Just how dire are Japan’s fiscal straits? A standoff in the country’s parliament late last month over passage of a deficit-financing bill left little doubt.

“The government running out of money is not a story made up. It’s a real threat,” finance minister Jun Azumi told reporters on August 31. “Failing to pass the bill will give markets the impression that Japan’s fiscal management rests on shaky ground.”

The stopgap bill is just the latest attempt to plug a widening hole. It follows the stormy passage through parliament the same month of a law to increase Japan’s consumption tax from 5% to 10%, spread over three years. Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda staked his “political life” on the tax hike, intended to slow the steady emptying of public coffers.

Government spending on state pensions, medical and nursing care has ballooned as the population ages, while tax revenues have plummeted due to deflation. Japan’s ratio of gross government debt-to-GDP (gross domestic product), at 220%, is the highest of any developed nation. Only the willingness of the country’s banks and life insurers to keep pouring funds into Japan’s ¥709 trillion (US$9 trillion) government bond market has prevented a liquidity crisis.

“In terms of solvency, there are massive concerns abo ut Japan,” Naohiko Baba, the chief Japan economist for Goldman Sachs, wrote in a gloomy August 14 report. Without making “deep spending cuts in social security” that “will be extremely difficult to achieve politically”, Baba predicts that six years from now Japan will have to turn to foreign investors to help fund the deficit, “as domestic savings dry up”.

There is one obvious alternative to the political poison of massive tax increases or savage spending cuts – privatisation.

“Everyone is jumping up and down about Japanese public debt but is not considering Japanese assets,” notes Stephen Church, a partner at Tokyo-based Ji Asia.

The possibilities of privatisation have been underlined by the coming privatisation of Japan Airlines (JAL), and a plan to sell the government’s half-stake in Japan Tobacco.

Yet remarkably, even the excitement of these two sizeable privatisation issues has not shifted the political debate. Neither major Japanese party is prepared to wholeheartedly embrace the concept of selling assets to raise funds.

It’s a mindset that has to change. Japan’s debts are only going to grow. It needs money and it needs it soon.

Funding constraints

Japan’s fiscal problems are well documented: the result of two decades of minimal GDP growth or outright recession; a declining and increasingly aged population; and lavish government spending on projects to boost jobs, or merely reward, the constituencies of politicians.

These issues have only been exacerbated by the global financial crisis and, latterly, the rule of the DPJ (Democratic Party of Japan).

“The Democratic Party of Japan made unattainable election promises, but the question has remained about how to fund them. The initial plan was to extract waste from the existing system, but that turned up much less than expected,” says Tetsuya Kodama, vice-chairman of Barclays Securities in Japan.

The DPJ has had to jettison most of its early political commitments, such as raising the age limit for child allowances, scrapping highway tolls and cutting vehicles taxes, to avoid bankrupting the country. But it has still worsened the country’s fiscal situation through new farming subsidies and welfare benefits.

“Because economic growth has remained sluggish, and tax revenue hasn’t increased, the cost of servicing the government debt now exceeds tax revenue,” Kodama notes.

“Now the government needs to increase that revenue as much as possible.”

Yet despite the fiscal straitjacket that Tokyo is in, there has been little serious debate about the large-scale disposal of state assets. Indeed, in April this year, the DPJ passed new legislation that abolished a previous requirement to sell shares in Japan Post Bank (JPB) and Japan Post Insurance (JPI) by 2017. The new law also makes it easier for JPB and JPI to enter new lines of business and sell new financial products, making it even harder for private banks to compete.

