CEEMEA primary bond market volumes for 2022 cannot be described as anything but appalling. By mid-November, with only a small amount still expected to be issued before the end of the year, there had been just $109.51bn printed, compared with a full year total of $257.59bn in 2021, according to Dealogic data.

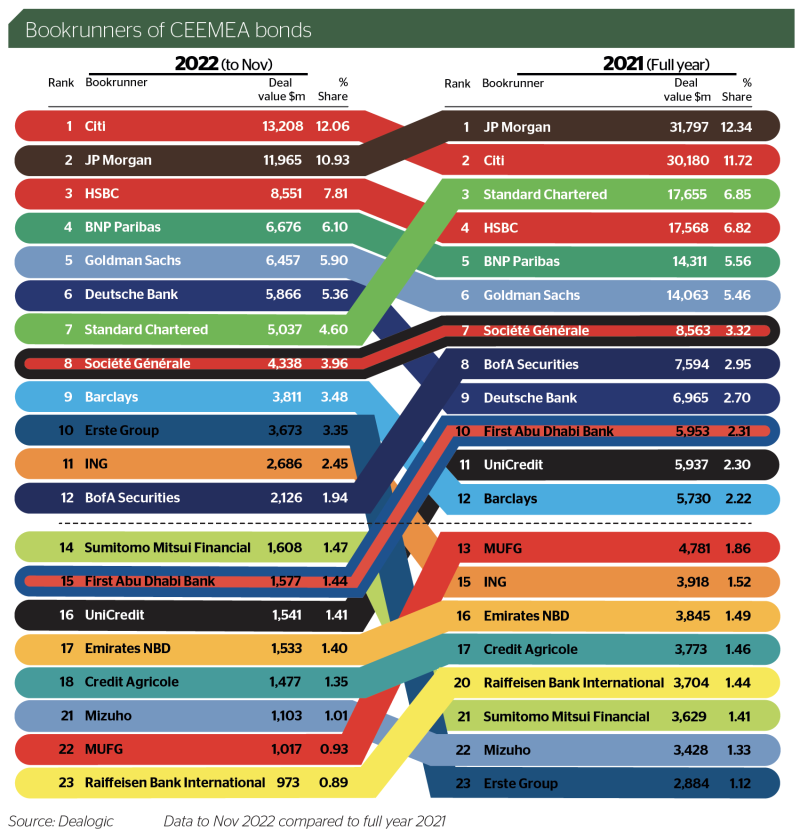

Citi, in mid-November, looked to be triumphant at the top of Dealogic’s CEEMEA league table of bookrunners, taking one of its usual dominant positions alongside JP Morgan.

“The EM bond business in CEEMEA remains largely a two horse race, and there is a big gap between those banks and banks three, four and five in the league tables,” says Tommaso Ponsele, co-head of European corporate and CEEMEA DCM at Citi in London.

Not one bank in the top 10 for 2022 was in same position at the end of 2021. First Abu Dhabi Bank and Bank of America fell out of the top 10 entirely in 2022, replaced by Erste Bank and Barclays.

The reasons for the changes in positions and volumes are not straightforward. One obvious factor was the removal of all potential Russian and Ukrainian bond business in February. In 2021 there was $20.94bn of bond business just from Russia alone, and a further $3.89bn from Ukraine.

The CEEMEA bond houses that were especially strong in these countries suffered an immediate blow. Though many of the Russian bonds were already being placed by local Russian houses such as VTB Capital because of previous rounds of sanctions, some international banks were still active. JP Morgan had in 2021 been third for that business, for example. Citi was only fifth, which may have gone some way to explaining how Citi looked to have nabbed the CEEMEA crown from JP Morgan by mid-November in 2022.

Can’t print, won’t print

Another factor was the rocketing yields in Turkey, linked to unorthodox monetary policy and high inflation, which meant that apart from the sovereign the only other two issuers to tap the market from that country in 2022 were Coca-Cola Içecek and Istanbul.

The sharp rise in US Treasury yields throughout the year meant that several high yielding corporate issuers in Africa also looked locked out of the market.

Meanwhile, in the areas of potential issuance that remained — such as core CEE and the Middle East — issuers balked at the sky-high new issue premiums demanded of them. Across the Gulf in particular, bond volumes took a beating as oil prices shot up as a result of the war in Ukraine. Revenues for oil producing nations increased, making them less reliant on bond market access and even less likely to pay the new issue concessions investors were demanding as compensation for the US Treasury volatility.

