Ever since the global financial crisis of 2008 and 2009, the focus on banks has hardly wavered. Lenders across the world are under unprecedented levels of pressure to improve their balance sheets and raise capital reserves.

India’s banks, in particular, could feel the squeeze.

A period of stubbornly high inflation and persistently strong credit growth is causing rising levels of bad assets for its banks.

True, Indian banks look relatively well capitalised from a global perspective. Yet the country’s state banks in particular need billions of US dollars in extra capital – US$32 billion by 2015, according to ratings agency Fitch – if they are to reliably meet the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) stri ngent capital-adequacy standards.

The trouble is, where to get it? Basel II and particularly Basel III-compliant subordinated bonds are expensive, and there are many questions over how the latter should be structured.

Equity markets look little better. India’s stock valuations have not fully recovered from their tumble last year. The Sensex 30 Index closed out 2011 at 15,455, but after rallying to 18,429 on February 21 it had dropped back to 17,209 as Asiamoney went to press. State bank valuations are riding 28%-38% off of their 12-month historic highs, which occurred in late April 2011.

The state banks appear to believe that New Delhi will bail them out. But public finances are stretched, and the government appears to underestimate just how much money the banks are likely to need.

On March 16, as part of New Delhi’s annual budget, finance minister Pranab Mukherjee announced plans to inject INR159 billion (US$3.13 billion) into the banking sector. Observers say the government may have to reach far deeper into its pockets to capitalise its banks, despite the country’s ballooning public debt.

With Basel III coming into force on January 1, 2013, India’s state lenders have nine months to get their capital in order. Doing so will require navigating choppy capital markets and leaning on the country’s deteriorating public finances.

Current capital realities

When it comes to capital-adequacy strength, the Indian banking system is distinctly two-tiered.

Public-sector banks take around three-quarters of the country’s deposits, yet they have much weaker capital positions than their private-sector counterparts.

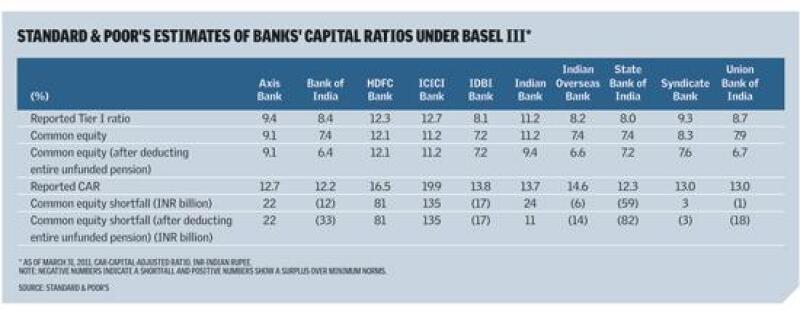

Of the public-sector banks rated by Standard & Poor’s (S&P), the State Bank of India (SBI) – the country’s biggest lender – had a reported Tier I ratio of 8% as of March 31, 2011, Indian Overseas Bank’s (IOB) ratio was at 8.2% and the Bank of India’s (BOI) stood at 8.4%.

Private-sector banks are stronger. ICICI Bank, the country’s largest private bank by assets, has the best Tier I ratio of 12.7%, whereas Axis Bank is the weakest with only 9.4%.

From a top-down perspective, even the weaker state banks look reasonably capitalised. Basel III dictates are likely to place Tier I requirements at 7% of risk-weighted assets.

The problem comes when you look at the banks’ capital on a risk-adjusted basis.

“Indian banks’ risk-based capital is only moderate and that is a weakness for the majority of the Indian banks that we rate,” says Geeta Chugh, an analyst covering Indian banks for S&P. “All the banks meet regulatory requirements but when S&P looks at risk-adjusted capital we feel it’s lower for Indian banks than others in Asia.”

S&P’s risk-adjusted capital measures take into account the differences between banks’ loan books and their exposures to risk, which vary across regions, markets and industries. The system allows the rating agency to better compare banks across geographies than the simpler figures employed by regulators.

The agency estimates the risk-adjusted capital ratio of the Indian banking sector for 2012 will only be 6%. Compared to this, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Singapore boast sector projections of a respective 9.6%, 9.2% and 8.3%.

Even among Asian emerging markets, India underperforms. Indonesia’s risk-based capital ratio is 8%, while Thailand and China are at 6.7% and 6.6%, respectively.

NPLs heading north

Worringly, the country’s ratios may deteriorate this year, courtesy of the fact that the asset quality of its banks is eroding.

SBI offers a good example. The bank’s most recent earnings report in February showed that non-performing loans (NPLs) hit an all-time high of INR400.98 billion (US$8.14 billion) in the fourth quarter of 2011, or around 4.61% of its total asset base.

