Outflows from emerging market debt funds have been constant since May 2013, when US Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke first dared to utter the dreaded ‘tapering’ word. But that did not stop Mexico and Colombia, two of Latin America’s most prolific issuers, from printing blow-out transactions in September 2013 and then again in January 2014.

Mexico ended 2013 with an upgrade to BBB+ from ratings agency Standard & Poor’s and began 2014 in record-breaking style. The sovereign sold a $1bn seven year bond at 3.607% – its lowest ever yield for a dollar deal – and a $1.5bn 2045 note that grew to $3bn once existing bondholders had swapped into the new deal.

Two weeks later, Colombia managed its lowest ever yield for a 30 year – selling $2bn of 2044s at a yield of 5.647%. The level of demand allowed the nation to complete its funding for 2014.

|

These sovereigns were able to post record low borrowing costs in spite of an overall widening of their curves, and there is little evidence that LatAm sovereign debt is losing its attraction. NEW NAMES IN THE BOOK

DCM bankers, who worked on Colombia’s January deal, beam with pride as they say even US states and municipalities participated directly in the bond.

Michel Janna, general director of public credit and national treasury for Colombia, confirmed this, and says it is part of a broader trend of new kinds of investors looking at their bonds.

“Our last external bond was a very successful issue in which we began to see new types of investors, including sovereign wealth funds, buying our debt in the primary market for the first time,” he says. New institutional investors also bought the bond, he adds.

“If new buyers are coming into the LatAm sovereign market, it is very good news,” says Donato Guarino, a strategist at Barclays in New York. “Not only is it a diversification of buyers but also shows that the market is attractive on a relative value basis versus US investment grade.”

Brazil, in particular, is much wider than the equivalently rated credits in the US, says Guarino.

This is at least partly caused by negative projections on Brazil’s rating, with Standard & Poor’s placing the sovereign on negative outlook in June 2013 due to weaker fiscal performance and a greater government debt burden.

PRESSURE OFF

With spreads under “significant pressure”, according to Guarino, Brazil’s absence from the new issue market so far in 2014 has been notable. Yet Brazil has the advantage of not being obliged to issue. “Brazil performed liability management last year, and their goal is to use the external market to provide liquid benchmark points for corporate issuance,” says Guarino.

The sovereign’s 2025s and 2041 provide this, and indeed external debt remains less than 10% of Brazil’s total debt.

Therefore, even as the market remains mired in volatility, most investment grade sovereigns have not left themselves with the pressure of huge financing needs. The message is clear: Latin American countries – even those whose macroeconomic management may not earn plaudits from investors – have become smarter and more nimble issuers.

“In recent years, for the largest countries the international bond market has been all about liability management exercises,” says Alberto Ardura, head of Latin America capital markets and treasury solutions at Deutsche Bank in Argentina. “They have built out their yield curves and tried to replace the more illiquid bonds.”

As Ardura points out, the advantage of not having significant funding needs is that sovereigns have the “luxury” of waiting for the right moment – as Mexico and Colombia did in January.

POPULAR MEXICO

And even though Guarino admits he sees “potential pressure points” due to expected supply later in the year, as LatAm lags behind the rest of emerging markets in terms of sovereign issuance, the largest provider of supply is well liked among investors.

“Mexico has the largest supply requirements but can boast an improving credit story, with a recent upgrade and promising reform programme,” says Guarino. “The market should be there for them.”

Latin American investment grade issuers are “well positioned to weather the change in global liquidity thanks to their strong external buffers, flexible exchange rates, improved currency composition and the maturity profile of their government debt portfolios,” says ratings agency Fitch.

Away from Brazil, improving credit profiles are one of the factors that leave debt management heads at investment grade sovereigns calm in the face of rising base rates.

Colombia’s Michel Janna admits that tapering and the tightening of US monetary policy was one of the reasons the sovereign moved quickly to issue in 2014 and cover its entire financing needs for the year. However, Janna says, “As our debt over GDP is relatively low, the impact of increasing global interest rates is not a big concern for our fiscal accounts. The improvement of credit ratings and hence of the risk profile of Colombia mitigates this impact.”

Fitch and Standard & Poor’s both upgraded Colombia in 2013, while Moody’s placed the sovereign on positive outlook in July.

“Improving our rating is a top priority,” says Janna. “It is one of the reasons we introduced the fiscal law that mandates a reduction of the debt to GDP ratio.”

Colombia has increased its average debt maturity from six years in 2007 to nearly nine years today, according to Janna, while it is close to meeting its target of having 25% of its debt denominated in external currencies – versus more than half previously.

And Mexico became the second Latin American country, after Chile, to gain an A-handle rating in January, when Moody’s raised it to Aa3 on the back of a comprehensive set of reforms expected to increase investment in the country. If Fitch – which has the sovereign at BBB+ – eventually gives Mexico a second A rating as some bankers expect, more types of investor may become eligible to buy Mexican sovereign debt.

