Many of Asia’s governments are under financial pressure. Pakistan, for instance, received approval from the International Monetary Fund in July for a loan that would help it stave off a debt default.

Sri Lanka, meanwhile, has abandoned payments on all international debt amid an escalating political and economic crisis that saw protestors take to the streets and its president take to the skies as he fled the country. It has already defaulted on its international debt.

In Maldives, a tourism-reliant island country that was battered by the Covid-19 pandemic, the economy shrunk by 33.5% in 2020 from growth of 6.9% the previous year, before rebounding to 31.6% in 2021. It is expected to grow by 11% this year, and 12% in 2023, according to research by the Asian Development Bank.

Laos is also in trouble. Growth has been crippled due to the health crisis, the government’s foreign exchange reserves have tumbled, and its international credit ratings have come under pressure due to its long-standing reliance on debt.

With overall debt raising conditions in Asia bleak — due to a combination of rising dollar interest rates, volatility driven by fears of global recession and geopolitical tensions — it’s unlikely any of these countries' ministries of finance will be able to turn to the bond market at a price they can digest.

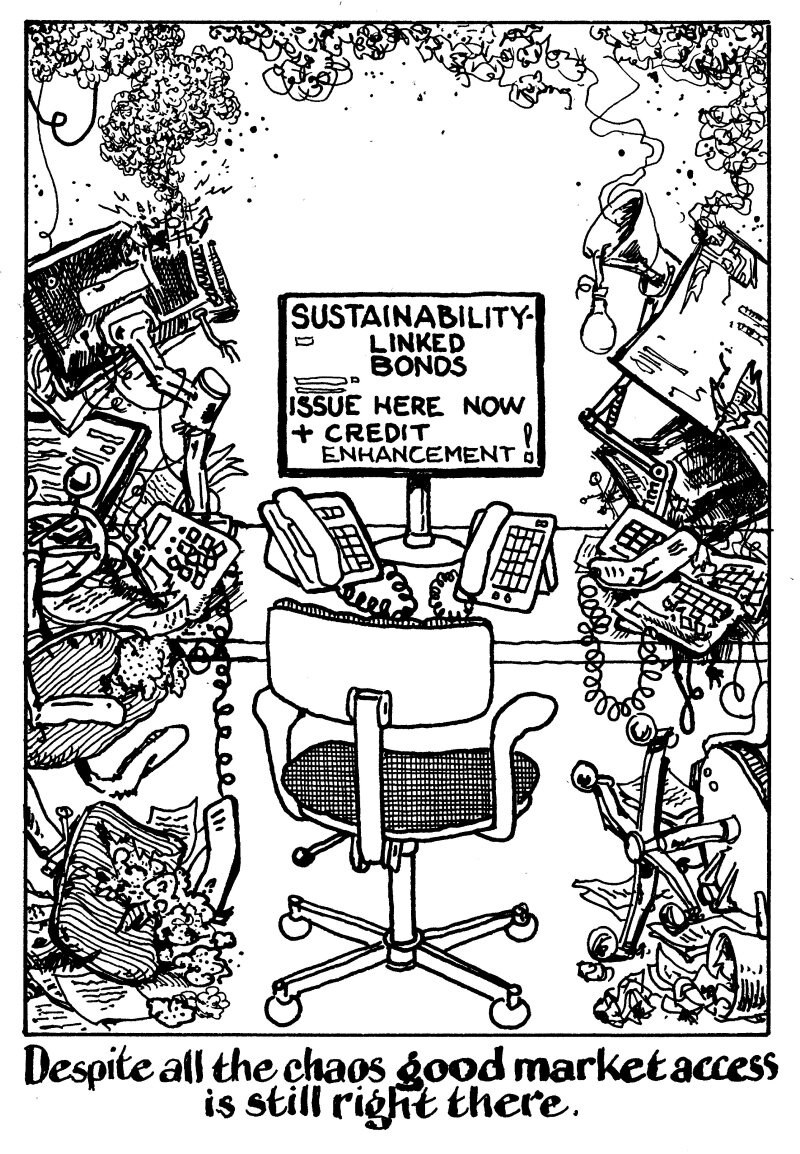

Under the circumstances, it’s time the beleaguered sovereigns look closely at sustainability-linked bonds, possibly with credit enhancements, to tide themselves over.

The potential is there. Both Sri Lanka and Maldives, as examples, are island nations constantly under threat from rising water levels due to climate change. Additionally, Maldives generates about 860 metric tonnes of waste every day, most of which is burnt in the open, creating a health hazard for the public and for its marine life.

Laos’s growth has long been fuelled by its reliance on natural resources, meaning it is in dire need of an economic model that will help reduce poverty, conserve its environment, and strengthen resilience to natural disasters and economic shock. Pakistan too needs to turn its focus on clean water availability, as well as on social elements like lifting millions of people from poverty.

Therefore, there are plenty of sustainability problems that these countries could build meaningful performance targets around, that ESG-dedicated funds would crowd around, while not hobbling themselves to dedicating the use of proceeds as with green bonds.

Adding credit support from development finance institutions or multilateral development banks would turbo charge the offer.

Belize’s blue bond from November 2021 offers a precedent. Last year, the coastal country used the Nature Conservancy’s blue bonds for ocean conservation programme to fund a buy-back of its $526.6m 2034 bond.

The US government’s Development Finance Corporation provided political risk insurance, increasing the credit quality and reducing the cost of the blue bond for Belize. The debt restructuring helped Belize reduce its debt, while parking some of the funds raised for its climate and ocean conservation efforts.

Such structured deals can be replicated in Asia. Maldives raised $500m in total from the international bond market in 2021 through three transactions. It managed to get away with a single digit coupon of 9.875%. But those levels are unachievable now, unless Maldives manages to tack on an ESG label and brings on board an international development financial institution.

The same goes for Sri Lanka. GlobalCapital Asia understands the ministry of finance had mulled a possible blue bond, with a partial guarantee from the World Bank, last year to refinance debt.

But tough pricing asks from Sri Lanka, as well as its demand for new money, foiled the fundraising, with the country eventually ending up in a political crisis this year.

Stressed governments in Asia should not lose any time. Given choppy funding conditions, multilateral support will still help sovereigns save on funding costs on their bonds. A sustainability linker would also draw interest from global development banks, something a plain vanilla bond will not do.

With global markets in the state they are in, an aggressive pricing or structure stance will lead nowhere. Instead, embracing the global sustainability agenda and leaning on credit enhancements could very well help cash-strapped governments out of a tricky spot.