really block the market for startups and smaller companies,” he said. Another requirement he found strict was the minimum paid-up capital of MMK500m ($400,205).

Erring on the side of caution may be no bad thing given the experience of neighbouring Cambodia and Laos. Both countries opened their stock exchanges in 2011, but issues with compliance, disclosure and the general quality of companies mean that listings have been few and far between.

As of August 20, there were only two stocks trading on Cambodia Stock Exchange. The Laos Stock Exchange has just four to its name.

“They’ve [Myanmar] set the hurdles quite high and I think the signal they’re trying to send out here is they want to have a proper functioning stock market with blue chip names rather than repeat the disasters of Cambodia and Laos,” said Turnell.

Not all good

Satoshi Nakamura, a Tokyo-based partner at law firm Mori Hamada & Matsumoto, agreed that the listing requirements are fairly strict, but highlighted several grey areas that still needed to be addressed.

What caught his eye most was the fact that no companies included on any government blacklist would be allowed to list on the YSX. Companies that the government considers have committed some sort of wrongdoing can be blacklisted, but such lists are not public, raising transparency concerns.

In addition, the listing criteria were unclear whether compliance with laws and fulfillment of tax duties would be required only in the future or would be retrospective. If it were the latter, then the number of eligible candidates will go down.

Also missing is any requirement for a minimum float, a standard mechanism in most exchanges around the world. “To secure a certain level of and improve the trading volume of stocks, a minimum float requirement is worth consideration,” Nakamura said. “But due to the lack of history of a stock market, those requirements were probably deliberated but shelved for the time being.”

The first company to list on the YSX is likely to be First Myanmar Investment (FMI), one of the largest conglomerates in the country and the sister company of Singapore-listed Yoma Strategic Holdings.

According to the source in Yangon, FMI is the only firm that is ready to list once the exchange is in place and also big enough to benefit from capital aggregation from a stock market.

“Its affiliate Yoma is adhering to the standards of the SGX, which is arguably the most advanced bourse in the region, so FMI will naturally have no problem meeting the YSX criteria,” he said. “It’s also one of the biggest firms in the country, which makes it a natural candidate as well.”

Far from ready

While the company might be ready, the same cannot be said of the country. Everyone that GlobalCapital Asia spoke to for this story said the country still had some way to go before a listing could realistically take place.

Top of their list of reasons was the fact that the Securities and Exchange Commission of Myanmar (SECM) has yet to award any securities companies a licence to operate on the YSX. The regulator will need to do that soon to have any chance of launching the YSX by the end of the year, since securities companies will need to undergo extensive tests to make sure IT systems for trading are working, said Nakamura.

There are also concerns about investor education. While the regulator has conducted a series of stock market seminars for investors, with the help of Daiwa, some question whether this is sufficient. The priority so far has been on educating the staff of the regulator itself. Nakamura says this is also important, but is only one part of the entire market.

Turnell at Macquarie University has a more basic worry. “The important question to ask is whether Myanmar is ready or even in need of a stock market,” he said. “To be honest, it’s mostly symbolic to show the world the country has a modern economy, and no matter where you cut it, it’s not going to do very much.

“The only thing they need to make sure is it’s not going to do any damage, which is why strict listing requirements and proper investor education are needed.”