According to Dealogic, $158.07bn was printed from the MENA region in the full year 2021. By mid-November 2022 only $59.62bn had been sold. From the CEE region, $49.89bn had been sold by mid-November, compared with $99.52bn in the full year 2021.

But although the volumes were smaller for each region, their proportions of the whole were markedly different, which goes some way to explaining why the banks most focused on the Middle East — such as Standard Chartered — have fallen in league table position in 2022 rather than risen, as might have been initially expected with the removal of the Russian business.

“We had over 50% of our volumes come from central Europe in 2022, which has never happened before but we think will continue to be a theme,” says Stefan Weiler, head of CEEMEA DCM at JP Morgan.

There is always next year

Banks are hopeful that 2023 will be different.

“In terms of volumes, 2022 was the bottom — there is funding to be done,” says Iman Abdel Khalek, co-head of CEEMEA DCM at Citi in Dubai. “Even in the last six weeks we have seen more of an adjustment to the new rates environment and investors starting to engage. CEEMEA volumes will pick up and we will return to something that looks like the average of 2018/2019 volumes.”

In 2019 $225.9bn was printed from CEEMEA. In 2018 $191.3bn was sold.

“The second half of 2023 could be busier than the first and from that point forwards it will be game on,” says Nick Darrant, co-head of EMEA fixed income syndicate at Citi. “Investors will be cautious of a repeat of 2022, when they came in at the start all guns blazing only to get burnt.”

Even as the Russia business looks to be gone indefinitely, there is hope that with maturities on existing bonds piling up and debut issuers to come the CEEMEA bond business can still grow.

“For 2022, non-sovereign Middle East and Africa maturities were $5.2bn,” says Alex Karolev, head of CEEMEA syndicate at JP Morgan in London. “In 2023 they are $28.6bn. And the year after that it’s $45bn. It’s difficult to say how these will be managed. The majority will likely be refinanced with bonds, but the syndicated loan market — which had been more robust than the bond market in 2022 — will likely also kick in and some may be paid down with cash. But these countries are still growing and investing a lot and I think the bond market remains a natural option for them.”

He points out that the overwhelming majority of CEEMEA issuers throughout 2022 have had access but chosen to not print, which also brings hope for 2023.

“The rationales have been varied,” Karolev says. “Some didn’t like the new issue premiums, some thought rates would come down, some just didn’t like what they were being asked to pay versus their last deal. It has taken a lot of the year to accept that normal is different to what these issuers are used to.”

There may also be some boost to 2023 volumes because issuers that were planning to print in 2022 delayed their deals because of the volatility.

“We are still sitting on mandates from the fourth quarter of 2021,” Weiler says. “There have been lots of transactions delayed but they remain in the pipeline.”

Determined duopoly

Citi and JP Morgan for nearly a decade now have passed the CEEMEA league table crown between them — the last time another bank occupied the top position in this league table was 2013. The dominance of these two banks — with market shares of 12.06% and 10.93% respectively in 2022 — makes for interesting projections for their futures in this business, with questions arising over whether they can still grow their market shares from here and at what cost to the broader CEEMEA bank landscape.

“They say that when Alexander the Great was 33 he cried salt tears that there were no more worlds to conquer,” Darrant says. “So, indeed, where does one go from here? My mantra is that complacency will be punished and that we must continually renew and refresh our offering. We can’t create new countries but there are certainly new government-owned entities and corporates to come. EM is a growth market and can withstand shocks — it will bounce back even if it now grows in a different direction.”

Ponsele adds that while of course Citi wants to remain at the top of the league table, the team wants to do that by being the “go-to shop” for the most strategic deals supporting acquisition financing, important maturity extensions and hybrid capital.

“There are only two houses strong across every region in CEEMEA,” Abdel Khalek says. “Some teams at other banks may need to be reshaped but ours are unlikely to be impacted by the lower volumes, even while others retreat.”

That potential retreat was in sharp focus in November as Credit Suisse — once a big player in emerging market bonds — announced that it would be winding down that business, firing much of its EM team, including long-serving syndicate manager Dhiren Shah. There are fears that other banks will follow, though some in the top 10 — as well as Citi and JP Morgan — say the business will still be viable for many houses.

“EM business at the banks isn’t just about bonds,” says an EM syndicate manager at a third bank. “There are so many aspects — including bilateral lending, derivatives, primary dealership, cash management and structured products — that can be offered as alternatives. So even after a bad year for EM bond volumes, banks are still able to utilise other sections of their institutions to assist clients and generate P&L.” GC

Update Jan 2023:

By the end of the 2022 JP Morgan had reclaimed the top position. See table below.