“Everything that has to do with mortgages and real estate investment leads to a stronger involvement of long term-oriented investors, so we see more insurance companies coming in — not only German ones, but on a European basis,” said Andreas Petrie, head of primary markets at Helaba in Frankfurt. “They are especially looking for long maturities, 10 years-plus.”

This week, Helaba is in the market with a 15 to 20 year deal for Hanova Wohnen, a housing company 90% owned by the city of Hanover and 10% by Sparkasse Hannover, a local savings bank.

Property companies are a large segment of most capital markets, but not the Schuldschein. The German promissory note market has two segments — one for public sector entities and one for private. The latter is dominated by German industrial companies, though it has internationalised extensively in recent years, first to Austrian issuers, and then to other European firms and a very few from Asia and emerging markets.

Yet Germany has a large property company sector, notably about 1,000 companies that own housing. Many of those were originally, or still are, owned by municipalities and industrial firms.

Some of those were sold from the 1990s, forming the basis of new listed companies such as Vonovia and Deutsche Wohnen.

The main obstacle to them using the Schuldschein market has not been a resistance from investors to taking on property exposure. As most of the investors are local savings and cooperative banks, they might be glad to diversify their exposure away from local property markets.

Rather, the problem has been the issue of security.

Security problems

It is difficult to structure a Schuldschein as a secured loan, because the market has no concept of a trustee, and Schuldschein deals, legally speaking, are bilateral loans. If there are 70 investors in a deal, each is making a bilateral loan to the borrower. There is no process for collective decision making among the lenders, so if security had to be enforced, it would be unclear who should do it, and on behalf of which lenders.

Property companies can issue unsecured debt in the Schuldschein market, but investors have not been attracted to it, because they do not want to be in a structurally subordinated position. Most property firms had extensive mortgage debt, which would have first claim over much of their assets if the company was struggling to service its debt.

Now, room for Schuldschein issuance is opening up, because property companies are moving more and more to unsecured funding.

There are many advantages. Using mortgages involves a lot of administrative work, such as legal fees and lodging charges with the land registry. It also makes it more cumbersome for property companies to manage their portfolios, for example by selling assets and buying others.

“There is a general trend to go away from mortgage-based funding to corporate, unsecured funding,” said Petrie. “They like the flexibility. Their LTVs are very low, so they have sufficient balance sheet capacity for new unsecured debt, so they are shifting to it in portions.”

Companies have been helped by rising property prices, reducing their indebtedness, relative to assets. German housing prices have been climbing steadily, with two brief interruptions, since 2010. For the last three years, the rate has been between 5% and 10% a year.

Into the Schuldschein

The big, listed housing companies have led the way in moving to unsecured debt, but smaller ones are following.

The Schuldschein trend began at the end of 2016, when Helaba, which owns its own housing company, GWH Immobilien, with 50,000 flats, brought it to the market for a €100m deal.

Normally, unsecured debt is significantly more expensive for property companies. But for some borrowers, that has turned out not to be the case.

“The [internal bank] ratings on their unsecured debt were so good, in the A- to triple-B region, that there is not a big difference in cost between corporate debt and mortgages,” Petrie said.

Fabian Lander, head of corporate finance and sustainability at Volkswagen Immobilien, confirms that. The company owns housing and provides property services to the VW group, such as building dealerships. "On our latest Schuldschein, the prices were inside the VW bond curve," said Lander. "If Schuldschein prices become tighter and secured loans have widened, then the gap has narrowed."

VW Immobilien is under the rating umbrella of Volkswagen. Some investors see it as VW risk, others as a separate, real estate-related credit. On its most recent Schuldschein deal in May, the five year tranche was priced at a 100bp credit spread, the 10 year at 150bp.

Lander said the pricing banks were offering on mortgages had widened since last year by about 10bp-15bp, for a loan with a typical loan-to-value ratio of 60%. The two instruments are difficult to compare — for one thing, mortgages usually amortise at 3% or 4% a year — but for a 10 year mortgage with a seven year average life the margin might now be 80bp. That is perhaps 40bp tighter than a seven year Schuldschein, based on VW Immo's curve.

Since the GWH deal, several more housing companies have come to the Schuldschein market, including Wiener Wohnen, which owns 220,000 flats for the city of Vienna. Neuland, a Wolfsburg housing company, and Hanova Wohnen of Hanover have also issued.

