[Part 6: Torpedo strikes] | [Back to main page]

In the City, some thought Afren’s collapse a scandal, though not a major one. Others had strong words about the outcome.

“It’s the most spectacular collapse on London’s main market since the big bank and retail fails of the financial crisis,” said the head of UK equity capital markets at a major law firm in London, not involved with Afren.

Even Eurasian Natural Resources Corp and Bumi Plc, two other emerging market natural resources companies, are still in business, though in recent years both ran into major difficulties and ENRC eventually delisted from the London Stock Exchange.

In the hours that followed Afren’s announcement, Afren Legal Action led a last minute attempt to organise a takeover of Afren. A member of the group called GlobalCapital that afternoon and said: “We’re trying to move things fast. Obviously after Afren went into administration, times are difficult for us. But we have a company that’s interested, that has been trying to approach Afren for a while.”

Reactions from Afren shareholders, meanwhile, ranged from resignation to outrage. According to a widely circulated claim, several private shareholders had invested all their savings in that one stock and were struggling to cope with their losses.

Little was known of the company, other than that it was incorporated in Nigeria, according to a shareholder who investigated the bid, and the takeover offer never materialised.

The creditor told GlobalCapital that Afren’s demise had been a long time coming, but that it still came as a surprise. Had the creditors known the production figures could not be trusted, no restructuring would have been agreed.

He also said that, with the benefit of hindsight, the takeover options Afren had considered seemed “pretty good”. Asked what would happen now, he said: “No one knows.”

Asset claims look weak

Administration in Nigeria, where many of Afren’s assets are located, is less straightforward than in the UK, he said. The creditor added that the debt was secured on oil field licences or contracts which, for all he knew, could be revoked and prove worthless.

A source close to Afren said it was difficult to know what would happen to the licences, but that they would probably not be revoked for as long as the assets were being worked. With Afren no longer operating, the assets may not be safe from expropriation.

