Sustainability accounting is coming. Fulfilling the hopes of progressives over many decades, companies and other organisations will have to report on their environmental and social impacts as part of their official, audited accounts.

The process has taken a long time, and it will not be quick from here on either — accounting reform is a complex business that requires many stakeholders to agree and much education of users.

But the momentum is now inexorable. Last November at Cop 26, the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation, which oversees international accounting standards, set up the International Sustainability Standards Board to write the rules for this new era.

At the end of March, the ISSB published drafts of its first two standards for a four month consultation: IFRS S1, covering general disclosures, and IFRS S2, on climate disclosures.

Many of the most influential groups in global finance, such as the Taskforce on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures and the World Economic Forum, have already fed their ideas into the process and will bless its output.

All agree that capital markets badly need official standards, to enable investors to compare issuers’ environmental and social performance fairly.

Many have drawn the analogy with the emergence of formal financial accounting rules a century ago.

What has not been fully appreciated is what will be required to make these standards robust.

The main effort at the moment is on writing the standards — but arguably more important is how they are enforced.

Financial accounts are about money. Money is either where it is supposed to be, or isn’t. Auditors are supposed to check this, by comparing sets of records held by lenders and borrowers, customers and suppliers, banks and depositors.

The accounting profession has blemishes on its record, from Enron to Wirecard. But no human enterprise is perfect, and auditors at least have the right tools and training for the job.

In severe cases, regulators and the police can investigate crimes.

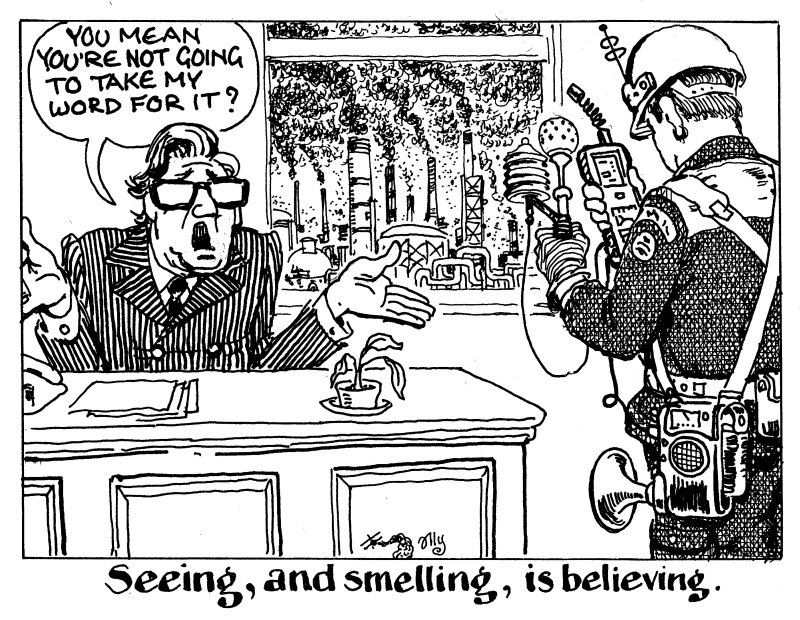

But when corporate disclosures are about carbon dioxide, use of scarce water resources, ships discharging chemicals at sea or child labour on cocoa farms, how are PwC, Deloitte and their ilk going to check companies’ claims?

Hard hats and clipboards

Up to now, companies have largely been able to self-report their environmental and social data. If they get caught lying, it would of course be hugely embarrassing, and fraud charges could be brought, since they had misled investors. So the incentive structure is not bad.

But there is no systematic process for checking claims. When abuses crop up, the whistleblowers are usually NGOs, journalists and private citizens. Bringing offenders to any kind of justice often takes years.

If sustainability metrics are included in official accounts, investors will expect and believe that they are more reliable than the figures they are used to reading in corporate sustainability reports. Not that these are lies, but investors do not accord them the same credence as a P&L account.

That means this new reporting has to be done at a higher level of proof and verification than is applied to sustainability reports, or the result will be to fool investors with a false sense of security.

It cannot be tolerated for companies to simply report their own figures, and accountants check them superficially, trusting the information supplied by the business.

Sustainability disclosures are not about money, but real people, events, processes and substances in the physical world. The truth of these can only be checked by people in boots and hard hats, with the right sensors and expert knowledge.

A whole profession will be required, of environmental and social auditors. These exist already of course — environmental audits have been around since the 1980s. But the industry is not nearly big enough yet to cope with the huge task ahead of it.

The most credible firms to enter the space and lead it are organisations such as DNV, Bureau Veritas and Eurofins, which already offer a huge variety of technical verification and testing services for every industry with health and risk issues, from food and medicines to energy and aviation.

These companies’ businesses are founded on helping companies fulfil their legal requirements to produce checks and reports, above all for safety reasons.

This could be Rotterdam or anywhere

Sustainability reporting will produce a mountain of new mandatory reports — but without the same statutory backing and safety consciousness. Who is going to check that beef sold at McDonald’s in Texas does not come from deforested patches of the Amazon?

The need is particularly acute, since the biggest risks do not come from outright lying but from weak and unrigorous application of environmental science, or poor verification on issues like human rights.

Last week an investigation in Rotterdam using infrared cameras showed methane — a greenhouse gas 80 times more powerful than carbon dioxide — escaping from ships powered by liquefied natural gas.

LNG is a cutting edge technology the shipping industry sees as its route to a greener future. Several sustainable financings have been raised on the basis of this.

If the shipping industry fills in its sustainable accounts using standard benchmarks and estimates for likely emissions, a false picture could be given.

The Rotterdam investigation, incidentally, was by an NGO, Transport & Environment.

Only physical monitoring can verify real performance.

And as Volkswagen showed with its Dieselgate scandal in 2015, even detection equipment can be gamed.

When it comes to large gas and petrochemical companies reporting their fugitive emissions, it will matter not just whether they have sensors, but exactly where they are located.

Or take the wood now increasingly being burned to generate energy, likely with worse overall emissions than coal but often booked as green. Even the official standards are not fit for purpose in this area.

No one should be under any illusion that financial markets will sort this out through investor pressure. The instinct of most in financial circles will be to accept shallow compliance. As long as all the boxes are ticked, people will want to get on with the deal. Quite understandably, eyes will glaze over as soon as boffins start talking about milligrams and microsieverts.

The risk, therefore, is one more huge and very expensive greenwash.

Can it be avoided? Yes. Governments need to mandate scientific checks of social and environmental reporting claims. This will require the creation of a new host of verifiers.

The front line can be private sector organisations — and, regrettably, but realistically — they are likely to be paid by the checked companies, creating the same conflicts of interest as accountancy suffers from.

But as long as the profession has the right statutory backing and oversight, this can be lived with.

There will have to be second and third lines of defence too, to deal with abuses. Regulators will be needed, but also environmentally qualified investigators — arguably a new force — with powers to arrest.

If all this sounds alarmist and draconian, consider that states already bring their full might to bear to prevent financial crime — which, at its worst, costs people money.

Environmental and social wrongdoing is far more complicated and difficult to trace, and the effects can be far more serious. Bring on the green police.