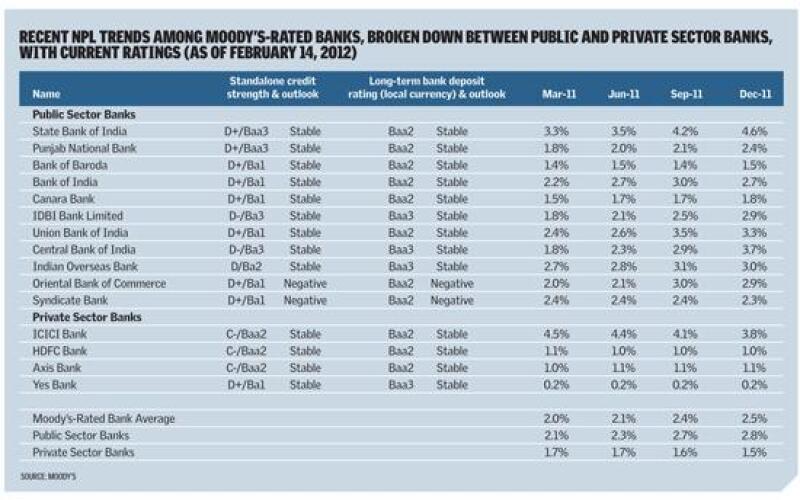

Moody’s estimates that NPLs made up 2.5% of total bank assets and 2.8% of the assets of the public-sector banks it covers at the end of 2011. At the end of March 2011 the figures were a respective 2% and 2.1%, implying a sharp rise in only nine months.

The numbers increase further if restructured loans are included. According to Moody’s, Indian banks prefer to classify weak assets as restructured loans when some form of payment is still being made, despite delays in original payment terms or other covenants being breached.

Add in restructured loans and the estimated total at the end of 2011 was 7.2% of total assets across the banks it rates. That compares to 5.01% at the end of March 2011.

The more NPLs a bank has, the more provisioning it requires as its capital-adequacy ratios – which are measured against risk-weighted assets – deteriorate.

New Delhi pre-empted the negative impact of SBI’s rise in bad debts. On January 30 the bank announced that it would receive a government capital injection of INR79 billion.

Hemant Contractor, managing director and group executive for international banking at SBI, argues that the capital injection has left SBI in good stead.

“With this money coming in and the profit for the current year we would expect that the bank’s capital position will greatly improve,” he tells Asiamoney. “With the government infusion of capital it will take our Tier I capital ratio to 8.2% from 7.7% or so. And with the profits for the current year also coming in I think we’ll be able to take our Tier I capital to 9% on March 31, which is fairly comfortable.”

Contractor, who is the former chief financial officer and now second most senior person at SBI, reasons that the capital was needed less because of asset quality and more because of growth.

“I don’t think the deterioration in asset quality is of such an order that we’ll need additional capital,” he says. “We’re getting things back under control as far as asset quality is concerned and I don’t think there’ll be any requirement of capital for our asset quality issues. Capital required is essentially for our growth plans, we plan to grow [our balance sheet] next year at 17%-18% and with that kind of growth we do need capital.”

Debt deterioration

Unfortunately the rating agencies do not share Contractor’s confidence when it comes to state banks as a whole.

“The asset quality of Indian banks has deteriorated significantly and the expectation is that going forward it could deteriorate further,” Vineet Gupta, Moody’s vice-president and senior analyst, tells Asiamoney.

The banking systems of developing economies with faster rates of growth often experience a strain on asset quality during downturns, as companies that use debt to grow in the good times struggle to repay it when conditions sour.

And India’s economy is slowing. Its gross domestic product (GDP) growth was 6.1% year on year in the last quarter of 2011, versus 6.9% in quarter three. Fitch expects India to see real GDP growth of 7% for the 2012 fiscal year, compared with 8.5% in 2011 and 9.3% in 2008 before the financial crisis.

The asset quality of the banks has not been helped by India’s lack of true bankruptcy proceedings. As Asiamoney reported in our February edition, companies almost never go bankrupt in the country, courtesy of an accommodative legal system. This has led to an irresponsible borrowing culture that is coming home to roost now that economic growth is slowing.

“If the same pace of asset quality deterioration continues over the next 12 months, Indian banks’ total weak assets could exceed 8% on average, and be significantly higher at some individual public banks,” predicts Gupta.

Again, SBI offers a stark example of this. Its NPL ratio of 4.6% at the end of 2011 was the highest in India, while its reported Tier I ratio of 8% was the lowest in the country, according to S&P.

Moody’s typically downgrades banks whose risk-adjusted bad asset ratios hit 9% or higher. Banks nearing this level need to raise new capital to ensure they avoid a downgrade.

