Without proof, it’s hard to see what makes a green bond green. Issuers can say that a bond will be used for environmentally friendly purposes, but establishing the truth and the credibility of that claim is crucial. The green bond market has always known this is essential to the product, and the issuers that pioneered the industry strove to reassure investors that green bonds were more than just branding.

But the rapid development and expansion of the market has created a tension. If establishing green credentials is too onerous, this will discourage new issuers from setting up programmes and ossify market structures. But if the bar is set too low, it will devalue the whole idea of a green bond.

“One school of thought says ‘don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good’,” says Stephanie Sfakianos, head of sustainable capital markets at BNP Paribas in London. “It broadly improves the environment to have more issuers involved, so we shouldn’t do anything to discourage them.”

She continues: “The other [school of thought] says that if green bonds are not robust and rigorous, then it’s just well-meaning people with generic socially responsible approaches. But in the end, asset owners fall into both camps.”

But for all that, second opinions, third party verification, certification, impact assessment and so on are strictly optional. The only absolute requirement for a bond to be a green bond is that an issuer says it is.

“Compliance is completely down to issuers,” said Doug Farquhar, principal consultant, sustainability and innovation at DNV GL, a sustainability consultancy that provides second opinions of green credentials based in Oslo. “At the moment, there are no explicit penalties for breaching commitments. The only recourse investors have is pursuing issuers in the courts to achieve a technical default.”

But at the same time, the more credibility an issuer can bring in from external parties, the greater the reputational impact of setting up a green programme in the first place will be.

Having some form of external verification also comes with a host of advantages, such as eligibility for certain bond indices and for a green bond listing on the Oslo or London Stock Exchanges, and extra attraction for some investors. But it does not mean tighter spreads.

“Green bonds have no subsidy, and don’t trade tighter than ordinary bonds, so no mechanism exists to pass on the cost of an in-depth review to investors,” says Christopher Flensborg, head of sustainable products and product development at SEB in Stockholm.

But if the purpose of the market is mainly to signal environmental virtue, to drive internal change and to foster the culture and apparatus for environmental monitoring in financial markets, then the stronger the external endorsement, the better.

Proof givers

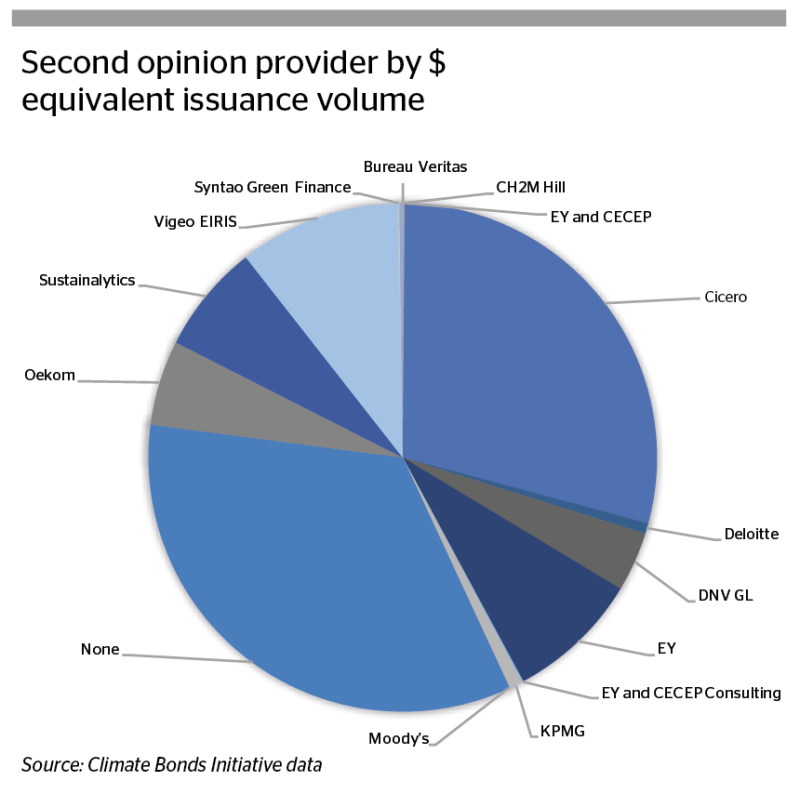

The industry of providing credibility to potential green bond issuers has been with the market since its early days, with Norwegian NGO Cicero pioneering the market, through mandates on many early supranational, sovereign and agency (SSA) issues.