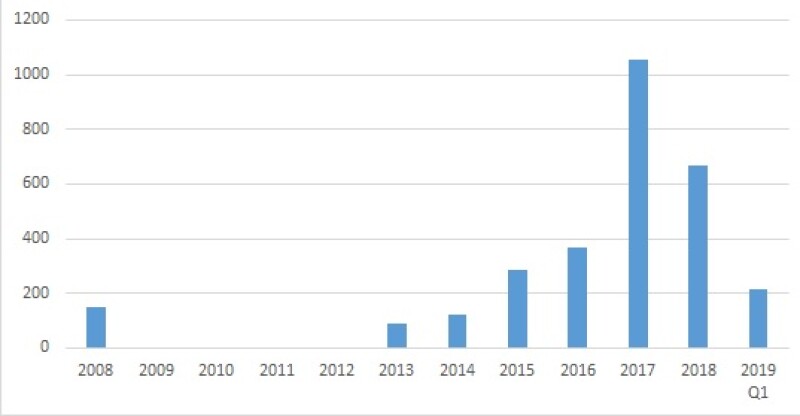

Helaba research shows that there were only three real estate Schuldschein issues between 2008 and 2014. But by 2017 the market had swelled to seven deals totalling €1.1bn and last year there were nine, for €670m. The issuers are a mixture of municipal and private sector, and of commercial and residential property.

These figures do not include the €1.3bn of Schuldscheine issued in recent years by Orpea, the French nursing homes group, which is classified in the healthcare sector.

Property company Schuldschein issuance (€m)

(source: Helaba Research)

Insurance appeal

Property companies, especially those in the stable business of owning housing estates for the long term, like long term debt. But the Schuldschein is mainly a medium term market, offering three to seven year maturities, and less frequently up to 10 years.

The private sector Schuldschein is in fact legally capped at 10 years, since the German civil code that underpins it gives the issuer a call right after 10 years, making it unattractive to investors. However, issuers wanting to borrow beyond 10 years can issue a Namensschuldverschreibung, which is equivalent to a Schuldschein.

Nevertheless, most of the bank investors do not lend for so long. Even in the secured loan market, banks would only lend up to 10 years, Lander said.

This obstacle, too, has been surmounted.

In recent years institutional investors, such as insurance companies, have found the Schuldschein market unattractive because interest rates have been so low. Banks only need to earn a credit spread, whereas institutions need to make a positive return for savers after inflation. Lending at 100bp-200bp over Euribor, when Euribor is close to zero, does not make them enough money.

But at longer maturities, base rates are still positive. The euro five year swap rate is now about -0.1%, but the 10 year is 0.3% and the 20 year 0.8%. Credit spreads are also higher on longer debt.

About five or six bigger German insurance companies still participate in the Schuldschein market, but very selectively. They take big tickets, so typically absorb about 6% to 9% of the issuance each year.

But the new, longer term property deals are helping draw institutions to the market. Smaller insurance companies, including some outside Germany, have been participating. Some banks also invest, but the demand is driven by institutions.

"From 10 years on, the investors are all institutions — insurance companies and pension funds," said Lander. VW Immo had tranches of five, seven, 10, 12 and 15 years on its first Schuldschein and five, 10 and 15 on its second. The investors were all German, apart from some Austrians in the first deal.

"To hit the Asian market you have to provide short term debt and variable rate, like for English investors," Lander said. "The Germans like fixed." VW Immo only issues fixed rate Schuldscheine.

Some of these insurance companies also provide bilateral mortgages out to 20 years.

Most of the housing Schuldscheine have covenants, partly to reassure investors that they will not be disadvantaged, compared with secured lenders. Typical covenants include total debt to assets, the ratio of unsecured debt to unencumbered assets and interest coverage.

Looking abroad

To an observer in the UK, the growth of Schuldschein issuance by German housing companies prompts the thought: would UK housing associations — another large sector, active in the capital markets — be interested in tapping this market?

So far, it has not happened. If banks try to pitch the idea, they may run into the same blockage that has all but stopped housing associations issuing unsecured bonds in the UK: they have so much secured debt that the structural subordination problem remains a real one.

However, other non-German property companies have gone to the Schuldschein market. Probably the most prominent is Orpea. It has used the market extensively and its €1.3bn of Schuldscheine now make up 26% of its net debt.

The rest is split between 20% in bonds (a €400m unrated public bond and €625m of Euro private placements), 36% bilateral bank loans and 18% finance leases. Of the total, 28% is secured, including all the leases and some of the bank loans.

Secured debt is cheaper, but Orpea does not mind paying a bit more to issue unsecured, because it brings flexibility.

“It’s always interesting to use different markets because you can widen your base of investors,” said Steve Grobet, investor relations director at Orpea. “It’s very surprising the development of the Schuldschein market we’ve seen over the last five or six years. The development has been very strong, with a wider and wider base of investors. At the beginning it was mostly German banks or managers. Now you have other European banks or asset managers and investors from outside Europe, mainly from Asia but also the Middle East and Latin America.” Asian insurance companies, as well as banks, had participated, he said.

The Schuldschein’s offer had lengthened in maturity, he added. Orpea has not yet issued Schuldscheine longer than 10 years. It would be interested in doing so, but has not yet received any proposals.