In the struggle to free itself from Chinese-dominated supply chains, the US government has turned to its rival’s own playbook — taking stakes in domestic companies. But investors and analysts are wondering whether this out-of-character behaviour by the US signals long term strategy or short-sighted panic buying.

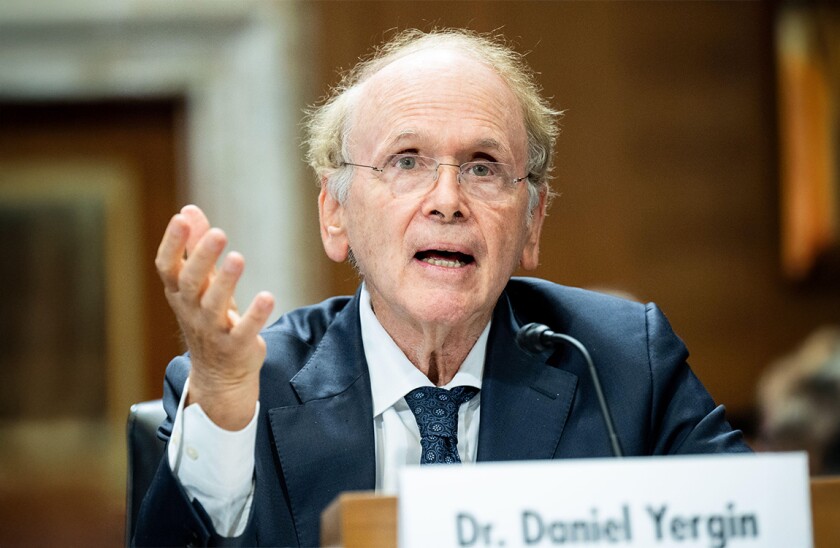

“It reminds me of Disraeli buying shares in the Suez Canal and Churchill buying shares in Anglo-Persian [Oil Co],” said Daniel Yergin, vice-chair of S&P (pictured), at the Institute of International Finance this week. “This is new territory.”

In July, the US government became the largest shareholder in rare earth producer MP Materials, part of a landmark public-private partnership to expand its production of magnets used in electric vehicles, robotics and defence. The following month, the government paid $8.9bn for a 10% stake in struggling chipmaker Intel.

President Trump’s description of his meeting with Intel CEO Lip-Bu Tan suggests more such arrangements on the horizon: “He walked in wanting to keep his job and he ended up giving us $10bn for the United States, so we picked up $10bn, and we do a lot of deals like that. I’ll do more of them.”

Plan unclear

Calls for a coordinated US industrial policy that teams with allies to create new critical mineral supply chains have been growing for years. But it remains unclear whether these equity stakes are the first steps in such a coordinated strategy.

The question, said Clay Lowery, IIF executive vice-president, is: “Does the US know what it’s doing?”

Reception of the two acquisitions has been very different. Even organisations traditionally friendly to Republican administrations balked at the Intel deal. The Cato Institute said it “marks a dangerous turn in American industrial policy.” Scott Lincicome, its vice-president of general economics, said Intel had been a “technological laggard“ for years, losing ground to competitors like Nvidia, AMD and TSMC.

“Adding a layer of political oversight to Intel’s already complex turnaround effort is far more likely to hinder than help,” he said.

The MP Materials deal has met more approval. “The MP investment was good opportunism,” said Emily Kilcrease, senior fellow at the Center for a New American Security. This is “a textbook case” where government investment and price support can help the production of critical materials that are challenging from an economic and environmental perspective, she added.

Yergin framed the move as “trying to send a message to the market” but said the key issue was the underlying economics of rare earth production. The US ranks second to last when it comes to development time for rare earth mines. “It takes 29 years to bring a major new mine [online], so there is a lead time problem here and a skill problem,” he said.

Equity stakes will do nothing to remedy either of these. “Trump coming in and taking 5% of a lithium company doesn’t mean that that project is going to get built faster,” said Chris Berry, president of battery metals-focussed research firm House Mountain Partners. “Nor does it mean that the project is going to ultimately be 100% successful.”

Ultimately, for the US to get its new interventionist industrial policy right, the people in government making the acquisitions will have to make very smart decisions. “We have yet to see if that’s the case,” said Sam Jaffe, principal at deep tech consulting firm 1019 Technologies. “The Chinese government has been very smart in the last decades in its position as a shepherd of large industrial companies and guiding them to an integrated industrial policy. If US bureaucrats can do the same, it has the chance to be something special. If it just turns into a political reward mechanism, it could end negatively.”