The Indonesian blogosphere is indignant. Corruption scandals plague president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s Democratic Party. Labour discontent is rising, industry is frustrated by poor infrastructure, and traffic gridlock is unpleasant. Plus the rupiah is depreciating.

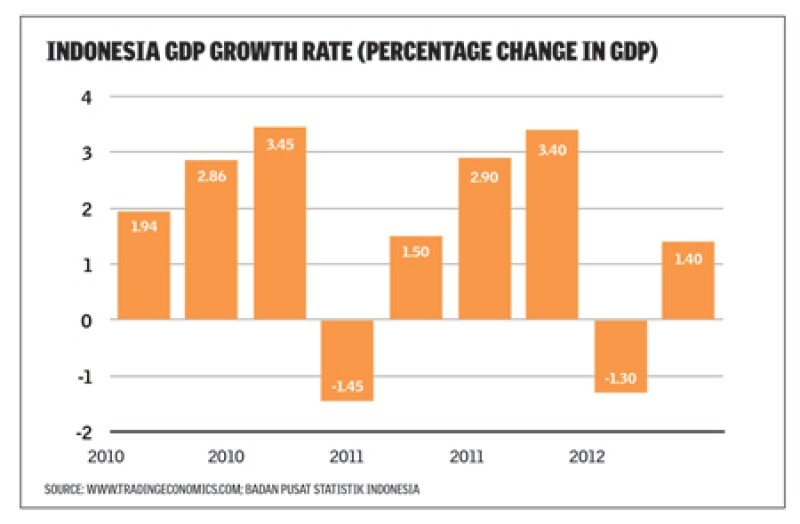

On the surface, such stirrings look like run-of-the-mill griping in a nation doing rather well. Indonesia’s gross dometic product (GDP) rose 6.3% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2012, capping nearly six years of more than 6% annual growth. By 2015 the number of millionaires is expected to triple to 99,000, according to wealth management firm Julius Baer, the fastest growth in Asia.

Even the poor are faring better. Unemployment is at a record low of 6.3%, while only 30 million people, or 12.5% of the population, live below the national poverty line. There is nearly universal primary education, with participation rates at 95.3%.