Since then, the market has proliferated. Consultancies such as DNV GL, alongside specialist firms such as Oekom and Vigeo, are the mainstay of the verification industry. This year, however, Moody’s launched its ‘green bond assessment’ approach, bringing a rating agency approach into the industry.

“The presence of Moody’s is definitely positive for the market,” said Cefas van den Tol, head of corporate origination at ING in Amsterdam. “Hopefully it will allow investors with different levels of green commitment to categorise their bonds differently, and perhaps look at relative value for a given level of green.”

Credit ratings are, indeed, the obvious analogy to the various forms of external validation that exist. Both business models involve the issuer paying for an evaluation, which is then published to give investors more information — and encourage them to purchase bonds. But that creates an inherent conflict of interest.

Farquhar says: “We’re very aware of the issues that impacted the [credit rating agencies]. We have a robust conflict of interest process, and how we are paid for the work is a big part of that. For example, we require that the issuer pays us, not the bond arranging bank, or any third party.”

Sustainalytics, the dominant provider in North America, sees its opinions as a strengthened form of issuer communication to investors — an opportunity to lay out what is behind the green bond in a rigorous format, with commentary.

While there’s no official market standard for the international green bond markets (local regulations are under discussion in China and in India), parts of the market have come together to try to drive some level of consistency.

The International Capital Market Association’s (ICMA) Green Bond Principles offers best practice guidelines, which deliberately steer around the difficult issues of what exactly constitutes a green bond or how green it must be.

“The Green Bond Principles want to stay as suggested guidance, referring to external standards where appropriate,” said Hans Biemans, head of sustainability, markets at Rabobank in Utrecht. “The idea is to standardise, but not to limit the market, and certainly not to redefine certain assets where standards already exist. There’s no point defining a ‘green building’ or a ‘green car’ at this level of a financial instrument.”

But the 2016 edition of the Principles did include, for the first time, a section on external review, with a proposed template.

The Principles acknowledge four different versions of external review, offering subtly different levels of reinforcement and public credibility. The first is consultant review, which evaluates an issuer’s green bond framework, and the second is verification, which compares the framework to standards or claims made by the issuer, including external standards.

The third and fourth approaches are certification, which compares a green bond framework to an external and defined standard, and a rating, which opines directly on the greenness of a bond.

Process not gatekeeping

Most external reviews, of all four kinds, look at process, rather than green assets themselves, which is in part a function of the market’s structure.

“Our approach has given more emphasis to governance and process since the corporates came into the market,” says Christa Clapp, head of climate finance at Cicero in Oslo. “Development banks tend to have very clear processes… corporates tend to have less developed environmental governance systems, so we’ve focused more on the detail of their processes and whether they have the expertise to evaluate their environmental impact.”

In some cases, this is quite straightforward. Funding buildings assessed to a certain level of Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) or Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) standards for sustainability might be considered environmentally friendly. An issuer can set up a process which allocates the proceeds of a green bond to sustainable buildings, and a verifiable process based on a hard external standard exists.

For other projects, though, it is punishingly hard to come up with an objective assessment of environment virtue. How can a new-build solar power plant be balanced against a fleet of hybrid buses? Which is more green? Or are both acceptably green?

Green for whom?

It depends, of course, on what kind of investors are involved. Some investors buy green bonds explicitly to drive environmental improvements; others simply wish to do no harm or less harm.

“Investors want assurance they are going in the right direction,” says Flensbourg. “A dark green rating gives them lots of assurance; a light green suggests there are areas where they need engagement, guidance about where to start the dialogue with the issuer.”

Some investment firms need to provide detailed environmental reporting of their own, through to the end accounts which ultimately provide their capital; others may support the market, but without strong opinions about, for example, whether adaptation measures or new build renewable power offers a “better” environmental outcome.

“Our intention is to be a communication document, not necessarily to compare with other bonds,” says Vikram Puppala, manager, advisory and sustainability at Sustainalyitics in Toronto. “We don’t want to be the gatekeepers of green. Every investor has different criteria for what they consider green.”

Carry on verifying

There are, however, slow movements towards tighter standards — green verification which is based on impact assessments of the underlying assets, green reporting for the lifetime of deals, and more complex frameworks such as that of the Climate Bonds Standard.

Impact reporting, however, is a whole other frontier. Determining the carbon impact of a given project depends on assessing what went before it. So the impact of a new renewable power plant in Africa not only depends on what power output it produces and the life cycle of the plant, but also on how clean the energy sources it replaces were, demand for power and possible alternatives.

