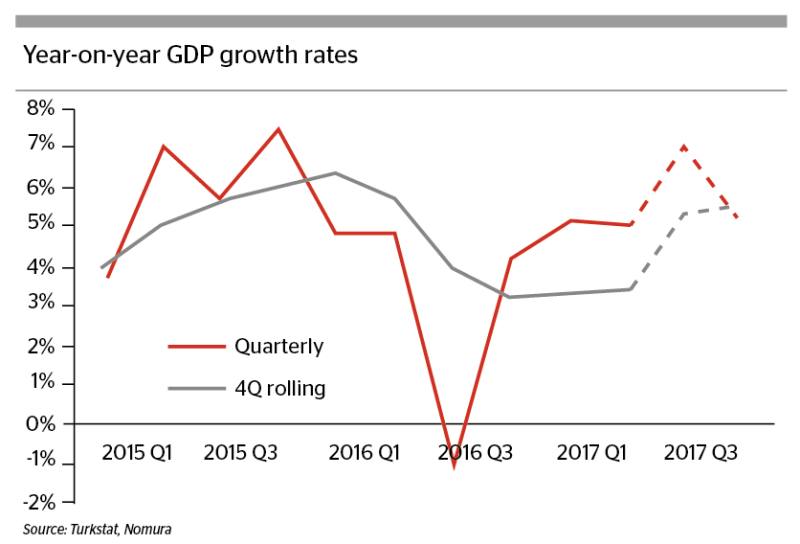

Turkey’s Statistical Institute reported second quarter GDP growth of 5.1%, down marginally from the 5.2% recorded in Q1 this year. However, this marks an impressive increase on the 0.8% quarter on quarter contraction recorded in Q3 2016.

A return to strong growth, driven by the government’s fiscal and credit stimulus this year, also provides a useful political tool for president Recep Tayyip Erdogan and is an apparent validation of the April 16 vote to increase his executive powers.

However, any hopes that Erdogan would turn his attention to reform have not yet been realised.

“Strong growth is not due to any reforms implemented since the referendum, but is being driven by domestic demand on the back of credit growth and government spending,” says Inan Demir, an EM economist at Nomura in London.

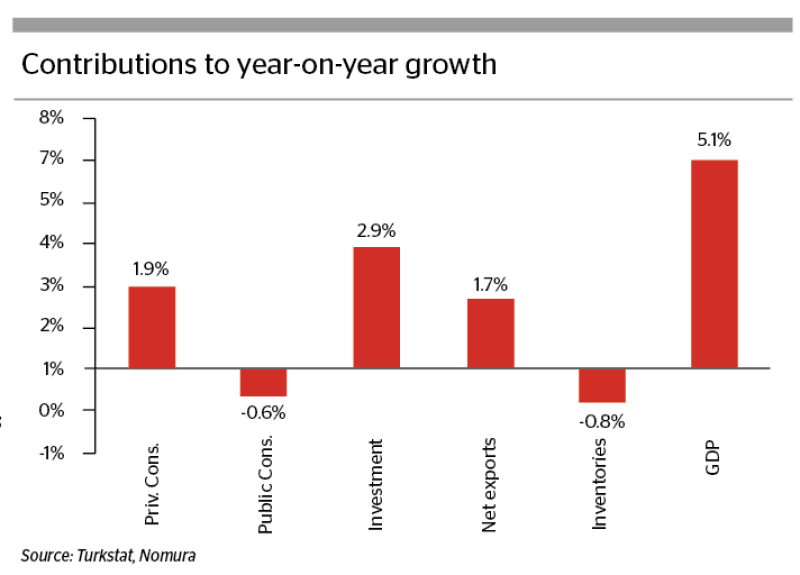

Investment spending, particularly in construction, and net exports were the biggest contributors to the headline year-on-year growth rate.

Demir expects growth to accelerate again in Q3 because of the low Q3 2016 numbers (0.8%) and because of continuing fiscal and credit splurges. Turkish GDP should grow 5.5% in Q3, but drop off to 3% next year, he says.

The domestic demand that Demir refers to comes from the surge in credit growth in Turkish small and medium term enterprises this year.

Turkey’s credit guarantee fund (KGF) offers partial guarantees on bank loans to small and medium term enterprises in Turkey. Though established in 1993, the KGF was used only marginally until this year when the government made available some TL250bn ($70.1bn). Already TL210bn of the fund has been used.

Household final consumption expenditure has officially increased by 3.2% compared to Q2 2016.

‘Are you kidding?’

But not all are convinced that Turkey’s success is entirely plausible. In a note published on September 12 titled Turkey: Are you kidding me? Commerzbank analyst Lutz Karpowitz took aim at Turkey’s statistical institute, doubting the government’s use of “more than questionable” data.

Kaporwitz wrote that a 2.1% quarter-on-quarter rise suggests the Turkish economy recorded “the fastest growth amount of all countries globally in Q2”, a claim, which he believes, shows the data to be “politically influenced”.

He questions the government’s claims of an investment boom, suggesting that international data show otherwise. “Foreign direct investment in Turkey fell by 29.9% to $13.2bn in 2016, with no sign of a trend reversal in the first half of 2017,” he wrote. “Instead another 8% fall to $4.9bn was recorded.”