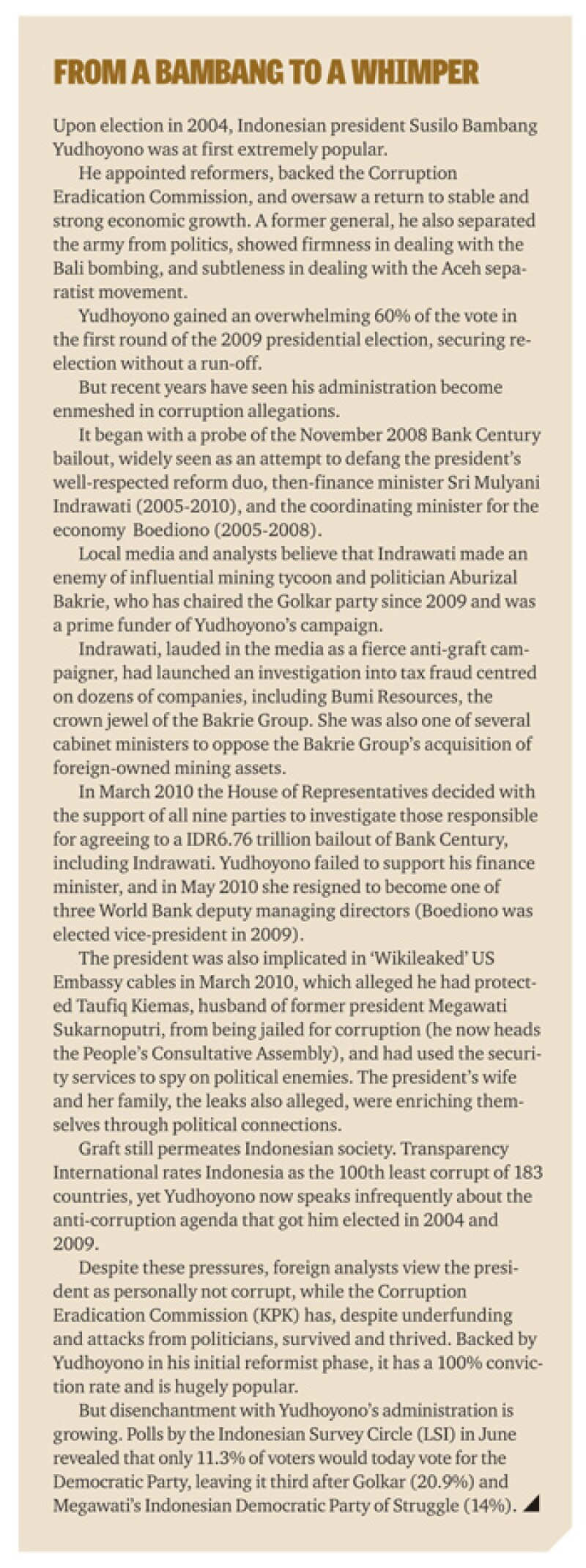

But all is not well. There is deep disillusionment with the political elite. In April, the Democratic Party’s former treasurer Muhammad Nazaruddin was sentenced to five years in prison for accepting bribes in connection with dormitory contracts for the Southeast Asian Games. He in turn accused Democratic Party chairman Anas Urbaningrum and youth and sports minister Andi Mallarangeng of taking kickbacks to rig a IDR1.2 trillion (US$128 million) sports project bid.

Meanwhile Wafid Muharam, the youth and sports ministry secretary-general, and Democratic Party lawmaker Angelina Sondakh, the former Miss Indonesia, have both been detained for corruption.

“Indonesians understand that corruption occurs in politics,” says Shaun Levine, Indonesia analyst with Eurasiagroup. “But the fact that corruption is occurring at such a high level, when the Democratic Party was built on anti-corruption and the people who are being charged with corruption are the ones who were seen as the reformers, that is disillusioning.”

These corruption concerns have bogged down the once-reformist agenda of increasingly lame-duck president Yudhoyono. And that appears to have prompted him to give the green light to Hatta Rajasa, his coordinating minister for the economy, to veer in a bizarre protectionist direction. Observers suggest that the central thread of Hatta’s policies is to serve politically connected special interests, but they risk damaging the goodwill the nation has earned with international investors.

Now would be a particularly poor time to squander Indonesia’s momentum on intra-factional power struggles.

Pushing protectionism

Yudhoyono was twice voted in as Indonesian president largely on the prospect of fighting corruption. But recent events have eroded his administration’s ability to campaign under such a mandate (see box on next page), and it wants to shore up slipping public support ahead of the 2014 presidential elections.

To do this the government is pushing a ‘Master Plan’ written by the National Economic Committee two years ago, primarily to develop infrastructure. Additionally all parties are becoming increasingly nationalistic.

Hatta has emerged as a key figure and over the past two months he has introduced a deluge of protectionist policies dubbed “Hattanomics”.

Firstly, foreign investors in mining must begin divesting to Indonesian entities within five years. By the sixth year Indonesians must own at least 20%, by the seventh 30%, 37% in the eighth, 44% in the ninth and 51% by year 10.

Secondly, from May 6 trading curbs were applied to exports of 14 metals including iron ore, manganese, gold, silver and copper to encourage the building of domestic smelters. Exports will be limited to refined exports only.

A government-linked company, the Indonesian Ports Corp., is to build a US$1.9 billion new port at Tanjong Priok in North Jakarta – the biggest infrastructure project in Indonesia’s history. The government cancelled international tenders for the project, outraging private-public consortia that had devoted considerable funds to preparing bids.

Additionally, on May 31 Bank Indonesia announced it would issue new rules limiting international ownership in local banks, three weeks after Singapore-based DBS Holdings Group announced a US$7.2 billion deal to take over Bank Danamon, Indonesia’s sixth-biggest bank. The Bank Danamon takeover is now on hold, disappointing at least three other foreign banks with Indonesian acquisition plans.

Finally, parliament is pushing for a draft law on trade that could authorise the Ministry of Trade to stop imports or exports on several broadly defined criteria. These include guaranteeing the availability of goods on the domestic market; or minimising price fluctuations; or to protect the health, security and values of society. In other words they can be implemented at almost any time.