“The difficulty of comparing impacts gets to the heart of green bond philosophy,” says van den Tol. “For example, if you could get companies that operate in less sustainable industries to commit to a greener approach, that would probably make more of a difference to the planet than having the obvious green companies commit.”

Late last year, 11 SSA issuers agreed on a “harmonised framework for impact reporting”, aiming to iron out some of these issues, but it still leaves much up to the individual issuer and their advisors.

Corporates, however, have been less eager to make the leap to full-blown impact reporting. Many of them do, however, provide extensive sustainability reporting in their annual reports, which is picked over by the assurance firms (often, the same providers which also give green bond second opinions).

“Actually treasurers are often surprised, when they first look at doing a green bond, that there is already a lot of information being collected by the assurance companies themselves,” says van den Tol. “The assurance firms all verify the sustainability reporting in annual reports — it isn’t at all standardised, but it’s quite common to collect the information.”

Wrong approach

The voluntary nature of green bond reporting and reviewing seems deeply troubling to one steeped in the mind set of credit. Credit quality mostly doesn’t rely on the goodwill of an issuer, and a series of non-binding promises.

But that sort of scepticism misunderstands the point of the green bond market. Any issuer that has already got to the point of considering a green bond is unlikely to try to “game” its green status. Issuing a green bond does not save basis points, it enhances reputation — and a green bond whose standards fell short would take away more credibility than it conferred.

“The issuer is not getting cheaper financing from their green bond — they are only getting the credibility,” says Flensbourg. “If an issuer is found to be non-compliant, this credibility would not only disappear, it would turn negative.”

Furthermore, the point of that credibility is to demonstrate the extent to which treasury and environmental departments are connected to one another — to show that environmental decision-making is integrated in the core parts of the business.

“We actually advise issuers that if it’s not green, they should not call it a green bond,” says Puppala at Sustainalytics. “Issuers understand the point that it’s a reputation risk for them if they’re not fully aligned.”

Just because it is about creating symbols, rather than binding commitments, that does not mean green accreditation is false or unimportant. Changing organisational culture is crucially important to making environmental improvements, and tying powerful stakeholders like finance departments into the project is a quick way to bring that about.

“It’s far bigger than just assigning a carbon reduction figure — the market is about mobilising human capital, and connecting financial departments to sustainability,” says Flensbourg.

But it does mean that the green bond process — the part which is verified — is as important as the green bond itself?

My word is my bond

Proving greenness still largely relies on the issuers. Their processes can be assessed or endorsed by third parties, with varying degrees of independence, but it is still, ultimately, down to an issuer to make the right choice.

Some borrowers are apt to leave aside verification entirely. North American issuers show a particular tendency to do deals without it. Many of the issuers that do not bother are municipalities funding certain projects, or ABS issues backed by solar installations or home improvement programmes such as Pace (Property Assessed Clean Energy), which may not see the need for someone else to explain their environmental credentials to the market.

“We still think you need a second opinion even in pure play green sectors,” says Clapp at Cicero. “Projects such as hydro, for example, can be great from a carbon perspective but still have local environmental impact, while the supply chain for other renewable projects can also be something to pay attention to.”

That point of view is percolating slowly. External verification, as well as the underlying asset standards, are on a relentless march, even in the North American market.

“In five years’ time, I’d expect that external certifications on underlying assets will be much more common,” says Rabobank’s Biemans. “The world is working on all kinds of environmental certifications, which are not used yet in the green bond market, but certainly will be in the years to come.”

Certain verifiers or consultants might fall away, others will consolidate their grip on the market, and investors will, perhaps, demand more consistency from providers of verification.

“In the future, I’d expect to see more tiering of the external review market, with some players making market share gains at the expense of others, and some increased standardisation,” says BNPP’s Sfakianos.

That would surely be a good thing — right now, as befits a fairly new and effervescent market, there are a multitude of competing standards and recognised endorsements of various kinds, while both issuers and investors would surely prefer a stable oligopoly closer to the credit rating agencies. But this will not happen by accident.

“Green bonds are relatively new, take up has been huge, and there’s a growing demand which I don’t see going away,” says Fiona Reynolds, managing director of the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), a United Nations backed body that encourages environmental, social and governance (ESG) investments. “There are more and more serious investors in the market who have deeply held views about responsible investment, demand more from issuers, and be willing to pay for it.”

Institutions where the market can come together are essential to building a standardised approach to demonstrating and proving greenness, and to protecting the market from dilution. External reviews can only get better.