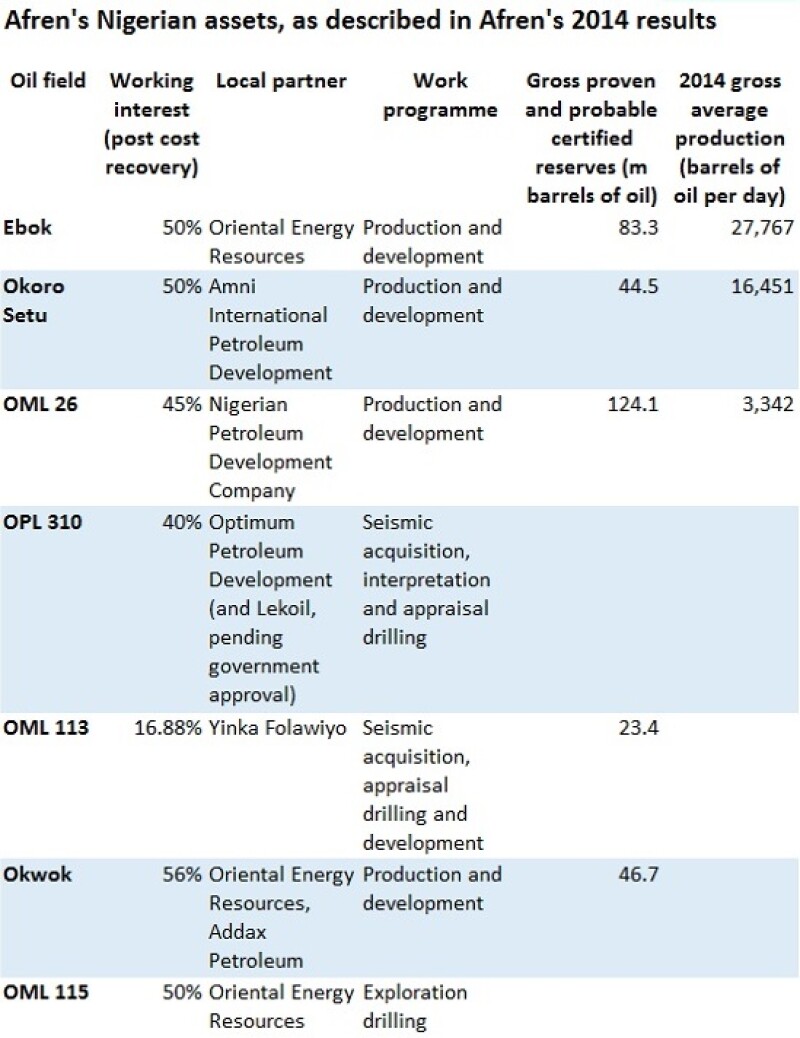

A third source said he expected AlixPartners, the administrator, to focus on protecting the value of OML 26, which is one of the few assets Afren has a strong claim on.

Nigerian laws have required Afren to operate most of its fields as joint ventures with local companies. Two of these, Amni International Petroleum Development and Oriental Energy Resources, involved with Afren in the Ebok, Okoro, Okwok and OML 115 fields, were those alleged by Willkie to have made corrupt payments to Shahenshah and Ullah, the former CEO and COO — allegations denied by both companies.

If Afren loses its interests in any of its oil fields as a result of its insolvency, the JV partners might be among those that benefit.

But in the case of OML 26, Afren’s 45% interest is held through a local subsidiary, First Hydrocarbon Nigeria (FHN), which may give Afren a stronger claim.

Another Nigerian oil field, OML 113, is similar, though Afren and FHN’s interest there is just 16.875%.

Zenith Bank is first in line to claim money from OML 26, as its $100m bilateral loan to Afren is secured on that asset. Access Bank’s $50m loan to Afren is first in line on OML 113.

Because the two banks refused to yield in the battle over the restructuring in March and April, they still have their original security. Other creditors, including Pimco, Ashmore, Halcyon and GLG which put up the new $200m, have junior claims on those fields.

The restructuring source said the $200m had been spent, and could not simply be retrieved from Afren’s accounts.

All Afren’s other Nigerian assets – among them, Ebok, Okoro and Okwok – are likely to return little or nothing, the restructuring source added.

Afren is employed to work on those fields, but does not own even part of them, he said. It will now lack the funds to operate them, and its joint venture partners may well take full control of production.

Afren has a strong claim on fields in other parts of Africa, but those are still exploration fields: they may or may not contain oil and would require substantial investment before reaching production. The Kurdish assets are viewed as worthless.

All three sources said they expected creditors to recover only part of what they had lent Afren, and shareholders to recover nothing.

On Monday, August 10, Afren delisted from the London Stock Exchange.

Lawsuits and investigations

The story will not end there. The UK’s Serious Fraud Office is investigating Afren, according to three sources close to the company. Several district attorneys in the US also are, according to one of the sources. Another source confirmed that the DA of the Southern District of New York was investigating.

One shareholder said SRM and other shareholders were considering suing every party connected with the restructuring, on the basis that either the April production forecasts were wrong, or the July ones were.

Upon considering Afren’s descent into administration, the final scene of Roman Polanski’s film Chinatown — which itself concerns a natural resources fraud in Los Angeles — came to the creditor’s mind.

He said it summarised the mood among those who had worked to save a company that was more deeply troubled than any of them had imagined: the sense of being confounded, and ultimately helpless.

In the film, after two hours of violence and confusion, Jack Nicholson’s character Jake Gittes, still trying to make sense of what had happened, and how it had all gone so wrong, stands before a crime scene, he too confounded and helpless. And is told: “Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.”

Investors in emerging markets, however, cannot forget it. For the parties exposed to Afren —which included many of the leading institutional investors and investment banks — the saga is a painful reminder that, especially when natural resources are involved, the threat of corruption is never far away; that contracts should not be relied on unless they can be enforced; and that oil production is a complex, messy and changeable business.

When management and investors get caught up in the financial architecture, they can lose sight of the ground crumbling under their feet.

.

Unless otherwise stated in this article, none of the individuals and institutions mentioned agreed to comment on the record.