Vested interests

From one perspective, these protectionist rules merely bring Indonesia in line with other Southeast Asian countries.

In Singapore, the prime minister’s permission is required for foreign companies to take stakes of more than 5% in local banks. In Malaysia foreigners cannot own more than 30% of banks. Many feel that since the 1997-1998 Asian financial crisis foreign banks have enjoyed too free a rein when buying into Indonesia banks.

Encouraging upstream resource production also makes sense.

“The creation of added value has nothing to do with nationalism or protectionism. It’s a necessity,” said former president Bacharuddin Jusuf Habibie at a recent gathering of researchers and innovators in Jakarta.

But observers believe powerful companies are lobbying lawmakers to protect themselves.

“Protectionist policies are being put in place in sectors dominated by domestic interests,” says Levine. “Mining for example is dominated by domestic mining companies – Bumi Resources [controlled by resources tycoon and Golkar Party chairman Aburizal Bakrie], Adaro [controlled by local entrepreneurs including Edwin Soeryadjaya, Theodore Permadi Rachmat, Garibaldi Thohir, and Sandiaga Salahuddin Uno], Beral Coal [controlled by Rosan Roeslani via Bumi PLC]. All these are very much embedded into politics.”

As yet there are few signs of foreign direct investment (FDI) flagging due to these measures. But concerns are growing. On July 12 Myron Brilliant, senior vice-president of the US Chamber of Commerce, told The Wall Street Journal that “we’ve seen an increase of what could be described as forced localisation” in Indonesia, in which officials push policies that promote local products over international ones.

“These regulations are being drafted in the dark,” with no consultation of companies affected by them, he added.

The president’s problem

The influence of business on Indonesian politics is largely due to the country’s political setup. Many political parties count wealthy businessmen as key supporters or even leaders, as in the case of Bakrie. Added to this, governments are invariably formed from coalitions.

Yudhoyono’s Democratic Party holds only 150 of the People’s Consultative Assembly’s 560 seats, and rules with support from other parties, principally Golkar and the moderate Islamic National Mandate (PAN) Party, chaired by Hatta.

Yudhoyono’s support for the policies offered up by Hatta – whose daughter is married to the president’s younger son – appears a tactical move ahead of the 2014 elections.

Yudhoyono cannot stand for re-election. Three possible presidential candidates have emerged: Bakrie, Megawati and Prabowo Subianto, former commanding general of the Indonesian Armed Forces special operations group Kopassus and son-in-law of Suharto.

All three candidates represent entrenched political and business interests. Two have frosty relations with Yudhoyono.

“There is a lot of ill-will between Yudhoyono and Megawati, and between Yudhoyono and Prabowo,” says Kevin O’Rourke, the head of Reformasi Information Services. “The Yudhoyono administration allowed the Corruption Eradication Commission to jail quite a few Megawati cabinet members, the latest being former four-star General Hari Sabarno [jailed in January]. And Yudhoyono cashiered Prabowo from the army in 1998 [for involvement in the anti-Chinese riots and kidnapping pro-democracy activists]. So either of them could be vindictive.

“Bakrie would be relatively safer [for Yudhoyono]. He is therefore testing the waters for a Golkar-Democratic alliance before the election.”

Hatta is another possible presidential candidate, but he suffers from not being Javanese, the dominant national group. Yet he is ambitious, quite popular and is taking personal credit for the Master Plan.

Frustrations and delays

While political pressures distract Yudhoyono from his original reform path, Indonesia is bursting at the seams.

With only 6.3% unemployment, labour militancy is on the rise – and so are wages. Over the past eight months there have been six major strikes or labour demonstrations – at Freeport in 2011 (settled by a 40% increase over two years); in Batam (19% minimum wage rise); in Bekasi (16%-30% increase agreed); in Medan (7%-12% increase of wages across North Sumatra); again in Bekasi at the PT Suzuki Indomobil plant.

And on May Day there was an unusually tumultuous gathering of more than 161,000 workers across Indonesia.

Another major problem is infrastructure. Since democratisation in 1998, infrastructure spending has fallen from 8% of GDP a year to roughly 3% in 2011.

The number of vehicles per public-road kilometre almost tripled between 2000 and 2009. Four out of the top five international airports, including Jakarta’s Soekarno-Hatta, are operating at above 100% capacity.

