|

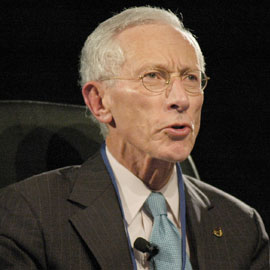

Stanley Fischer’s foresight in monetary policy has made him one of the world’s most respected central bank governors Stanley Fischer, central bank governor for Israel – a country with an economy about half the size of Ohio’s – will no doubt have an open door to US Treasury secretary Timothy Geithner and US Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke when he comes to Washington.

Fischer’s textbook example of pro-active monetary policy in the global crisis has buttressed his reputation as one of the world’s most respected economists and endeared him to policymakers globally. Fischer’s ahead-of-the-curve policy, both at the loose and tight phase of the monetary cycle, has been uniquely effective in recent years, says David Lubin, emerging market economist at Citigroup.

On August 25 last year, Fischer became the first central bank governor to hike interest rates as signs of a tentative global recovery emerged. The Bank of Israel hiked the policy rate this month to 2% to stabilize inflation, while the economy is set to grow by 3.2% this year.

Policymakers around the world have taken a keen interest in Israeli monetary policy, as Fischer’s influence transcends the nation’s $200 billion economy. The Zambian-born economist is a veteran fire fighter of economic crises as a former first deputy managing director at the IMF during the Asia, Latin America and Russian financial crises in the 1990s. This experience, combined with his grasp of economic theory, has equipped him with the instincts to spot both oncoming storms and emerging recoveries.

“I remember Michel Camdessus [the former managing director of the IMF] in the middle of Mexico’s 1994 crisis, saying ‘This is a crisis, and in a crisis, you do not panic’,” he tells Emerging Markets. “After observing crises in emerging markets, and from my experience teaching economics, I understand there is a clear rhythm to a crisis.”

In September 2008, as the western financial system imploded, Israel was shielded from the storm, as Fischer had already deployed his razor-sharp instincts and taken pre-emptive action. Between July 2007 and March 2008, as the US investment bank Bear Stearns began to falter, the central bank stepped up its acquisition of foreign currency reserves and snapped up long-term government debt.

When the global crisis erupted in September 2008, Israelis brought their money onshore, causing huge appreciation pressures on the currency. Thanks to the increase in the central bank’s firepower, with reserves rising from $28.5 billion to $61.2 billion between March 2008 and October 2009, it intervened to weaken the shekel. This ensured the export sector was not ravaged by an uncompetitive currency.

Fischer also blazed a trail by cutting Israel’s benchmark interest rate by half a percentage point on October 7, 2008 – a day before his counterparts in the US, UK and eurozone embarked on coordinated interest rate policy cuts to save the financial system from collapse.

Fischer then cut the rate to a record low of 0.5% by April 2009 and embarked on quantitative easing.

As a former chief economist at the World Bank and a member of the influential Group of Thirty, an economic policy think-tank, Fischer’s views carry global weight.

So how confident is he that the international financial system is on a stronger footing? “It is still an open question whether there has been the necessary adjustment in financial institutions, and whether there is sufficient international regulatory coordination,” he says.

As thesis adviser to a young Bernanke while teaching at MIT in the late 1970s, Fischer has a direct line to the world’s most powerful central banker to air these views.