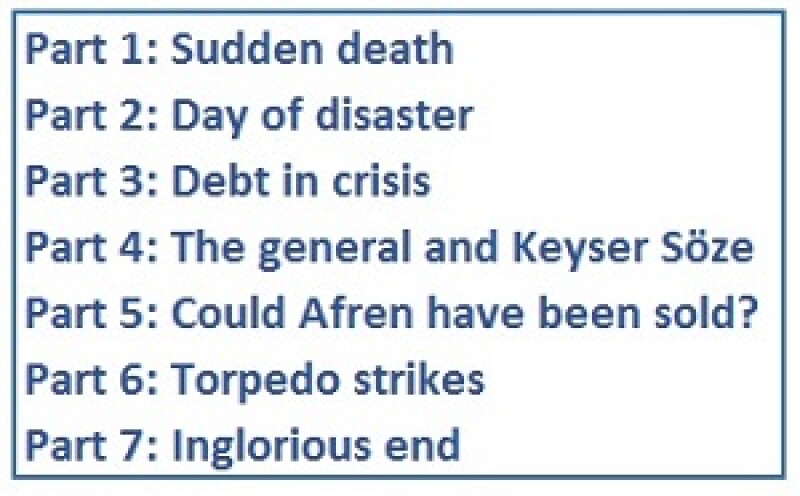

[Part 5: Could Afren have been sold?] | [Back to main page]

The reference to the March figures — 2015 full year net production guidance of between 29,000 and 36,000 barrels of oil a day — was surprising, as Afren had already, in its 2014 annual results released on April 30, reduced its forecast to between 23,000 and 32,000 barrels.

But the figures produced in July were even lower than the April ones, and according to two sources close to the restructuring, production was going to remain drastically low for at least another two years.

The figures have not been made public — one investor said they were subject to non-disclosure agreements. But in the words of one creditor, they were “really bad”.

One investor was furious that as late as June 22, Afren was still sticking to the April production forecasts, which a few weeks later proved so drastically wrong.

The July 15 announcement was shattering. It meant the whole restructuring had been built on shaky foundations.

The creditors had always expected Afren to need more money in July. That was why Afren was to have issued a $321m high yield bond that month as part of the restructuring agreement. But no one had expected it to need so much money.

Trading of Afren shares in London was suspended that same day.

The past few months had been nerve-racking for those involved. Several Afren executives in London received threats to themselves and their families and sometimes had to be escorted by company security outside the office.

But since April 30, when the restructuring deal had been signed, the problems had seemed straightforward, and potentially soluble. The main worry of many creditors was that shareholders would vote No in the EGM. The primary concern of many shareholders was that they would lose the vast majority of their holdings in the company.

On July 15, those concerns were superseded by the far more pressing and fundamental issue of Afren’s actual oil production. The shortfall was brought to light, according to one source, by Alan Linn and David Thomas, the recently appointed COO.

There followed two weeks of radio silence from Afren, broken only on July 21 when it informed shareholders that the EGM, already delayed from late June to late July, had been adjourned.

There was no further communication with the press, Linn delayed a meeting with Asog, and trading of Afren shares remained dismally silent.

Behind the scenes, much was happening. Afren was writing to its lenders requesting further funding, which, as one creditor said, gave the sense that management was panicking. Newspapers reported that Afren had requested a further $250m. In fact that was just one of the figures put forward: the funding requirements varied based on the different production scenarios considered. There was no clarity as to how much Afren actually needed, and some figures ran into the hundreds of millions of dollars, the creditor said.

Afren seemed to need the money straight away. But it would have taken weeks to assess the request, and even then the answer would likely have been No, he said.

Water in the oil

Two sources close to the matter gave different explanations for the production problems.

The first, close to Afren, blamed the advisers and bondholders. He said that the $200m in interim funding they had agreed to provide at the end of April “weren’t simply deposited into Afren’s bank account” for it to use as it pleased.

Rather, Afren’s advisers and bondholders had oversight of that money and required Afren to be sparing in spending it. That, the source said, had caused delays to works on a new platform at Ebok, one of Afren’s oil fields off the coast of Nigeria and an asset of particular value to the firm.

The original production guidance had depended on that work being completed earlier, including drilling four new wells at the site.

The second source, close to the restructuring, did not contest that account, but said the Ebok problems had only a short term effect on production. Two other issues were of greater concern, he said, because they severely affected the production outlook for the medium and long terms.

One, he said, related to Ebok as well as to Okoro, another field off the Nigerian coast. At both sites, he said, water was infiltrating into the oil extracted.

The Afren source said water was not the firm’s main production problem, the restructuring source said it was.

In offshore oil drilling, water infiltration can result from overworking the field. Asked whether that was the case here, the restructuring source said it might have been.

Another Afren source said water was always present in oil: the problem was that the company’s equipment for mitigating this was running out of capacity.

The second issue cited by the restructuring source related to another asset, also in Nigeria but onshore: OML 26. The output from that field, which should have been 3,000 barrels a day, was severely reduced between January and July this year, he said, because the pipeline leading from the field was sabotaged amid the unrest that preceded Nigeria’s general election at the end of March. The Afren source also said the pipeline had been damaged, affecting output.

Due diligence questioned

The creditor was indignant about the reduced production figures: “Why wasn’t proper due diligence done on production numbers? That was the most basic thing, everything relied on that.”

The restructuring source countered that proper due diligence on the production estimates had been done, by oil and gas consultancy Ryder Scott, and that nobody could have predicted what would happen to production. At bondholders’ request, Afren had engaged Ryder Scott to review its reserve and revenue estimates as they stood at the end of 2013.

Whatever the cause, according to the new estimates, production would be severely down for the next two years, and might be affected for another three years after that, the restructuring source said. For Afren, that meant the company had run its course.

Whatever the strengths and weaknesses of the restructuring agreement, it could no longer go ahead. As one adviser put it: “The problems that emerged were far greater than just about anybody could handle in this deal.”

Morgan Stanley and Blackstone, whose multi-million dollar fees were conditional on the deal being completed, received not a penny. The law firms were paid for the time they had worked for Afren.

Over half of the $48m budgeted as the cost of the restructuring had been spent on a restructuring that didn’t close. The remainder, about $20m, would never be.

[Part 7: Inglorious end] | [Back to main page]

.

Unless otherwise stated in this article, none of the individuals and institutions mentioned agreed to comment on the record.