How often have national politicians wrangled and railed over the European Union’s prim disapproval of government borrowing?

Euro membership requires adherence to the Stability and Growth Pact, which is supposed to limit borrowing — originally to an annual deficit of 3% of GDP and total debt of 60%.

Twenty-five years of heavy use have shown the Pact is often honoured more in the breach than the observance. But it still remains a principle of EU law that countries should try to restrain and reduce borrowing.

Finance ministers who bear the scars of battles around Brussels negotiating tables must be open-mouthed to see the EU’s behaviour now — and that of the European Commission in particular.

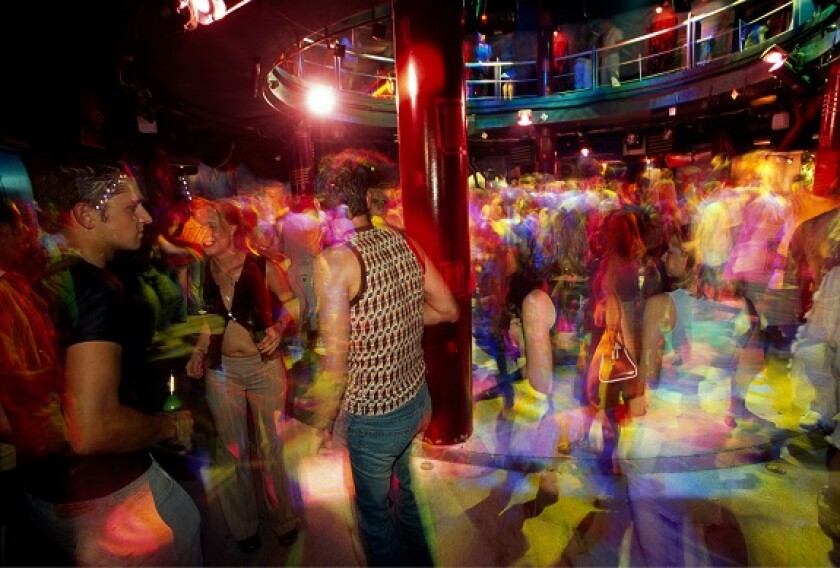

The virtuous schoolma’am has cast off her grey duffle coat and high collar and is doing the conga in a leopardskin leotard.

No sooner given the power to issue bonds at scale to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, the EC is now devising a scheme to finance Europe’s reaction to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with defence and energy spending.

How big could it get? Bankers have heard €100bn, €500bn, perhaps even more. ‘Who cares? It’s only debt’ appears to be the EC’s philosophy.

This is entirely understandable. The EU has been given the keys to the secret garden of debt, which it had never entered before. The wonderful attraction of being able to have things now and pay for them some other time has gripped it good and proper.

For the time being, the ventures are probably wise. Europe's needs at the moment are enormous, above all to deal with the humanitarian crisis in Ukraine and for the 2.1m refugees who have headed west.

The borrowing plans certainly seem popular. National governments want big spending to mitigate the effects of Russian aggression, just as they do for climate investments. Sharing the burden makes it so much more palatable — and means the sums will not appear in national debt figures.

At some point, Europe will have to decide how to service the debt. At that moment, the shine may come off, as countries argue even more intensely than before at Budget time about how money and costs are shared within the EU.

But one argument will never happen: how to repay the debt.

Not over centuries like most states, but in a handful of years, the EU is building a national debt. And as everyone knows, once created, a national debt — much like most other debts — is never paid off.