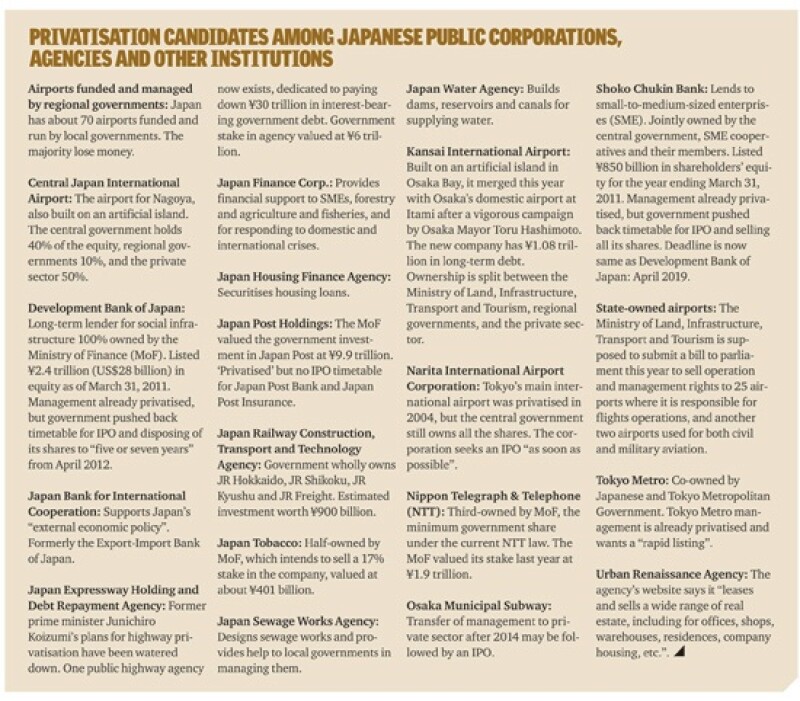

Last year, as the DPJ tried to figure out where an additional ¥13 trillion (US$166 billion) pledged for reconstruction after the March 11 earthquake and tsunami was going to come from, the party circulated a shortlist of possible public asset sales. They included the Ministry of Finance’s remaining one-third stake in Nippon Telegraph & Telephone (NTT), and an initial public offering (IPO) for the Tokyo Metro. In the end, it was agreed only to sell part of the Ministry of Finance’s (MoF) shareholding of Japan Tobacco.

Church thinks naked self-interest lies behind the aversion to privatising state assets.

“[State-run companies are] an enormous amakudari network,” he explains, referring to the notorious practice of Japanese bureaucrats landing cosy sinecures on retirement. (Amakudari literally means ‘descent from heaven’). “Obviously they are opposed to being made redundant.”

Koichi Nakano, a professor of political science at Sophia University in Tokyo, feels that the reluctance to privatise stems more from a need to care for an increasingly elderly population.

“Selling the family silver would bring in money for one fiscal year, maybe two, but it wouldn’t provide the kind of regular revenue that is needed,” he tells Asiamoney. “Another reason for reluctance is the distribution of the ageing population. It is not affecting Japan uniformly, but is more concentrated in remote and rural areas. Unleashing market forces, by privatising utilities and transport and so forth, would do so much political damage to the countryside that no big party would contemplate it seriously.”

Plus there are nationalistic considerations with some state companies. “For national security, when it comes to communications, they need to ensure that a privatised NTT will not fall into the hands of the Chinese, for example,” says Nakano.

Balancing act

This political opposition is why the sale of public assets in Japan has been so limited since the groundbreaking privatisations of Japanese National Railways and NTT in the late 1980s, also the heyday of Thatcherism in the UK.

“When Margaret Thatcher came to power in 1979, the UK balance sheet was nearly, if not quite, as bloated as the current Japanese sector balance sheet,” says Church of Ji Asia.

Church compared the UK and Japanese consolidated balance sheets on a GDP percentage basis for December 2004 and March 2005. He found that the Japanese balance sheet was in excess of the UK balance sheet to the value of ¥372.6 trillion (US$4.7 trillion) in non-financial assets such as land and buildings, vehicles, plant and machinery, along with ¥343.2 trillion in financial assets. The corresponding excess in Japanese over UK liabilities, mainly bonds, was valued at ¥736 trillion, or US$9.4 trillion.

In other words, Japan “could resolve the problem of excessive debt at a disposal stroke”, says Church.