Meanwhile, Chile (Aa3/AA+/A+) and triple-B sovereigns Peru, Panamá and Uruguay are unlikely to need to tap the international markets at all in 2014.

SUPPLY PREDICTIONS DIFFERING

In spite of Guarino’s concerns, there is little consensus on supply levels. Fitch sees a decrease in LatAm external bond issuance to $17.3bn, citing “lower external amortisations, continued bond market development, increased non-resident participation in local markets and less benign international financing conditions.

But Barclays predicts an increase to $23.5bn, not including Venezuela or PDVSA. “The economic growth outlook remains weak, translating in lower tax revenues with consequent pressure on primary balances,” says Guarino.

Furthermore, he says, investment grade issuers have received a lift as US Treasuries have tightened, making the environment supportive for issuers in terms of overall cost of funding.

“Frankly, there is a perception that Treasuries are going to trade in a range over the next three to six months,” adds Guarino.

Deutsche’s Ardura sees “flat” levels of issuance year-on-year, expecting to see “the regular collection of new benchmarks in 10 and 30 year maturities to help corporate and sub-sovereign borrowers”.

IN BUSINESS, BUT FRAGILE

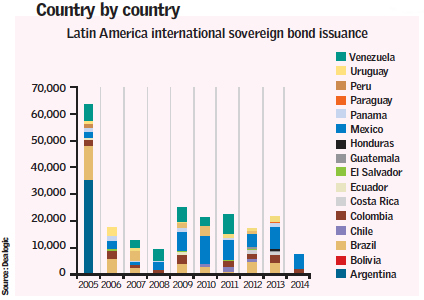

Dealogic data show that supply levels have been roughly stable in recent years. 2013’s volume of $22bn was higher than the previous three years – which were between $17bn and $18bn – but lower than 2009’s supply of more than $24bn.

Some of the increased volume in 2013 was due to high yield sovereigns taking advantage of exceedingly low borrowing costs, with the likes of Paraguay, Honduras and Dominican Republic all selling bonds.

This was a smart move, says Guarino of Barclays, as US Treasuries and EM spreads were at historically tight levels. “They knew that issuing $500m or more would include them in the EM benchmark indices that are tracked by large institutional investors, so it was cheap funding for them,” he says.

But Guarino believes many of those bonds were probably one-off opportunities, at least in the short term.

Deutsche Bank’s Ardura is “very optimistic that the market continues to be there for high yield sovereigns”, in spite of the lack of supply this year, but acknowledges these are not frequent borrowers.

There is evidence to suggest Ardura is right. Honduras, for example, had already sold a $500m 2024 debut bond at just 7.5% in March 2013, near the peak of the EM debt market, when it returned to bond markets in December that year.

By the end of the year the idyllic conditions for EM borrowers were history, and S&P had downgraded Honduras to B. But the Central American sovereign, led by Deutsche, was still able to sell a seven year at 8.7%.

In February 2014, Moody’s downgraded Honduras from B2 to B3, citing a widening fiscal deficit – which reached 7.7% in 2013 – and gross financing needs at more than 10% of GDP.

Honduras’ fragility is symptomatic of Central America, a region that – with the exception of Panamá – falls entirely in Latin America’s lower ratings bracket.

Most Central American economies have struggled to grow more than 2%–3% in recent years, which is a “concern” for Standard & Poor’s, said the rating agency in an update on Central America on March 12. Poor growth is holding back the ratings, said S&P, as it translates into lower government revenues and higher budget deficits.

And while Honduras tapped the market despite its problems, Barbados was not so lucky: the Caribbean island postponed a planned benchmark issue in October 2013, and “external financing challenges” was one of the drivers behind a two notch downgrade by S&P, to BB-, the following month

PARAGUAY EYES FREQUENT ISSUANCE

However, there are sub-investment grade sovereigns on the up. Moody’s upgraded Paraguay for the second time in a year in February – from Ba3 to Ba2 this time – and the country is aiming to achieve investment grade status in the “medium term”, according to finance minister Germán Rojas.

Paraguay is working “permanently with rating agencies and defining the actions needed to improve the rating”, says Rojas. S&P and Fitch both rate Paraguay BB-, with Fitch placing the borrower on positive outlook in January.

Moreover, the country may provide investors with the rare chance to pick up bonds of a new sovereign issuer on an upward trajectory. Paraguay has an investment plan of $16bn for 2014-18 and is contemplating an international issue of $1.5bn, according to the finance minister. “Our financing strategy includes using the international financial market in a permanent fashion in the next few years, and to become a frequent issuer,” says Rojas.

Rojas sees international markets as a way of raising long term financing for infrastructure projects, diversifying sources of financing, attracting large international investors into the country and facilitating debt issues for the private sector.

And as LatAm issuers reach new levels of sophistication, even Paraguay, which only issued its first dollar bond in 2013, is ready for the volatility – permanently monitoring the market and always ready for the best moment to issue, concludes Rojas.

- Follow us on twitter @emrgingmarkets