Lowering the state bank ratios will require quite a lot of capital.

“We feel new equity required by the system – assuming a minimum core of 9% until fiscal year 2015 – is US$32 billion, of which around 53% has to be the government’s contribution to the public-sector banks,” says Saswata Guha, a director covering banks for Fitch in India.

Fifty-three percent of US$32 billion is US$17 billion, or INR865 billion. Yet in the budget delivered last year the government said it would inject INR60 billion into the banks, while in the most recent budget it promised another INR159 billion in the fiscal year ending March 2013.

Even if you triple the 2013 figure to take into account further capital injections in years 2014 and 2015, the government’s projections look well short of Fitch’s estimates.

“Considering the [government’s] proposed capital injection of INR79 billion into SBI alone for fiscal year 2012, the final numbers [of capital needing to be injected into the state banks] would be considerably higher than the budgeted estimate of INR60 billion,” says Guha.

New Delhi’s projections may be flat-out wrong. Experts believe that the government ended up investing INR200 billion into state banks during the 2012 fiscal year. Plus it injected an extra INR50 billion from Life Insurance Corp. of India, which frequently buys bank equity issues and debt.

It’s entirely possible that India’s state-linked banks require much more money than New Delhi would like to admit.

“INR159 billion budgeted for next year is actually not that high and it will ultimately depend on the fiscal deficit situation in India – which the rating agencies do not see sharply improving any time soon,” says William Mak, a credit analyst at Nomura. “Against the backdrop of weaker asset quality and high loan growth of 18% per annum [Indian banks’] capital positions should be weakening going forward and will require more capital injections.”

Equity options

With the finances of the government increasingly stretched, Indian banks will probably have to turn to the capital markets to raise funding.

But both bond and equity markets present challenges to banks seeking capital.

“The valuation of the equity market is still not conducive enough for [the banks] to come and issue,” says Mak of Nomura.

All of India’s state banks are trading well below the highs they enjoyed back in November 2010. After peaking on November 5, 2010, at INR3,454.79, SBI’s share price plummeted to INR1,571.10 by December 20 last year, losing 55% of its value. India Overseas Bank peaked at INR173.05 on November 4, 2010, but by December 29 last year it was trading at INR73.50, a drop of 57.5%.

Both banks have since recovered – to INR2,062.10 and INR90.60 respectively – but their share prices are well below their former levels.

Some believe the low valuations will make little difference. “They have very little choice given all that’s required, they will have to raise money,” says a senior equity capital markets (ECM) banker covering India. His main concern is timing; he notes that the government takes an inordinate amount of time to decide and approve on its companies issuing equity.

“[The state banks] need the money and they need to be in the market,” he says. “If they have to continue the way they are, then [they should issue] the sooner the better. But how soon the government is going to line up the ducks and do what it takes is a big question.”

Many of the banks, particularly those with lower government ownership, would prefer to conduct rights issues. But that throws up another challenge for New Delhi: should it participate, or allow its stake in these banks to be eroded?

“The big question is if there’s a large government contribution that needs to come in for the rights offer,” says the ECM banker. “It will also depend on how much the government can put [in] and the liquidity of the government in order to do these offerings. That’s something they’d consider before giving approval to some of these banks.”

Investors should be drawn to such rights issues, provided they are priced at a sensible discount to existing shares. Domestic and Asian investors are already showing interest, and demand could come from both long-only funds and hedge funds.

“As long as transactions are sensible and make sense in terms of pricing, you will see deals still getting done irrespective of whether it’s a bank or any other industry,” says the banker. “You will see deals happening in India but once you start to push that [pricing] threshold to unrealistic levels you’ll [start] to have problems.”

But equity is unlikely to prove the only solution for India’s state banks, even assuming they can gain investor interest. Existing investors, including the government, are unlikely to have infinite patience for the banks diluting their shares.

“Equity will continue to be raised but obviously you cannot dilute your equity indefinitely,” sums up a Mumbai-based head of debt capital markets (DCM).

Expensive bonds

The bond markets offer the other obvious funding option. But it also presents some problems.

The global financial crisis of 2008-2009 led to sharp increases in the banks’ capital requirements, most recently with the stringent Basel III rules set to come into effect next year.

Indian banks seeking debt capital via subordinated bonds will need to ensure that they comply with Basel II, and ideally, Basel III.

Both can be expensive. The spreads of Basel II-compliant lower Tier II bonds are approximately 100-150 basis points (bp) wider than senior debt, according to Sean McNelis, regional head of HSBC’s financing solutions group.

Tier I bonds are harder to estimate, given that there hasn’t been one in three years from Asia. But issuers could expect bond yields in the high single digits, roughly 300bp-400bp higher than senior bonds.