The number of assets the government owns is diverse as well as extensive. The Ministry of Finance helpfully publishes on its website a list, in English, of the largest national properties in its care. As of March 31, 2011, more than 60% of the total value, ¥64.3 trillion (US$820 billion), came from investments. Twenty ‘special corporations’ accounted for ¥21.8 trillion, led by Japan Post Holdings, Japan Finance Corp., the Development Bank of Japan, and NTT.

‘Independent Administrative Institutions’ made up another ¥28.6 trillion, headed by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (¥8.6 trillion) and the Japan Expressway Holding and Debt Repayment Agency (¥6 trillion).

Aiming for IPO

Asset sales may escape their taboo status on the national stage following this month’s IPO of Japan Airlines (JAL).

Restructuring has allowed JAL to emerge from two years of bankruptcy protection as the world’s most profitable airline. The national air carrier axed money-losing routes and one-third of its workforce, while pensions were slashed 30%-50%.

More controversially, the government arranged billions of dollars worth of debt waivers, fresh loans and generous tax waivers for JAL. JAL raised ¥663 billion in the IPO on September 10, all of which will go towards repaying the state’s largesse.

The Ministry of Finance is also selling a 17% stake in Japan Tobacco (JT), valued at about ¥401 billion at market prices.

The DPJ had wanted to sell the government’s entire 50% stake in JT to help fund reconstruction after last year’s devastating earthquake and tsunami. But this plan was thwarted by a dwindling band of 10,800 Japanese tobacco farmers, who are currently allowed to sell all of their tobacco leaf to JT. Fearing loss of this prerogative if JT were fully privatised, the farmers successfully lobbied the opposition Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) to block it by threatening to withdraw its support in parliament for Noda’s spending package.

Looking local

Japan’s politicians will not be able to indefinitely ignore selling stakes in such assets to help service the country’s mounting debt burden. Investment banks are certainly gambling that this will be the case.

Last year, Goldman Sachs set up a new Japanese underwriting group, co-headed by Yasuro (‘Ken’) Koizumi and Makoto Ito, to tap an expected surge in municipal demand for financing. Mitsunari Okamoto was put in charge of another new group focusing on the public sector, infrastructure and utilities.

In July, Barclays Securities Japan appointed Kodama as a new vice-chairman, with a brief to develop a new public-sector advisory and underwriting business for the bank.

The intransigence of politicians about asset sales and their willingness to bow to lobby groups has led investment bankers to believe that assets owned, in part or entirety, by local governments are the most likely to be privatised – at least initially.

“The Ministry of Finance wants local authorities to sell off assets and pay down public debt, and has been putting sustained fiscal pressure on them,” says Church. “The Ministry is against privatisation of its own assets, but is in favour of other people’s assets being privatised.”

Toru Hashimoto, the brash and forceful mayor of Osaka who is launching a new national party to challenge the DJP and LDP, wants to transfer management of the city’s subway system to the private sector after 2014. The Osaka Municipal Subway made a ¥167.7 billion profit in the 12 months to March 31, and carries debt of ¥597.6 billion.

Another contender for privatisation would be the Tokyo Metro, the busiest subway system in the world. It has been privately managed since 2004 but remains under public ownership, with the national government holding 53.4% of shares and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government the remainder.

The company’s website says the goal of management is “to strengthen our profit structure to allow the rapid listing of the company”. However, an IPO keeps being derailed by entanglement with debt-ridden Toei Subway, a separate network built and still operated by the Tokyo government that uses a different track gauge to Tokyo Metro.

Then there are Japan’s 98 civil airports, most of which were built to please local voters. Nearly all lose money; no surprise given that they often compete against the shinkansen, or bullet trains that operate on the world’s most extensive high-speed rail network.

Local governments operate more than two-thirds of the total airports available and the state runs flight operations for most of the rest. They should be prime targets for privatisation or closure. The Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism has been tasked with drawing up a plan to sell management and operation rights to 27 state-owned airports for periods of between 30 and 50 years.

Asiamoney sent the Ministry a list of 21 questions about privatisation of assets but received incomplete answers. A table for only 25 out of the 27 airports showed that half lost money from flight operations in the fiscal year ending March 2010.

