On September 4 Mauritius got the news it had been hoping for: a committee advising India’s government suggested that a planned new piece of legislation designed to crack down on tax evasion be delayed by three years.

The suggestion, which followed several rounds of protracted bargaining between the lawmakers of both countries, was a huge relief for Mauritius. It accounts for roughly 45% of the foreign direct investment (FDI) that goes into India, largely as a consequence of a double taxation treaty between the two that allows companies based in Mauritius to use its tax rates when investing into India.

New Delhi wanted to introduce the new rules to tighten up on what it perceived to be companies attempting to invest in India while trying to avoid paying its tax rates. As the prime originator of FDI into the country, Mauritius stood to be particularly affected by any tightening of the rules.

The wrangling and uncertainty that surrounds the Mauritius-I ndia double taxation treaty in some ways plays to the heart of what Mauritius is trying to become. It has long promoted itself as a low tax investment centre, primarily to India but increasingly to countries in Africa and further afield too. To help facilitate this the island has signed 36 double taxation treaties, which allow companies operating from Mauritius to be taxed at rates equivalent to the island’s standards, even if the rates of the countries that they are investing into are far higher.

Given that Mauritius possesses low corporate and income taxes, it has quickly become a favoured centre for companies seeking entry into the countries with which it has taxation treaties. Local officials and bankers are quick to proclaim the fact that Chinese telecom company Huawei Technologies decided to set up its Indian Ocean and sub-Saharan African headquarters in Mauritius in 2006, that Swiss food retailer Nestlé has an office on the island, and that other companies are also considering such opportunities.

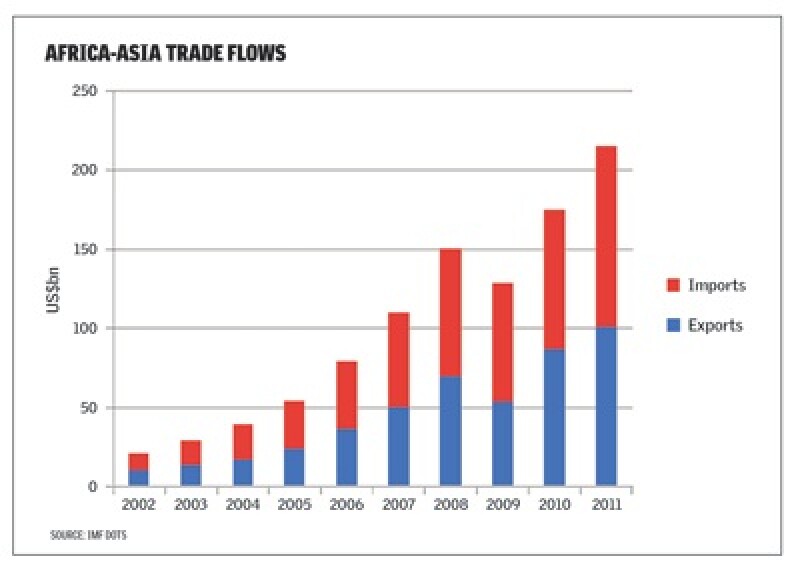

For these participants in Mauritius the future looks promising. Local companies expect that many more investors will follow, attracted by the potential and by the opportunities available in the continent to the west. Increasingly, they argue, many of these investors may come from Asia.

“Myanmar is just becoming investible and so is Africa. People in Asia have developed a nuanced view of risks and opportunities, the times to make risks and the time to pull back, and now it’s clearly the former for Africa,” says James Benoit, chief executive officer (CEO) of Afrasia Bank, a Mauritius-headquartered institution seeking to work with investors into African countries.

The centre of Mauritius’s appeal may be the tax rates it offers, but it supplements these with several other factors, not least of which are a balmy climate, liberal and increasingly international class financial laws, and a largely bi-lingual and well-educated population.

But the country is not the only one vying to be the investment hub for law firms, accountants, hedge funds, resources companies and retailers. Many view Africa as the last place in the world for multiple emerging market opportunities, and other nations are scrambling to attract the investors planning to take advantage of this.

Mauritius enjoys some advantages, but it cannot afford to be complacent as it seeks to become Africa’s financial and services gateway.

Evolving economy

Mauritius was once best-known as a sugar cane exporter, but the island began to develop light manufacturing and tourism in the 1980s, and shortly afterwards began developing its banking and the financial markets.