Kaporwitz argues why the apparent rebounds in Turkish tourism and household consumption do not add up either. Feedback has been positive, he says, and while he doesn’t know if his clients have acted on the report by slowing investments into Turkey, it does feed into a broader narrative of mistrust and scepticism.

Trust issue

Any erosion of international trust is exactly what Turkey should be working to avoid, particularly if its recent credit-fuelled measures to promote growth are unsustainable in the long-term, says Mohieddine Kronfol, chief investment officer, global sukuk and MENA fixed income at Franklin Templeton in Dubai.

Although Turkey has a very manageable fiscal deficit — which looks set to widen to 2% of GDP this year — and has reduced its debt-to-GDP to 29% in 2016, with primary surpluses averaging 0.7% of GDP from 2010 to 2016, analysts agree that the government cannot maintain its measures to stimulate growth.

Turkey continues to run a current account deficit, and is vulnerable due to a strong reliance on non-resident investor sentiment.

“The current account deficit contributes to an elevated external funding need of 25% of GDP in 2017, which will remain at a similar level in 2018, reflecting maturing private external debt,” said a report by Scope Ratings on September 22. Scope rates Turkey BB+.

“The more important question is what their trajectory of growth is?” Kronfol adds. “Investors are as divided as voters are. Some believe the government will concentrate on reforms, and stimulate the economy while others are warning that you have a continuous erosion of institutional ability to implement reform”

However, he is not so sceptical of Turkey’s growth numbers, noting that the country’s balance sheet is able to support the government’s fiscal stance, over the medium term.

“Growth of 4% is something they can achieve,” he says. “They haven’t really been challenged on fiscal deficits or debt levels, that isn’t a major issue.”

What is important in the long term, he says, is that the government addresses the structural issues needed to attract long term foreign direct investment, and goes about this in an open and transparent way.

“In Turkey there is arguably too much focus on politics and on the presidency, but they almost need to go back to basics, to ensure that the protection of private capital and attracting investments remains a priority,” he says.

Structural reform has been on the agenda for Erdogan’s government for many years, but regularly takes a backseat to international affairs or election campaigning. It was hoped that, following April’s constitutional referendum, reform would once again be a priority.

Until this happens, Kronfol says, Turkey will remain vulnerable to flighty investor sentiment towards risk assets and emerging markets more broadly, as well international oil prices.

Murky SWF

But investors warn that despite attractive growth, Turkey’s poor transparency hinders its ability to attract foreign investment.

For Markus Schneider, senior emerging markets economist at AllianceBernstein, Turkey’s GDP figures are less important than macro headline indicators and credit data. In particular, he is concerned about the potential for off-balance sheet borrowing by entitites in the government’s sovereign wealth fund, the Turkey Wealth Fund.

In August 2016, a law was passed mandating the establishment of the fund for which the government set an initial target of $200bn, amounting to around 28% of Turkey’s 2015 GDP, as noted by law firm White & Case.

Many countries run respected and successful sovereign wealth funds. While the Turkish fund’s stated aim is to invest in infrastructure — funding for which is much needed — investors are sceptical.

The fund owns many key public assets, which it has said it plans to use to grow and stabilise the Turkish economy. Those assets, including a 100% stake in Ziraat Bank, and a 51.1% stake in Halkbank, may now be used as collateral for Turkey’s major infrastructure projects.

“It is not really like a traditional fund like those in the Middle East,” says Schneider. “They have limited accumulated savings and there is some uncertainty about how it would work.

“What is more disconcerting is if the government uses the fund for significant off-balance sheet quasi-fiscal spending,” he adds. “At least with the credit guarantee fund and current fiscal spending, we understand what is going on, but the sovereign wealth fund could accumulate debt which will be more difficult to monitor.”

Gregorio Saichin, global head of emerging markets fixed income at Allianz Global Investors calls the fund a “black box”.

“Investors don’t like black boxes,” he says. “I haven’t seen the final charter so I’m not sure what it’s supposed to do, but off-balance sheet funding is not good. It diminishes transparency. We know the government is in deficit already, so why do they need to create such an entity?”

Vote worries

Another concern for investors is the possibility that Erdogan will call an early election. The next Turkish presidential election is set for November 3, 2019 but there is a strong possibility that it could be brought forward, says Demir at Nomura.

“The possibility of early elections should be considered strongly, despite all of the government officials speaking out against this,” he says.

“I’m sceptical about the sustainability of growth until 2019. A lot could happen to derail it and the domestic political scene is changing.”

Demir points to the recent resignation of Istanbul’s long serving mayor Kadir Topbaş as evidence of increasing disagreements within the governing Justice and Development Party. Support for the opposition Republican People’s Party is around 20%, and it has held large scale public demonstrations. Demir believes Erdogan will call elections before that support strengthens.

AllianceBernstein’s Schneider agrees. “We are constructive on Turkey but it all boils down to whether they will have early elections or not, that is the main concern. Erdogan is trying to stimulate the economy so that he creates a feel-good factor to try and win the election.”