In addition, Basel II-compliant subordinated debt will begin to amortise by 10% a year starting from 2013, making it even less attractive.

“I don’t see these banks coming out and raising Tier II capital because these instruments are no longer Basel III capital compliant,” says Moody’s Gupta. “At the same time the cost of conventional Tier II capital instruments is much higher.”

Issuing Basel II is only a temporary solution, given the introduction of Basel III regulations next year. But India’s financial authorities have yet to issue their interpretation of Basel III standards, which makes it hard to do such deals. HSBC’s McNelis thinks the RBI should come to a decision around June, allowing Indian banks to issue in the second half.

Added to that, Basel III subordinated debt costs even more than Basel II bonds because they offer investors less protection (see related story on page 16). The cost and regulatory uncertainty means that Indian banks will be unlikely borrowers.

The caution of the state banks is understandable, but demand for their balance sheets continues to grow. They may have to consider Basel II- or Basel III-compliant debt if they cannot fund themselves through other sources.

“Indian banks are growing quite quickly,” says McNelis. “From a regulatory perspective, issuing hybrid capital helps banks to bolster their capital ratios. We expect to see both Tier II and Tier I capital from Indian banks within the next couple of years.”

Others are less confident. They fear bond issuance will not come quickly, and if it comes at all the costs could be punitive for banks.

“Basel III compliance raises the cost a lot and if you add that to emerging markets spreads it is nonsensical,” says the Mumbai-based head of DCM. “There is a market in India for equity, there are foreign investors comfortable with Indian equity, and if not there’ll be domestic investors [who are] comfortable.”

A web of options

It’s worth emphasising that the situation facing India’s state banks is not dire. These are by no means the worst-capitalised banks in the region.

SBI doesn’t appear overly worried. Contractor says the bank will not offer equity or Basel III-compliant capital yet; instead it intends to issue senior unsecured bonds as part of a medium-term note (MTN) programme, which will do nothing to bolster its capital position.

Tellingly, he believes New Delhi will help out in the event of emergency.

“We may not be tapping the [equity] market right away because we’ve got these funds from the government and next year too we’re likely to get more from the government,” Contractor says. “In the budget, [the government has] made more provisions for capitalising the banks so there may not be an immediate need to tap the equity market.”

The danger of this is that New Delhi’s provisioning proves to be too modest, as Fitch warns. More may be required at a time when the government is facing pressure over its spend-free nature and growing budget hole (it was set to have a fiscal deficit of 5.9% of GDP for the fiscal year that ended on March 31, well above the targeted 4.6%).

Given its deteriorating finances, the state may well be unwilling to indefinitely bolster the balance sheets of SBI and its state-backed cousins.

So New Delhi must make it as easy as possible to let banks raise capital from elsewhere. The central bank could help here by making it clear quickly what it considers to be Basel III-compliant debt structures, to give its local lenders the opportunity to pursue such capital-raising.

The privatisation of further tranches in the state banks, accompanied by the issuance of new shares by the banks themselves, would offer another option. Asset sales could also be considered, although this is less likely given the banks’ rapid growth.

“They’re still growing rapidly so I couldn’t imagine them selling assets,” says Mak of Nomura. “It’s not like European banks which needed to sell assets to boost capital, it’s a different story.”

Curing the cause

It’s likely that India’s banks will be able to find the capital funding they need, even if it proves an expensive process. But doing so will merely relieve a symptom of their problems, not resolve the cause.

Over the longer term the RBI must work with India’s banks to ensure that the quality of their asset books never again becomes so suspect.

For a start, the central bank must force the banks to adopt stricter provisioning for bad debts. It should look at setting caps on debts deemed non-performing or troubled, have the banks curb dividend distribution when asset quality drops and install stricter risk-management processes for credit allocation.

The banks must do a much better job when it comes to lending money. The most important criterion for offering money to a company should be its ability to repay it, not political connections or the profile of the industrialist requesting the money.

Taking on credits such as Vijay Mallya’s Kingfisher Airlines – which has not turned a profit since inception, has deep flaws in its business model, and is now in default to the tune of INR15.8 billion in loans to SBI alone – should not be done so easily.

The government should facilitate this by forcing businesses to enter bankruptcy proceedings if they stop paying their debts. Companies currently suffer no real repercussions from defaulting on their debts, so they have little incentive to pay on time when times get tough. That’s a large part of the reason the quality of state bank loan books is deteriorating.

Until New Delhi tackles these issues, it will need to periodically reach into the public purse to help its banks out, particularly if its economy waxes and wanes.

That is not a long-term solution for a government with a deteriorating fiscal situation.