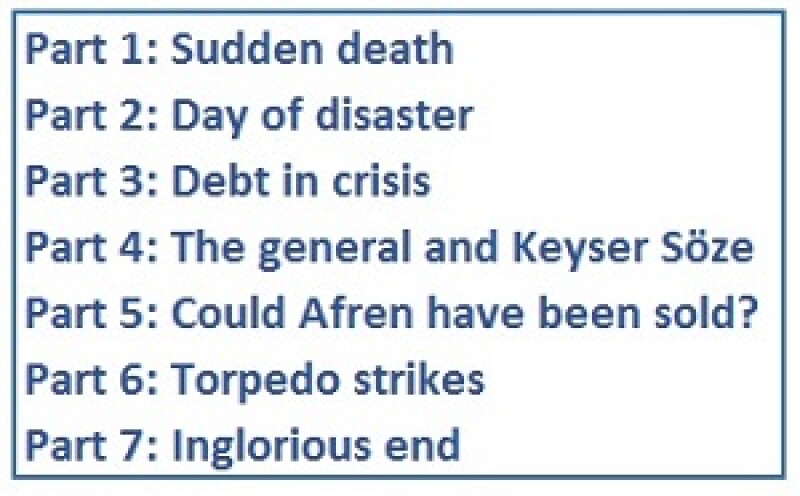

[Part 4: The general and Keyser Söze] | [Back to main page]

There was some interest from buyers. In April, when Alan Linn knew he would be made CEO of Afren but the news was still not public, Fosun, the Chinese conglomerate, contacted him, to ask if he would lead its effort to buy Afren. Fosun did not realise it was addressing the group’s future head, according to a source close to Linn.

An Afren source said Fosun’s approach had been earlier, in December-January.

Seplat, a Nigerian oil company, was also interested. Afren first announced it had received a “highly preliminary approach” from Seplat on December 22, 2014, and eventually discarded the approach in mid-February.

People involved with Afren disagree widely about whether a deal with Seplat was ever a real possibility, and which side was more to blame for it not happening.

The head of energy research at an African bank said he had worked on one serious offer besides Seplat’s and Fosun’s. He said he thought Seplat’s offer had been the best.

He told GlobalCapital : “It [the Seplat bid] clearly had the most impact and could have corrected the perception of Afren — Seplat had a strong corporate governance culture and operational excellence story, which would tie in quite well for Afren, which was the exact opposite.”

According to a source with close contacts at Afren, Seplat offered “90p a share, to buy 100% — debt, Kurdistan and all”, meaning it would honour Afren’s debt and knew about the Kurdish asset writedown.

The source said: “Seplat’s offer was very good. Afren didn’t consider it properly.”

On March 26, over a month after Afren had said Seplat’s bid was void, Seplat’s CFO Roger Brown said in a presentation about the firm’s 2014 results: “We had put together a structure which we believed was good for all capital providers, particularly aimed at stabilising the business and insuring continued oil into the future. The Afren board decided not to proceed with that and then locked us out of that [sales] process.”

He added: “We’ve done an awful lot of work on the assets, in detail, and some assets are more structural and better for us than others. Some actually would work quite well within our portfolio. We remain interested, we wait to see what the bond process does and I think the company will need quite a lot of investment to stabilise it, and then we’ll see what the management of the company decide to do. To the extent that they do decide to sell off, or sell off in piece, then we would certainly remain interested to talk to them about it.”

Afren disagreed about the quality of Seplat’s offer. It said on February 13: “The Board has not received any proposal from Seplat that it believes is capable of being implemented on terms satisfactory to all relevant stakeholders in the Company, including the indicated value being significantly below the aggregate value of the debt of the Company.”

Two other people close to Afren described the claim that Seplat had offered to buy the whole of Afren at 90p a share as “nonsense”.

There was disagreement over the takeover discussions. The head of energy research said: “I think they [Afren] took the brinkmanship play too far”. He pointed in particular to two of Afren’s Nigerian assets, Okwok and OPL 310, for which Afren had a “clearly higher valuation” than prospective buyers had.

A further stumbling block was the revision of Barda Rash estimates, which pointed to “major issues” around “the true picture of their reserves”, he said.

A manager at a multinational oil and gas firm that did not bid for Afren echoed that point: Afren’s reserve estimates had become questionable after the revelation about Barda Rash.

A person who worked on the restructuring said some of the bids had come from serious parties, but that the bids themselves were never serious. When told that some viewed Seplat’s approach as the most convincing, he said: “That’s frightening if Seplat’s was the best.” He added that Seplat’s offer had never exceeded two pages, and contained no numbers.

He said that even Rothschild, which gave M&A advice to Afren on the Seplat bid and was only to get a fee for its work if the takeover actually took place, eventually realised Seplat was not serious in its approach.

He added: “The only way for the Seplat offer to move forward is if the bondholders were willing to engage with them around a restructuring of the debt at a price significantly below par. The bondholders and the ad hoc committee and their advisers expressly rejected any willingness to engage with Seplat around that. Without them being willing to engage, the company couldn’t pursue the transaction, because Seplat was not willing to make an offer that took care of the bonds.”

In other words, Seplat never agreed to honour Afren’s entire debt, he said, adding that this was true also of all other potential buyers.

Had Afren received a serious bid for any or all of its assets, the firm and its bondholders would have accepted it, potentially instead of the restructuring, he said. “Afren was wide open to potential alternatives,” he added.

Another general?

Even after these fruitless takeover talks between Afren and several firms, Afren Legal Action solicited other potential offers on its own.

However tenuous some of these were, Afren Legal Action felt they were at least worth exploring.

One such was received on June 27, when a man claiming to write “on behalf of one of the largest Capital Investment Groups in the US” forwarded to Afren Legal Action an email he had sent to Afren, in view of starting takeover talks. The email read: “The Group involved is Kholberg, Kravets and Roberts (KKR) Global Institute headed by General David Petreaus. I believe he would be particularly interested in the Kurdish properties because of his background, experience and knowledge of the area and its key players.”

Retired US general David Petraeus is indeed chairman of the KKR Global Institute, but a spokesperson for KKR told GlobalCapital : “The emails you received were not sent on behalf of or at the request of KKR.”

[Part 6: Torpedo strikes] | [Back to main page]

.

Unless otherwise stated in this article, none of the individuals and institutions mentioned agreed to comment on the record.