Modern commentators often point to “elite overproduction” as a driver of today’s political tensions. The theory goes that an excess of highly educated, ambitious individuals are competing for a limited number of top positions in government, industry, media, and academia.

This dynamic fuels resentment among the top 5% toward the top 1%, breeding conflict. This explains, for example, why higher-income Democrat voters supported Zohran Mamdani in the New York City mayoral race, while lower-income go more for Andrew Cuomo.

I am no political scientist and can’t say whether this accurately diagnoses our political ills, but elite overproduction is a fitting lens for investment banking. There are only so many corner offices to claim, and ambition far outstrips supply. Yet whereas only one candidate can be mayor of the Big Apple, the investment banking industry, with its knack for adaptation has a creative solution: co-leadership.

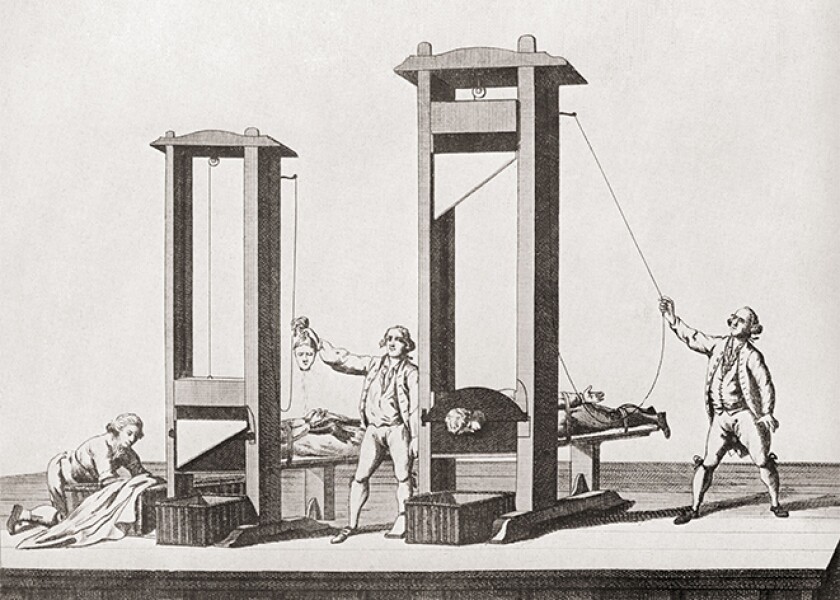

It’s genius when you think about it. Two people, one title, and the delicate pretense of seamless collaboration. On paper, it’s elegant. In practice, it’s a fragile truce of clashing egos and thwarted ambition, often devolving into low-grade guerrilla warfare.

Bankers know the drill by now: two senior executives sharing one role, speaking in unison, moving in perfect sync. They stand side by side at town halls, copy each other into emails religiously, and maintain a flawless façade of unity — at least in public.

Beneath the surface, the reality is often different. One may command a bigger pay cheque, enjoy closer ties to leadership, or simply wield sharper political instincts.

On paper, they’re equals. In practice, there’s almost always a hierarchy, no matter how faint. The arrangement hums along until it doesn’t. And when it fails, the fallout is anything but tidy.

What makes the co-head model so absorbing isn’t just that it exists — plenty of industries have their own versions — but how investment banking has elevated it to an art form.

Perhaps it’s because talent in this business is notoriously footloose; a senior banker with a bulging Rolodex can be here today, poached tomorrow. Or maybe it’s the sheer sprawl and complexity of modern banking operations, where the job really is too big for one person.

Then again, it might just be the industry’s obsession with succession planning: rather than picking a winner outright, banks often prefer to pit contenders against one another and see who emerges with fewer knife wounds.

The trouble is that the co-head arrangement survives on the illusion of perfect equilibrium. But that is sometimes difficult to sustain over a long period of time, especially at a time of market stress.

Let one slip show — a conspicuously missed meeting invitation, a bonus round that exposes a pay gap — and the whole delicate performance unravels.

What began as a civilised power sharing pact devolves into a backroom brawl full of whispered betrayals, thinly veiled jabs in all-hands memos, and the inevitable “mutual decision” for one to “explore new ventures” just as soon as their severance package is ironed out.

In better times — certainly in M&A and equities — when fees were fat and revenues rising, these internal dramas could be safely contained. But the past couple of years have been anything but buoyant.

With deal volumes anaemic and equity capital markets sluggish, banks have turned inward. Layers of management are being peeled away, and senior bankers — especially those in flagging regions or faltering divisions — are feeling the heat. Against this backdrop, co-head arrangements, always a bit of a gamble, become brittle.

And yet, for all the internal upheaval, the broader market barely shrugs. Shareholders, by and large, are indifferent to palace intrigue. If the numbers hold up, the occasional headline grabbing departure is just noise.

The real concern is margin, not melodrama, and if one co-head meets his or her maker — professionally speaking — then so be it. Bankers may stew over slights and status, but investors are focused on the bottom line.

And yet, for all the internal upheaval, the broader market barely shrugs. Shareholders, by and large, are indifferent to palace intrigue. If the numbers hold up, the occasional headline grabbing departure is just noise

And let’s be honest: conflict, however unseemly, is baked into the DNA of this business and is often seen as an operational positive, keeping bankers on their toes and preventing complacency from creeping in.

Competition doesn’t stop at the firm’s edge; it thrives within its walls.

What has changed is the discretion. Once, these struggles were cloaked in corporate euphemism. Departures were choreographed, rivalries smoothed over, and no one admitted — publicly, at least — that the emperor’s lieutenants weren’t getting along.

But in the last few years, the gloves have come off in spectacular fashion. Whether it’s a shift towards transparency, a decline in institutional patience, or just the reality of a more punishing market, the veil has lifted to some degree.

The same hunger that drives people to the top makes them, more often than not, spectacularly bad at sharing the summit.

For all the industry’s sophistication in structuring deals and managing risk, it still hasn’t cracked the most delicate challenge of all — getting two alphas to play nicely in the same sandbox.