The drive to diversify the economy was in part the product of a successful free education drive in the decade, which had led to large numbers of young people in need of jobs. Many of its best and brightest had gone abroad seeking work as a result, and the government realised that it was losing an important opportunity to develop the country.

Banking was not a new sector to Mauritius – the island has had a banking system for 175 years, and by the 1980s there were five banks focused on servicing the local populace. But Mauritius’s government decided to add offshore banking licences to this, along with developing its capital markets. In 1987 the country set up its stock exchange, while in 1989 the first offshore bank licence was awarded. Then in 1992 the first non-banking services licences were issued, allowing for the development of a fund industry and investment holding companies.

At the same time as the island began expanding its banking sector it also sought to sign more taxation treaties with other nations.

These treaties are appealing because Mauritius’s taxation rates are so low. The Income Tax Act of 1995 stipulated Mauritius’s corporate tax rate at only 15%, with income tax rates enjoying an average 15% too. Added to this, dividends paid by locally-listed companies are tax-exempt, and Mauritius has no capital gains tax.

Furthermore the country is a part of Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, both of which offer tax invectives for trade with other members.

That’s not all. “Mauritius also offers investment and protection agreements,” says Rama Sithanen, former minister of finance and now chairman of International Financial Services, a corporate consultancy firm. “For example the government has signed many agreements regarding the protection against expropriation of assets, so that foreign investors won’t be discriminated against, and agreements about access to foreign exchange, to give companies flexibility to repatriate profits and income.”

These agreements have made for some compelling rules for more companies to consider setting up on the island, which dovetailed well with Mauritius opening up its bank and non-banking sectors.

The two decades since have seen increased reform and development, including in 2004 an overhaul of the banking act to allow banks to conduct offshore and onshore banking under a single licence. The result has been that from five banks in 1987 Mauritius now plays host to 20, and Aisha Timol, CEO of the Mauritius Bankers Association says that more could arrive.

“We’ve had interest from a number of banks in setting up here, although of course they have to apply with the central bank,” she says.

The country is increasingly playing host to asset management companies, investment advisers and private banks, too, all seeking to take advantage of the island’s relatively low tax rates and its appealing location off the coast of Africa, yet also relatively near to the Middle East and India.

“Mauritius may be a four to five hour flight from most places, but in reality that covers many locations, from Dubai to Mumbai, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Johannesburg and Nairobi,” says Benoit.

The result is that Mauritius’s financial sector has grown to encompass around 15% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), which grew at 4.1% in 2011. This makes the financial sector the second-largest contributor to the economy after tourism, versus being seventh back in the 1980s. If Mauritius is to keep enjoying healthy economic expansion, it needs to keep adding to the appeal of this industry.

Taxation portents

India has been a particular recipient of such Mauritius-sourced investment flows, with approximately 45% of its FDI being sourced from Mauritian companies, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers.

The sizeable flows of investment into India are largely welcomed, but New Delhi has become increasingly suspicious over the past decade that local Indian companies have set up operations in Mauritius in order to round-trip, or invest back into the home country purely to cut their rates of taxation.

This has become an increasingly contentious issue for the Indian government, which has become increasingly threatened by accusations of cronyism and inertia over the past three years. New Delhi’s rhetoric about tax evaders has risen appropriately, in order for it to be seen to be doing something about them.

Worries in Mauritius had been growing that India could sacrifice the mutually beneficial tax relationship between the two purely for political concerns at home.

It was with some relief therefore that a committee appointed by New Delhi to research the viability of the double taxation agreement between the two countries in the summer came to the conclusion that it should be left alone, at least for now.

The decision relates to the General Anti Avoidance Rule (GAAR), which was introduced into India’s Income Tax Act this year. According to KPMG, GAAR can be applied to tax arrangements that are regarded as “impermissible avoidance arrangements” and allows the country’s tax authorities to designate existing relationships as such if necessary.

In other words, India’s tax authority could pursue investments from Mauritius for local tax rates, despite the double taxation treaty between the two nations, if it believed these investments were being conducted from Mauritius purely to avoid India’s taxes.

It’s a complicated part of law, and India’s prime minister Manmohan Singh created an expert committee to consider how best to implement GAAR. It submitted a report on September 1 which included recommendations to be made for amendments in the act (see box on page 64).