Inadequate infrastructure and inefficiencies are slowing trade. Shipping a container from Jakarta to Padang, West Sumatra, is four to five times more expensive than shipping it from Jakarta to Singapore. A sack of cement is 10 times more expensive in Papua than in Jakarta.

Energy accounts for up to 30% of production costs in the ceramics industry, and 40% in the metal industry.

To keep up with its expanding economy, Indonesia needs to invest at least US$30 billion into infrastructure every year, with US$18 billion-US$20 billion from the private sector, say practitioners. Yet out of some 79 public-private partnership (PPP) projects offered since 2006, valued at US$53 billion, only one has been put in place, according to national planning agency Bappenas – a power project in Central Java currently in its early stages.

The government has not even been able to persuade parliament to reduce fuel subsidies. Parliament rejected the government’s proposal to raise subsidised fuel prices by 33% on March 31. Instead lawmakers approved a system in which price increases are allowed only after the average cost of fuel has exceeded US$120 per barrel for six months.

As a result the government expects to overshoot its fuel subsidy spending forecasts by IDR100 trillion, adding to a projected budget deficit for the year.

Poor policy implementation

In fairness, the much-needed Law No 2/2012 on Land Procurement was passed without pressure from the president. The new ruling is designed to force landholders to sell real estate to the government, a pre-requisite for many infrastructure projects.

But it still awaits implementation regulations. Property holders will want attractive compensation or they could resist, clogging an overburdened court system and further delaying needed roads, railways and power plants.

Such decision-making has been complicated by decentralisation from Jakarta to the provinces. “Over the past few years there has been a diffusion of power throughout the country,” says Levine. “For Yudhoyono, this has made governance extremely difficult.”

A paper published by Lena Herliana of the Indonesian Chamber of Commerce and Industry makes depressing reading. Little hope is seen of a pickup in infrastructure spending, given weak political commitment, a lack of target spend levels, overlapping regulations (there are four different and contradictory sets of regulations for logistics), a lack of cost-benefit analysis, frequent judicial review, and the dominance of petty political interests.

“There is no shortage of projects in the pipeline, but there is poor implementation,” says Tony Nafte, senior economist at CLSA. “Poor policy implementation means that you are not going to get 7% [annual GDP] growth.”

In a May report, titled Indonesia: does bad policy matter?, Nafte wrote: “Previously – no, it didn’t matter,” he says. “But now, we think it does.”

“Hatta-economics and corruption are basically blocking reform,” he adds.

One example was the plan by state-owned enterprises minister Dahlan Iskan to appoint new management into the 141 state-owned enterprises and give them the right to hire at their discretion. Parliament revoked his reforming ministerial decree.

Maintaining momentum

Indonesia still has leeway before such frustrations truly hurt its progress.

FDI rose 60% to US$17 billion in 2010, and then to US$19 billion in 2011. Total first-quarter investment amounted to IDR71.2 trillion, 32% up from the same period of 2011. The country’s external debt ratio was 25% of GDP in 2011, versus 156% in 1998. Foreign exchange reserves were US$116 billion in April.

Plus the government recently gained ratings upgrades from Fitch and Moody’s to investment grade – although tellingly Standard & Poor’s has held back from raising its ‘BBB+’ rating, having grumbled about policy developments inhibiting growth.

But the country needs further reform to achieve its growth potential. In a telephone poll conducted this May by the Kompas newspaper, 70% of respondents agreed that there is a need for a reform movement – a new reformasi.

Yudhoyono looks unlikely to supply it, preoccupied as he appears to be with a desire to safeguard himself as a retired president. Parliament appears unwilling to countenance such bold actions, riddled as it is by factionalism and competing business interests.

And the most likely presidential successors appear to represent some of Indonesia’s most vested interests; it seems unlikely that any would wholeheartedly embrace the costly reforms of an economy that benefits them just as it stands.

Indonesia’s 2014 presidential election could define whether the largest country in South-east Asia builds on the momentum developed during much of Yudhoyono’s presidency, or falls back into old habits.

The country needs a presidential candidate committed to transparency, fighting corruption and delivering reform. Indonesia needs someone much like Yudhoyono himself, eight years ago.