The value of liquidity

In theory, Japan’s water industry could also provide rich pickings for infrastructure consortia, including foreign banks.

At present, the Japanese water industry is highly fragmented, like that of the UK before it was restructured under public ownership in the 1960s and 1970s. For example, there are more than 1,600 Japanese water companies managed by municipalities and prefectures.

Osaka is leading the way in consolidation. Hashimoto, the mayor of Osaka city, is pushing to integrate the city’s water supply with the 42 waterworks run by municipalities in neighbouring Osaka Prefecture, of which he used to be governor.

Even Osaka City Hall concedes that it faces an uphill battle in winning the understanding of citizens to transfer ownership of the water system to the private sector. So far, the only foreign water company to have won any Japanese concessions is Veolia, which operates two sewerage plants in Hiroshima and Kyoto and the treatment of drinking water for the small tourist city of Matsuyama on Shikoku Island. The three contracts bring in only €49 million (US$61.6 million) in revenue.

Observers note that privatising water companies would be far more sensitive with the populace at large than selling off rights to airports.

“With water companies there are politically and socially sensitive issues, such as water purity. Such issues make the IPO of a water company highly unlikely,” is Kodama’s view. “With airports, those being considered are not financially viable, and so a political decision on taking over the existing debt needs to be addressed. This is again not easy, but with airports there are fewer sensitivities than for water.”

The companies themselves don’t appear keen. Asked whether privatisation has been discussed, a testy Chie Kasugai of the Tokyo Waterworks Bureau emailed Asiamoney an emphatic “No”.

Urgent renewal

Barriers to privatisation could yet be overcome by another little-discussed factor. The country’s infrastructure needs renewal, and it won’t be cheap.

Barclays’ Kodama notes that the depreciation of public infrastructure assets typically lasts over 60 years, after which they are deemed to be in need of an overhaul. But the last time the nation really embarked on massive infrastructure building was in the five years after World War II, now just over 60 years ago.

“Most of the roads, bridges, tunnels, etc., are reaching the end of their safety period. This is still not something that is being widely debated yet. The conversation is still about the cost of the new bridges and shinkansens and highways, even years after the end of the bubble,” says Kodama.

The bill for rebuilding on this scale would be hundreds of billions of US dollars, and neither the local nor central governments are in any position to foot it. That means private financing will be essential.

“We will certainly need to discuss the use of PPP [public-private partnerships], revenue bonds etcetera to fund infrastructure investments going forward, but the real need will come from updating the essential infrastructure, not the new roads and bridges,” according to Kodama.

“It will be extremely difficult to pay for all this reconstruction of existing infrastructure by just dumping it on the public finances. The crucial question remains, how will it all be paid for?”

Are the Japanese really against privatisation?

The future of privatisation in Japan is hard to assess. While politicians seem dead against it on a national level, the nearest the country had to a popular plebiscite on selling state assets was the lower house election of 2005, called by then-prime minister Junichiro Koizumi after the upper house rejected his bills to privatise Japan Post. Koizumi won the election by a landslide.

These days, it is rare to hear any Japanese criticise the break up of the old Japanese National Railways, which has become a model for railway privatisation the world over. Japanese anxieties about water ownership also echo those expressed by the British before the UK water industry was privatised in 1989 and its assets later sold off.

Safety issues are genuine nonetheless. Nakano of Sophia University believes the underlying reason is primitive Japanese regulation of utilities compared to that of the UK.

“In Japan, what often happens is that the bureaucrats, who are much more dominating, political and meddlesome than British civil servants, still get amakudari positions” overseeing the private sector, Nakano points out. “So taking corporations out of the public sector is not necessarily going to make them more accountable.”

The most notorious recent example is that of regulators responsible for nuclear safety at Tokyo Electric Power (see box on page 32).

Even so, the most compelling rationale for more privatisation in Japan is economic and financial. Freeing companies and whole industries to compete can only stimulate growth.

Privatisation may ultimately prove a more palatable medicine than raising taxes or slashing public spending, and be better for the economy too.