The recommendations are largely good news for Mauritius. The committee recommended that GAAR’s introduction be postponed by three years, citing the need for tax officers to be intensively trained to understand its ramifications. It also suggested that companies approved to be incorporated in Mauritius by the island’s tax authority should not have their residence questioned by India.

The committee will offer its final report on GAAR on September 30. However given the committee’s recommendations of delay, hopes are riding high that the double taxation treaty between Mauritius and India will not be heavily affected. The island’s largest source of investment outflows looks secure.

Asia into Africa

There is another reason why India’s tax authority might be reluctant to interfere too much with the double taxation treaty between the two nations: companies from India are increasingly seeking to invest into Africa, and they are equally willing to use Mauritius as a hub from which to do so.

The Mauritian government is certainly keen to encourage investors to direct their money into Africa via the island, and two of the increasingly most active sources of such fund flows are China and India.

China has for several years been raising its investments into Africa, largely as part of a drive to gain resources that it needs. Indian companies, meanwhile, seem to regard Africa as an appealing customer base. For example, Indian company Bharti’s US$10.7 billion acquisition of most the African assets of Kuwait’s Zain on March 30, 2011 was conducted via a Mauritian subsidiary company. Equally, when Indian conglomerate Essar purchased mines in Zimbabwe, it structured the deal via Mauritius.

The hope is that such flows will increase, particularly given the fact that the price of assets across much of Asia have been rising across the past decade.

“This is a generational opportunity,” says Benoit. “You can still make money in a lot of parts of Asia, but prices there are rising; if you look at property cycles in Hong Kong for example, they are back to 1997 levels. Whereas Africa is by any standards cheap.”

He offers bank valuations as one example, noting that African institutions can still be purchased for less than two times price-to-book value; a level hard to achieve in Asia. By comparison China’s Citic Securities has bought CLSA in its entirety for 2.2 times its likely book value, which most onlookers consider an expensive valuation.

“You might have to hold [African bank assets] for a while but you won’t ever see such cheap valuations again,” says Benoit.

Of course Africa remains a risky place to do business. The rule of law is uncertain at best in many countries, corruption is rife, and infrastructure often lacking. But the growth potential is huge.

According to the World Economic Forum in May African countries were six of the top 10 fastest-growing economies over the past decade. Fifty-two percent of the continent’s almost one billion population are urbanised, and this should rise to 58% by 2025.

The prospect of gaining access to relatively cheap resources, companies and the continent’s expanding middle class is an appealing one.

Mauritius certainly boasts some advantages as a base for those prepared to risk their money in Africa; a healthy rule of law, a population of bi-lingual or even tri-lingual people, most of whom speak English and French, the two business languages of Africa, and decent infrastructure.

“Mauritius is a bit like Africa with training wheels,” says Benoit. “It’s very culturally diverse, with Chinese, India, African and European people living here, which makes an adjustment for families easier.”

The island’s growth as a financial and outsourcing hub plays well into this, as Mauritius is beginning to gain the critical mass of accountants, financial consultants and information technology support to help a company cover multiple African countries from one location.

The signs are certainly positive. Local bankers say that every month they see multiple private equity funds or corporates interested in raising or investing funds into Africa via Mauritius. One estimates that he has spoken to 10 in the past three months alone, each interested in raising or investing US$300 million-US$400 million apiece.

The country’s efforts to stay at the forefront of regulatory change is helping its ambitions, too. In late 2011 the International Swaps and Dealers Association (Isda) officially extended its legal opinion to cover Mauritius’s updated legislation for derivatives, making it only the second after South Africa to have such a status in Africa. This market, while still nascent, will greatly help entice international companies to base operations on the island.

“Mauritius being approved by Isda helps when it comes to foreign exchange derivatives and hedging. From our perspective corporate operating in the region, whether European or African or Asian, are increasingly looking to house themselves in Mauritius to manage their regional treasury activity,” says Sridhar Nagarajan, CEO of Standard Chartered in Mauritius.

Of course, Mauritius is not the only country to have ascertained the potential of directing the steadily increasing investment flows into Africa. South Africa’s Johannesburg is equally keen to establish itself as the primary financial hub for the continent. Meanwhile Nairobi in Kenya wants to become an information technology and software centre, and combine this with related areas such as business process outsourcing, another sector in which Mauritius is trying to develop itself.

“There’s no doubt that Mauritius cannot become complacent,” says Timol of the Mauritius Bankers Association. “It has to keep expanding its services and improving if it is to remain at the centre of people’s thoughts when it comes to investing into Africa.”

But locals are quick to note that while the likes of South Africa boast far larger banking economies and equally developed financial sectors, the small size of Mauritius and its deliberate focus on attracting international capital has worked in its favour.

“South Africa is a big and developed country with a large local economy, whereas Mauritius’s local economy is only around US$10 billion, yet it has around US$180 billion of money flowing through the country a year,” says StanChart’s Nagarajan. “It’s naturally developed as an internationally focused economy that can support major international capital flows.”

However the country’s small size means that it cannot be all things to all men. “We are a small country so we need to be niche,” says Sithanen. “We have to identify countries and where we already have trade and economic relationships to cooperate with and act as an investment conduit to.”

He notes that this generally means eastern and southern Africa, the areas in which Mauritius has many trade agreements and is a member of economic associations.

“Secondly, we can’t participate in all sectors. We have to build some where we have a key advantage,” continues Sithanen. “Tourism, real estate, finance and outsourcing are all good examples, and areas where we are leveraging our competitive advantages.”

He adds that other opportunities exist in acting as a base for resources companies, consumer services, agriculture, telecoms and small and medium enterprises looking to grow in Africa. “There are low hanging fruits where we can build our expertise and share these skills with African countries that are interested.”

He feels that Mauritius could potentially increase its financial services contribution to the economy from 15% to 30% in five years if it does a good job.

Part of this process involves marketing the country’s strengths; something that it is working hard to do. Observers say that Mauritius’s vice prime minister and minister of finance Xavier-Luc Duval (who was unable to respond to requests for an interview by press time) is driving efforts to promote the country internationally, especially in Asia. Additionally the island hosted the 3rd World Chinese Conference from September 6-9, which focused on China's growing diasporas in the world.

The island is also welcoming governmental links. China in particular is raising its investment into Mauritius. On July 5 Duval and China’s vice minister of commerce, Chen Jian, signed documents that allocated Mauritius a grant of MUR270 million (US$8.8 million) from China to invest into various development projects, as well as discussing improved trade and FDI links. The Export-Import Bank of China is already funding the island’s Bagtelle Dam project with favourable loans.

Transportation and education

Mauritius’s desire to attract attention from the world at large is wise, because for all its advantages it’s not a perfect investment hub into Africa.

The island may be considered part of the African continent by international agencies, but there’s no getting away from the fact that it is 2,000 kilometers away from Africa itself. Several Mauritius-based professionals told Asiamoney that the most vulnerable point of Mauritius’s sales pitch as Africa’s financial hub is its transportation network.

It’s a particular sensitivity when it comes to flights from Asia. Mauritius Air offers limited direct flight channels from Asia, with travel hubs such as Hong Kong only having one flight a day. Air Emirates offers another option, but it routes through Dubai, which adds many hours to the flight time.

“It’s important to get the air routes right if Mauritius wants to attract more businesses and expats to settle here,” says one senior banker working on the island. “Right now it can take a long time to get here from Singapore or Hong Kong, while it takes almost a day to get into Dar es Salaam [capital of Tanzania] or Harare [capital of Zimbabwe]. There’s an opportunity cost to doing such trips.”

It’s an issue that the government understands needs to be improved. The airport in Mauritius is undergoing a thorough overhaul. But flights that are both more regular and more direct will be needed to entice more businesses to set up permanent shop on the island.

Education is another point that Mauritius may need to work on. General feedback about the quality of schooling was that it is a very good standard up until high school, but that it is not up to international class above this point. As a result most affluent locals and expatriates send their children abroad to be educated and many decide to stay there to begin their careers, making it tougher to entice them back. This also needs to change.

In fairness the government knows this; one official notes that the UK’s University of Middlesex has been encouraged to open a campus, as has India’s Institute of Technology in New Delhi . But more are needed. Get the likes of Harvard, Oxford or Edinburgh to establish a campus to cover Africa and Mauritius would have a much greater selling point as an education hub, which would dovetail nicely with its desire to entice more international companies, expats and their families to live on the island.

As things stand, Mauritian businesses are gambling that the quality and safety of daily living on the island will make up for the extra travelling requirements. They also believe that being based off of the eastern coast of Africa makes the island a good centre for the rising sums of Asian capital they foresee seeking a home in Africa.

In this they may be correct.